A Very Historically Blind Christmas III: The Epiphany of the Magi

In 1158, amid sieges by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, the embalmed corpses of three men were discovered beneath a church in Milan. One appeared to be that of a young man, another a middle-aged man, and the third, an old man, representing, as it were, the different stages of manhood. Because of their ages and how the idea corresponded with certain legends, these preserved remains were presumed to be the bodies of the Three Wise Men of the Christmas Nativity story and were thereafter hidden in a moat to prevent Frederick I from taking them, but take them he did, and gifted the relics to the Archbishop of Cologne, where they were purported to perform miracles and became the chief relics of the three most revered saints in Western Christianity, housed in the grand Shrine of the Three Kings. According to the 14th-century History of the Three Kings, the Three Wise Men of the Nativity story, also called the Three Kings and the Magi, agreed to be buried together at a certain hill on the border of India where their ways parted on their journey home after presenting their gifts to the Christ child, a place they called the Hill of Victory. How their remains ended up at Milan is another interesting tale, this one involving Flavia Julia Helena, later Saint Helena, the beautiful daughter of the fabled King Cole, or Coel the Old, in Roman Britain. Helena married Constantius and gave him a son, Constantine, who in 312 CE converted her to Christianity. In 325, she was said to have gone on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, where she discovered numerous important relics, including the hay from Christ’s manger, the nails used in his crucifixion, and even the True Cross itself. It was said that, after her pilgrimage to the Holy Land, she traveled to India, discovered the Hill of Victory, and brought the remains of the Three Wise Men back to Constantinople, where they remained until a bishop transported them to Milan sometime during a mid–4th-century period of Christian persecution in Constantinople. But there is much to doubt about this story, which was written centuries after the relics’ discovery in Milan. For example, it attributes their discovery to a much mythologized figure in St. Helena. First, her origin is suspect, with most scholars maintaining that she came from Asia Minor rather than from Britain, and that the figure of Old King Cole identified as her father may be entirely fictitious. Second, the idea that she discovered all the relics it is claimed she found in the Holy Land is hard enough to believe without her also mounting an expedition to India and finding a long-lost tomb like some ancient Indiana Jones. But also, the ages of the relics don’t make logical sense. They do indeed appear to be the remains of men aged around 15, 30, and 60 years, as modern science has confirmed by examination of skull sutures, but this would not make sense unless these Three Wise Men had died almost immediately after presenting their gifts, and all at the same time. The different sources comprising the legendarium that tells us their names—Melchior, Balthasar, and Caspar—do not agree on who came from which country: was Melchior or Balthasar a king of Arabia who presented a gift of gold? Was Caspar king of the Hindus or king of Tarsus? Was Balthasar actually king of Ethiopia and thus dark-skinned as he is often portrayed? Inconsistencies abound, but the legendarium is clear that all three lived past 100 years old, making the relics at Cologne problematic. But there are far more problems than these associated with this major element of the biblical Christmas story.

*

Before continuing to read, may I suggest you read my posts “Zoroaster, the First Magus” and “Gnostic Genesis” before listening to this episode. The former is perhaps the most important, as I discuss the historical magi, their beliefs and what was commonly believed about them, which provides essential background for much of this Christmas Special. The latter, while less essential, provides some useful background on what apocryphal writings are, which will come up along the way on our journey of the Magi. But to begin, rather than delving into the apocrypha from which much of the legend of the Three Kings derives, we must look to canon, and the only canonical scriptures that mention the visit of the Wise Men is the Gospel of Matthew, Chapter 2: “Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem, / Saying, Where is he that is born King of the Jews? for we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him.” Here in two verses, out of a passage of 12 verses only, we have the origin of a vast legendarium. Strange, then, that the other gospel featuring the Nativity, that of Luke, makes no mention of these visitors from the East. Moreover, the inclusion of the Wise Men in the actual nativity scene appears not to be supported by scriptures. I talked a great deal in my first Christmas special about confusion over the actual time of Christ’s birth, owing to Luke’s description of shepherds watching their flocks by night, and here we have a similar confusion. When Matthew’s wise men visit Herod, the king asks them “what time the star appeared” and after the wise men depart, he orders the Massacre of the Innocents, demanding the slaughter of all children “two years old and under,” which seems to indicate that the Wise Men first saw the star two years earlier. Yet the star that had signaled the birth of the King of the Jews appears to still remain overhead—another odd detail, for if this magnificent celestial sign had glared in the heavens above for so long, why was Herod so curiously unaware of it?—and it led the Three Kings not to a barn or a cave, as some versions have it, but to a “house” where they presented their gifts to a “young child” rather than an infant. So it seems some artistic license was taken to include the Wise Men at the actual nativity, and it seems further license has been taken all along the way as their legend grew. For example, how do we know they were kings, or that there were only three of them? This appears to have grown out of the mention of three gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh, and the fact that these were treasures befit for a king, which only other kings could afford to give. Then there is the connection to a prophecy in Isaiah that predicts “Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising” and that “they shall bring gold and incense.” But how much of this was speculation, how much folklore, how much a purposeful attempt to fulfill prophecy and further some other religious or political agenda?

