Zoroaster, the First Magus

Circa 77 CE, the great natural philosopher Pliny the Elder published the first 10 volumes of his encyclopedic masterwork, Naturalis Historia, or Natural History, a work with a scope no less grand than that of all Creation, to record all knowledge of everything. In it, between lengthy treatises on all known arts and technology, he writes witheringly of “the most deceptive of all known arts, [which] has exercised the greatest influence in every country and in nearly every age.” This sinister practice he calls “the magic art,” and he goes on to reveal “when and where the art of magic originated [and] by what persons it was first practised.” According to this renowned encyclopedist, “There is no doubt that this art originated in Persia, under Zoroaster, this being a point upon which authors are generally agreed.” But who was this Zoroaster, or Zarathustra as the Persians called him? A simple wise man as Friedrich Nietschze would eventually characterize him? A holy man who brought the true god’s faith to humanity, as Zoroastrian scriptures remember him? Or a sorcerer whose elite class of priestly adepts spread his magical craft across the world?

*

In this episode, we begin another ongoing series, in which I invite you peer into the darkness of Western esotericism and its many strange stories. We begin with Zarathustra and the priesthood of supposed sorcerers that followed his teachings, the Magi of Zoroastrianism, because of the claim that the practice of magic originated with them. Certainly we know that the word “magic” is derived from the Latinized ancient Greek word for them, as is the term “mage,” synonymous with wizard, taken from the singular for one of these Zoroastrian priests, a “magus.” Now you may recognize this word specifically from the nativity story celebrated every Christmas, as part and parcel of that legend is the story of the Three Kings or wise men, also referred to as Magi, who followed a star to witness the birth of Christ. I may save my examination of that particular legend for this year’s Christmas Special, but it illustrates clearly the notion that these figures were respected in ancient Greece as bearers of uncommon wisdom. More than that, though, the Magi were seen, at least by the time of the Roman Empire when Pliny the Elder wrote of them, as the founders of an insidious tradition of sorcery. In this series, I want to look at the many and various stories throughout history about the occult and the arcane, about alchemy and theurgy and necromancy, about secret societies and spellbooks. I hope you enjoy the first volume of my Encyclopedia Grimoria, in which, counterintuitively, I begin with an entry under Z, for Zoroaster, the First Magus.

The most famous of the magi: the three wise men who adored the Christ child, via Wikimedia Commons

*

Before we undertake a history of magic, it proves necessary to provide a definition of the word. In its original sense, magic would mean the wisdom of the Magi. That definition is useful to the discussion at hand, but proves inadequate when considering the wider history of magic. And defining magic is no easy task; it has been widely debated among anthropologists and historians, with the final result that it is more and more viewed as a useless or meaningless term inappropriate as a descriptor in scholarly works, and the very act of defining it has been called “maddening” by one of those scholars, Owen Davies, who has written much on the subject. It’s argued that the term “magic” brings with it many cultural connotations that may not be applicable in every case. For example, in its Western usage, the term conveys a sense of otherness or transgression, indicating practices outside of social norms or acceptable boundaries, when that may not always be the case. Likewise, a sense that the practitioners of magic might be considered primitive because of assumptions about the term, and the implication that they might actually be capable of producing supernatural effects when they are not and would not themselves consider their practices out of the ordinary, all have led most scholars to abandon the term. But I will endeavor here to walk that tightrope in order to clarify my use of the term. First, I differentiate magic from the art of illusion, meaning the performance of illusions for the purposes of entertainment, as observed on Las Vegas stages and at children’s birthday parties. Second, I would clarify that, much that has been called magic in the past is recognized today as medical or physical science. However, its explanation today does not preclude it’s being considered a magical practice in the past. The first criteria for considering any practice magical would be that it ostensibly seeks by some obscure means--whether that be through something as acceptable to the modern mind as chemistry or something as anathema to rational thought as spellcraft--to uncannily influence, manipulate, exert power over, or gain a preternatural understanding of the natural world. The second working criteria would be that, due to the very obscurity of these means, and/or their uncanny effects, the practice at least appears to partake of the supernatural. This definition, one might acutely discern, does not rule out frauds, provided they purport to be accomplishing some magical effect over the natural world through appropriately arcane practices.