A detail of the Three Wise Kings from the Atlas Catalan, 1375. Public Domain.

Certainly the visit of these Wise Men has become a touchstone in Western culture, its mythic standing resulting in its appearance in all kinds of art. Numerous masters have paintings that depict the adoration of the Magi, including Botticelli, Bruegel, and Hieronymus Bosch. They have been the subject of much poetry as well, with both William Butler Yeats and T.S. Eliot having penned memorable verses about them. And the Christmas carol, We Three Kings of Orient Are is not the only song to immortalize their legend. But their legendarium really begins in apocryphal texts, such as the protoevangelion, or infancy gospels, from the 2nd century CE. These dubious texts, which have been called “mythological trash” by some scholars, offer more details on the birth and early years of Christ. The gospel of pseudo-Matthew doesn’t have them adoring the Christ Child at birth, replacing the Wise Men with an ox and an ass that worship him instead, and this account seems to indicate even more clearly than the canonical Gospel of Matthew that the Magi had seen the star rising in the east two years before making their trip and thus found Jesus as a small child in a house. However, the Infancy Gospel of James places the Wise Men more specifically at the scene of the Nativity, describing how the Wise Men were led by the star to a cave, rather than a barn. An Armenian Infancy Gospel, some centuries later during the late 6th century CE would number them three, give them their names, and make of them kings from specific places. After that, much of their mythology first appeared in medieval romances, which themselves tied the Wise Men to already dubious apocryphal legends, such as the detail that they were baptized in India by Thomas the Apostle during his travels on the Indian subcontinent, even though the only work to describe these travels, the apocryphal Acts of Thomas, makes no mention of them. Further, it was alleged that one of the Three Kings was a forefather of Prester John, a legendary Christian king in India that most scholars believe was a fabricated character of medieval fantasy. And perhaps one final legend shall suffice to demonstrate how entangled the story of the Three Wise Men is with myth and folklore: that of La Befana, the Christmas Witch. In Italian folklore, Befana was an old woman whom the Wise Men passed by on their journey. She asked the travelers where they were headed, and the Wise Men told her about the star they followed and the newborn king to whom it would lead them, and they invited her to join them. However, La Befana was far too busy sweeping and declined to accompany the Wise Men. Later, when she realized that she had lost an opportunity to worship the redeemer that the world had been waiting for, her bitter regret kept her alive to wander around Italy, rewarding the good children by leaving gifts and candy in the socks they hung to dry by their hearths, and leaving only garlic, onions, and coal in the socks of children who had been less than well-behaved. Clearly this legend is all twisted up with other Christmas folklore that I have discussed previously, but La Befana visits children after Christmas, during Epiphany, the Christian holiday celebrating the Three Wise Men and the revelation of Christ as the incarnation of God. Indeed, the witch’s name, La Befana, is even derived from the word Epiphany.

So enmeshed in myth and legend is the story of the Wise Men that in order to find some solid ground from which to start an investigation into their identities, many have looked not to them but to the object their fascination, the Star of Bethlehem, which as a celestial event at least seems approachable through science. Because of its description as an unusual sight which remained for so long, at least throughout the entire months-long journey of the Wise Men, if not for the implied 2 years, rather than a star per se, many interpret it to have been an astronomical event. A fireball or meteor would seem to fit the bill, but as that would disappear within moments, we must look for other phenomena. A supernova has been suggested as another likely candidate, as supernovas can be visible for years and in early records were mistaken for stars, even called a “guest star,” but the earliest record of a supernova was recorded by the Chinese in 185 CE. It seems unlikely that only the Gospel of Matthew, written some 75 to 100 years after the events described, would provide the only record in all cultures of such a bright and easily visible natural event. And this fact casts doubt on the entire notion that this astronomical event occurred for two years. As for events that might have lasted for months, a comet could provide an explanation. However, unlike supernovas, comets were more commonly observed in that era, and were typically seen as the finger of a god, a portent of calamity rather than as a sign of a coming king among a certain people or in a certain place. Then we have the description in Matthew, after the Wise Men meet with Herod, that the star “went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was.” This certainly does not behave as one would expect a comet to behave, and so it makes sense that many Christians view the Star of Bethlehem more as a miracle than an astronomical event—something more like the pillar of fire illuminating the Israelites’ night journey out of Egypt in Exodus. To a modern reader, it may sound more like a UFO, and interestingly, there are many parallels between depictions of UFOs today and angels in the past, both appearing as lights in the sky.