With this working definition in hand, we can already see that magic in some form preceded the Magi, for beyond the term “magic” the ancient Greeks had further words to denote such activities, such as nekuomanteia, or necromancy, referring to communication with the dead, and pharmaka, from which we derive the word pharmacy, which in antiquity also meant the preparation and use of drugs, but also poisons, with the implication of what modern fiction would call potions. Another ancient Greek word for a magical art was goēteía. This word seems to have been used to refer to sorcerers, but it may have derived from the sound its practitioners made, a low wailing, which has led some to believe that the term referred to ritual mourners bemoaning the dead. There is much written about goētic magic asserting that it is the practice of summoning demons to answer questions or do the magician’s bidding, putting it at the other end of the spectrum from another magical art called theurgy, which summons beings less dark for much the same reasons. According to the lore that has grown up around the term, goētic arts were developed not by mankind but by a mythical race, the Dactyls, who also invented metallurgy and founded the Olympic games. Nor was this the only version of history suggesting that magic, rather than originating from Zoroaster, was given to mankind by another race of beings. For example, one text appeared in the 4th century CE, attributed variously to Clement of Alexandria or Bishop Clement of Rome, who would become Pope Clement I, which claimed that fallen angels had taught humanity magic. This corroborated another apocryphal text from a century earlier, The Apocalypse of Enoch, which tells of these fallen angels’ dalliances with human women, essentially the story of the Nephilim from Genesis 6, with the further addition that these so-called Watchers tutored their consorts in sorcery. However, these tales arrived far later in history and were spread through books of dubious reliability written by authors that took false names. This we will find to be a typical hurdle in critically evaluating the history of magic; much of its provenance is problematic, with entire traditions about ancient history based on spurious claims asserted by anonymous authors centuries and sometimes even millennia later.

Illustration of angels being cast out of heaven, via Wikimedia Commons

The same is true even of the association of the term Magus or Magi with Zoroastrianism, which was a prominent religion in Persia long before it was associated with magicians in Greece. When the term Magi is first seen in ancient Greek texts, it is not in reference to the followers of Zoroaster. The magi were certainly considered crafty and alien, their rituals strange, but their clear identification with the Persian traditions promulgated by Zarathustra did not happen until the 4th century BCE. Before that, Zoroastrians were depicted more as fire worshipers than conjurers or spellcasters, and the Magi were decried for their human sacrifices and their incest, none of which are related to Zoroastrian belief or ritual. In fact, another point against them was the way they sang in suspiciously low voices, which seems to suggest that these Magi were actually practicing goēteía, the “howling art.” Could these have been two very different cultural practices, perhaps both foreign to ancient Greeks and therefore confused for each other? Certainly by the Roman era, all the other words for magical practices like goëtia, necromantia, etc., were routinely folded into the term magia, so some conflation or syncretism seems likely. The result is that today our universal term for all sorcerous arts remains the word “magic.”