The Adoration of the Magi by Bartholomäus Zeitblom, c. 1460. Public Domain.

Interestingly, at least one apocryphal text, the Infancy Gospel of James, seems to confirm the idea that the star was actually an angel, for after their visit with the Christ Child, it says they were “warned by the angel not to go into Judea,” according to the “Scholars Version” translation using the definite article “the angel,” when the Wise Men had not earlier been shown to be in contact with an angel but rather being led by the star, giving the impression that the star had been an angel all along. However, The Infancy Gospel of James also employs different wording, making it seem like the star did not move before them and stand over the place where Christ was: “Then, the star which they had seen in the east led them until they came to the cave and stood over the head of the child.” Here we see that it was the Wise men themselves who stood over the child’s head… and one cannot help but wonder if that is what the Canonical Gospel meant to say, a slight distinction, a confusion of subject and verb, lost in awkward phrasing and translation, that makes an important difference. But then again, as mentioned, the Infancy Gospels are not the most reliable of sources. Among the novel embroideries of the Infancy Gospel of James, we see Mary being fed by angels as a child, and rather than delivering the Christ Child by any normal means, there is a flash of light and Jesus simply appears at her breast. Then there is the strange cameo of Salome, granddaughter of Herod, who appears in the Nativity scene here despite her being described in Mark as being youthful when Jesus was an adult. Intrigued by the story of a virgin birth, Salome wants to see for herself, but when she inserts her finger into Mary to determine if her hymen is intact, her hand is “consumed in fire.” Only holding the Christ Child restores her hand to her. All this to demonstrate that the Infancy Gospel of James may indeed be the “mythological trash” that scholars have said it is, making it unreliable as evidence for what the Star of Bethlehem was or how it led the Wise Men to the Christ Child. But, then again, is it any less unbelievable than other wonder-filled books of the Bible that have been established as canon?

For a more rational interpretation of the Star of Bethlehem, we must consider why these Wise Men are sometimes called the Magi. The original Greek word used in the Gospel of Matthew that has been translated as “wise men” was mágoi (μάγοι), a seemingly direct identification of these men from the east as followers of the ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism. It is curious that the term magi would be translated as “wise men” since the magi were largely seen as practitioners of evil magic. Even elsewhere in the Bible, the term is applied, in its singular form, to the most wicked sorcerer of all, the originator of all heresies, Simon Magus. However, it may be that the word was simply being used by Matthew to indicate that the men were astrologers, for Zoroastrian magi were widely credited as the inventors of astrology. And here we find an interesting explanation for the Christmas Star. As astrologers search for portents in the stars and alignments of planets, perhaps this is what led the Wise Men to Bethlehem. In fact, a few noteworthy planetary alignments have been suggested by astronomers as possible candidates. Keep in mind that the exact year of Christ’s birth has never been determined with any certainty, and he likely was not born at the end of the year 1 B.C. as the former calendrical reckoning of “Before Christ” would imply (evidence of which, having to do with the known dates of King Herod’s life and reign, I discussed in my first Christmas special). So if we are not tied to that date, we can see a triple conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 7 BCE that may have inspired astrologers to make a journey to the land of the Hebrews. Three times that year, Jupiter, a planet representing royalty, passed before Saturn, a planet seen as a protector of eastern Mediterranean peoples, and this took place within the astrological sign of Pisces the Fishes, which to many eastern astrologers meant a portent for the Hebrew people. If that didn’t fit the bill, another possibility exists.

The Journey of the Three Kings (1825) by Leopold Kupelwieser. Public Domain.