What we can say with some certainty is that certain magical arts attributed to Zoroaster could not have been invented by him. I am speaking now of the practice of astrology, which today we might not think of as magic but which was certainly considered magical in antiquity, and by my definition may still be considered a magical art, whether or not you believe it to be bogus. Astrology is one of the magical arts specifically ascribed to Zoroaster by Pliny the Elder, and indeed, the name Zoroaster even means “star-priest” or “star-diviner,” which appears to describe an astrologer. However, to credit him with inventing the zodiac and the art of divining the future based on the stars, one has to rely on a problematic timeline. The oldest archeological evidence we have of the practice of astrology appears to be from the 3rd millennium BCE in ancient Mesopotamia. More specifically, these were lists of omens in the sky and astral predictions compiled for Akkadian and Sumerian kings. Ancient Mesopotamia may have encompassed or at least abutted the region from which it is said Zarathustra came, but all accounts point to him being born many years later, which would seem to disprove at least the claim that he invented this one magical art. You see, Zoroastrian tradition holds that their central prophet was born in the 6th century BCE, some two millennia after the first known use of astrology in Mesopotamia, and his original Persian name, Zarathustra, had nothing to do with the stars and everything to do with a practical, earthly profession, its meaning having something to do with handling or caring for camels. His placement in the 6th century BCE derives from numerous texts indicating that, for example, there were 258 years between his appearance and the age of Alexander the Great, or that he was known to have met with and taught Pythagoras, who lived from around 570 to 490 BCE. However, many scholars cast doubt on this timeline, suggesting it was invented by Magi looking to cement their prophet in a historical context like Christ, or that it was a fabrication of Greek thinkers who wanted to minimize the claims that Greek philosophy was derivative of Eastern philosophy. For example, there are numerous earlier claims that Plato was influenced by the teachings of the Magi, and that Zoroaster had lived some 6000 years before Plato. Plutarch agrees with this placement of Zoroaster in the far reaches of prehistory when he declares that Zoroaster lived 5000 years before the Fall of Troy. If this were the case, then one supposes he could have invented astrology, but through linguistic analysis of the language used in the Avesta, the oldest of Zoroastrian scriptures, modern scholars propose that Zarathustra lived sometime between 1200 and 900 BCE, once again making him far younger than the art of astrology.

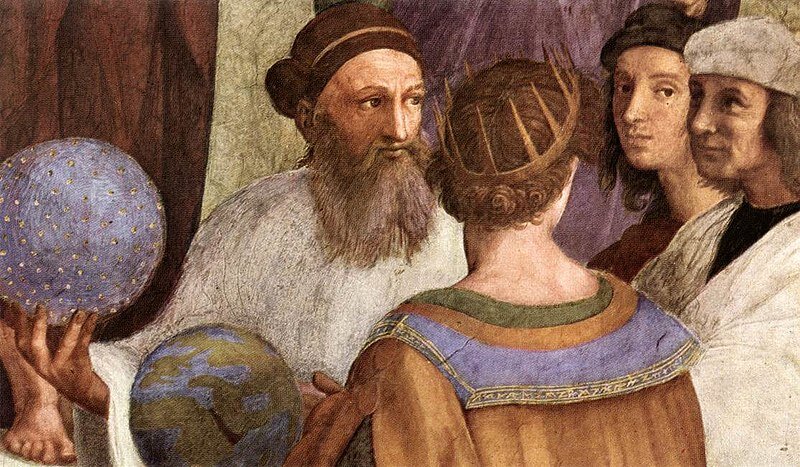

Zoroaster depicted sharing astronomical or astrological knowledge in “The School of Athens",” via Wikimedia Commons

Many of the passages in ancient Greek texts that mention Zoroaster further confuse matters by indicating he came from Bactria in Eastern Iran or Media in Western Iran, or referring to him not as a Persian, but as Zoroaster the Chaldaean or Zoroaster the Assyrian. This has led to speculation, since the name Zoroaster or Zarathustra or something similar was likely popular among adherents, that perhaps some of the Zoroasters recorded by Greek writers were different men living in different times and places. Indeed, even Pliny the Elder concedes that “whether there was only one Zoroaster, or whether in later times there was a second person of that name, is a matter which still remains undecided.” Then there is the further problem of Christian writers in antiquity identifying him with biblical figures, arguing variously that Zoroaster was the same person as Adam and Eve’s descendant Jared, or Noah’s cursed son Ham, or Ham’s grandson, the king, Nimrod, or the Babylonian prophet Ezekiel, all of whom lived in different times and places. To clarify, then, we must return to the Zoroastrian scriptures, to the Avesta, or more specifically the oldest portions of it, in the Yasna, which includes a series of hymns said to have been written by Zarathustra himself, called the Gathas. As the author of these Gathic texts, Zarathustra is the founding figure who brought this religion to mankind. However, scholars have pointed out that since different points-of-view are used throughout, sometimes first-person and sometimes third, the Gathas should be considered the product of an oral tradition to which many priestly figures like Zarathustra may have contributed. Nevertheless, when the Gathas mention Zarathustra, they accord him the role of forerunner, the first proponent of the faith, so Zoroastrians, like Christians, have come to think of him as a prophet or messenger, bringing to mankind the words authored by their conception of god, a being named Ahura Mazda.