In 3 BCE, a number of curious planetary alignments occurred. In August that year, while Venus and Jupiter were in conjunction, Mercury and the Sun and Moon were in the sign of Leo the Lion, a sign associated with the Jewish tribe of Judah. Then the next month, Mercury aligned with Venus and the Sun entered the sign of Virgo the Maiden. Considering that a prophecy foretold of a virgin birth in the House of Judah resulting in a savior, these planetary movements may have been interpreted as confirming the prophecy’s imminent fulfillment. After that, Jupiter aligned with the brightest star in Leo, Regulus, and would pass it again two more times in the next year, 2 BCE. Then, in June of that year, exactly 2 years from the summer of 1 CE, when, it should be remembered, it was more likely for shepherds to be watching their flocks by night as described in one version of the Nativity, a spectacular “double planet” conjunction of Jupiter and Venus occurred that would have been unlike anything astrologers of the day had ever seen. Indeed, we did not see a similar occurrence for another 2000 years, in 2016. A similar “double planet” conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn on the 21st of December this year is likewise being hailed as a “Christmas Star.” Before we say case closed and declare that Matthew was certainly referring to these conjunctions, though, it must be pointed out how strange it is that, considering the astronomical knowledge of the day, Matthew used the word for star rather than referring to the event as a conjunction of planets, and Herod and his court, who would have been familiar with astrology, had no idea about this conjunction. Moreover, a conjunction of planets would not explain how the star appeared to move as it led the Wise Men, or how it stopped over the place where the Christ Child was. And perhaps most strange is that Matthew would indicate by this passage the efficacy of astrology, a forbidden practice and belief considered to be false and against God.

Now we get to the heart of the matter. Who was this Matthew who wrote the only canonical Gospel that mentions these Magi from the east who followed a star to Jesus, and what can the historical and geographical context in which it was written tell us about why this singular passage appears? Little is known about the author of this gospel, but it can be discerned that he was a speaker of Greek, and a Jew who had converted to Christianity. He is believed to have written the document in Antioch, sometime between 80 and 90 CE, almost a hundred years after the events he is recording. Antioch was connected via some nearby major commercial roads to cities like Edessa and Hierapolis, which had inherited much from ancient Persian and thereafter Parthian cultures, including thriving Zoroastrian traditions. Indeed, as a center for education, Antioch received eager-to-learn young people from these other cities, who brought with them Zoroastrian beliefs. As such, Antioch was a multi-cultural milieu where syncretistic beliefs began to sprout up and where astrology was popular. As such, it is perhaps no surprise that Matthew incorporated astrologer Magi into his version of the Nativity. Indeed, it may have represented an effort at syncretism, an attempt to reconcile Christianity with the practice of astrology, for if astrology had successfully predicted the birth of the Messiah, it couldn’t be all bad, right? But more than this, the very notion that Magi, or priests of the Zoroastrian faith, would recognize Jesus as the foretold savior is a syncretism of Christianity and Zoroastrianism, for as I discussed in my previous post on the topic, Zoroastrians too believed in the coming of a savior figure who would be born to a virgin mother.

The Adoration of the Three Kings, anonymous. Public Domain.

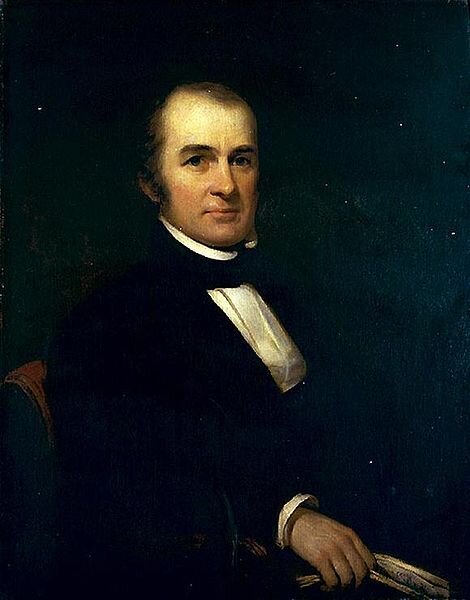

Another possibility may be that, rather than trying to co-opt Zoroastrianism, Matthew may have been inventing details in order to make it seem as though Christ’s birth represented the fulfillment of known prophecy. First, there is the prophecy of the wicked Gentile diviner Balaam in Numbers Chapter 24, which states that “there shall come a Star our of Jacob, and a Sceptre shall rise out of Israel.” Interestingly, some early Christian writers viewed Balaam as an astrologer and even sometimes suggested he was Zoroaster himself. Then there is the prophecy from the Book of Isaiah, Chapter 60, which indicates that “Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising” and mentions specifically their arrival on camels and gifts of gold and incense. Some writers, including Catholic scholar Dwight Longeneker, who has written a whole book about the topic, use this verse of prophecy to try and narrow down who the Magi were. Based on these verses mentioning that Gentiles would come from such places as Midian, Ephah, and Sheba, he argues that they were not Persian Zoroastrians but rather astrologers from the neighboring kingdoms of Nabatea and Sheba, and that the word magi was a common misnomer for any astrologers. To support his claim, he argues that these Kingdoms were linked to the kingdom of Herod by a trade route, on which they traveled to sell incense and myrrh, made from resinous plants native to their lands. This is all rather convincing, but only if you believe that what Matthew wrote had to be true, when in fact, he was likely aware of these prophecies and working them into his account. His inclusion of the brief story of the Wise men recalls both Balaam the Gentile astrologer’s metaphor of a King in Israel as a rising star AND the notion of Gentiles coming from afar to offer gifts specifically of gold and incense. So what is more likely, that this one version of the Nativity, written almost a hundred years later, with details not corroborated by contemporary sources, proves these prophecies accurate, or simply that these prophecies served as Matthew’s source material?

As we consider what may have driven Matthew to invent the story of the Wise Men and the Star of Bethlehem, yet further agendas present themselves. In emphasizing that wise Gentiles recognized Christ as the Messiah, perhaps he was not trying to validate astrology so much as he was trying to present a negative view of the Jews, who were not as accepting of Christ’s divinity. Certainly this has been one reading of the story. Or, there is the idea that, rather than validating astrology or co-opting Zoroastrianism, the story of the Star of Bethlehem was intended as a repudiation of those beliefs. After all, early Christian literature sometimes described the Star as being brighter than anything else in the sky, causing all other heavenly bodies to be dim. By this reading, the Star represented Christianity rising victorious over Zoroastrianism and astrology, a symbol of God’s destruction of magic. Lastly, it is also possible that there was a more political motivation behind the story. The arrival of Persian magi who sought to give respect not to Herod but rather to a new king appears to represent the Persian or later the Parthian rebellion against Roman rule, which the Jews had long associated with liberation. The Persian king Cyrus had previously liberated the Jews from Babylonian captivity, so during the Roman occupation of Judea, many looked again to the enemies of their enemies, the inheritors of the Persian Empire, the Parthians, for a second liberation. By this reading, Matthew’s Gospel is revolutionary literature. What all of these interpretations have in common is that they view the passage concerning the Magi not as fact but as metaphor, which of course would make all the subsequent mythologizing of their characters nothing but fantasy. It seems this figurative interpretation of scripture was actually rather common among early Christians. It is very odd, then, that today, after the Scientific Revolution and Age of Enlightenment, so many still insist on an absolute, literal reading of the Bible.

The Adoration of the Magi by Matthias Stom. Public Domain.

Further Reading

Bakich, Michael E. “What Was the Star of Bethlehem?” Astronomy, vol. 38, no. 1, Jan. 2010, pp. 34–39. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=45390790&site=ehost-live.

Estakhr, Mehdi. "The Journey of the Magi: Its Religious and Political Context." World History Bulletin, vol. 32, no. 1, Spring 2016, p. 24+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A603404338/GPS?u=modestojc_main&sid=GPS&xid=59f778a1.

Grigson, Geoffrey. “The Three Kings of Cologne.” History Today, vol. 41, no. 12, Dec. 1991, pp. 28–34. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=9112233542&site=ehost-live.

Hegedus, Tim. “The Magi and the Star in the Gospel of Matthew and Early Christian Tradition.” Laval théologique et philosophique, vol. 59, no. 1, Feb. 2003, pp. 81-95. Érudit, www.erudit.org/en/journals/ltp/2003-v59-n1-ltp477/000790ar/.

Longenecker, Dwight. “Who Were the THREE WISE MEN?” Catholic Digest, vol. 82, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 52–55. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=127134763&site=ehost-live.

---. “‘We Three Kings’. (Cover Story).” Catholic Answer, vol. 28, no. 5, Nov. 2014, pp. 15–17. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=98513445&site=ehost-live.

![Tiebout, Cornelius, Engraver, and Rembrandt Peale. Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States. [Philada. Philadelphia: Published by A. Day, No. 38 Chesnut Street, Philada., ?] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d0686e6b8f5b98e0543620/1606717713969-QJ3XT1V293D6G6K63459/image-asset.jpeg)