Zoroastrianism presents a clearly defined cosmogony, or theory of the universe, complete with a detailed eschatology, or end times and afterlife scenario. According to the teachings of its scriptures, all of reality is divided in a dualistic conflict between two principles, characterized as good and evil, life and death, light and darkness, illness and health, order and chaos. These principles are embodied in two spirits, the omniscient god Ahura Mazda and its dark and evil counterpart, Angra Manyu. The conflict between these two deities led to the creation of the world of living beings, our world, which has an expiration date. It would only last 12 millennia, during which time the conflict between Ahura Mazda and Angra Manyu would play out here, among the divine sustainers of order and the demonic agents of chaos, and among the mortal men and women who were created thereafter. Upon death, these mortals’ souls would be subject to judgment, weighing their good and evil thoughts and thereby deciding whether, when they crossed to the afterlife, the bridge they took would grow as wide as it was long and lead them to the “best existence,” or whether it would narrow to a razor’s edge and cast them into a place of torture. The souls thus damned would only be redeemed at the end of the world, when after an apocalyptic age of disasters, the dead are raised and the dragon of the heavens sets the earth ablaze, purifying mankind.

Now, if some of this sounds familiar to you, that’s because it is very similar to numerous later traditions. Indeed, there appears to have been extensive borrowing from Zoroastrian belief systems in the establishment of other religions. For example, the Roman mystery religion of Mithraism took its central figure from Zoroastrian myth, as Mithra was one of Ahura Mazda’s divine figures on Earth. And many have looked to the Zoroastrian dualistic conception of coequal spiritual forces as the origin of other dualistic cosmogonies that see good in the spiritual and evil in the material, such as Manichaeism and Gnosticism. The similarities abound when it comes to Judeo-Christian traditions. Beyond the obvious parallels--the creation myth, the resurrection of the dead at the end of the world, and the judgment of their souls before being granted entry to paradise or being consigned to hell--there are even further connections. Mankind originates from a first man, like an Adam, Gaya Maretan, whose descendant, Yima, is directed by Ahura Mazda to preserve different forms of life in a bunker during the cataclysmic floods Mazda sends, much like a Noah. Even the figure of a savior prophet like Christ is present, in that Zarathustra imparts to all mankind the true revelation of God, thereby kicking off the final three millennia before the end of the world, and like Christ, he would return. In Zarathustra’s case, he will return three times, at intervals of a thousand years. His return will be in the form of a son born miraculously every thousand years to a virgin who bathes in a sacred lake that has preserved his semen. Each of these sons will act as a “Revitalizer,” the third and final son helping to bring mankind toward the “Perfectioning” at the end of all things. All of which, while fundamentally spiritual and in places decidedly mythic, gives no indication of the practice of ritual magic among the religion’s adherents.

Why, then, is Pliny the Elder so adamant in naming Zoroaster as the originator of magic? In the way of sources, he names one Ostanes, a supposed sorcerer who accompanied the Persian king Xerxes during his invasion of Greece, as “he who first disseminated, as it were, the germs of this monstrous art, and tainted therewith all parts of the world.” The problem is there doesn’t appear to be any surviving historical evidence of this person having ever actually existed, let alone writing major works on magic that Pliny says were “still in existence.” So we look to the principal source that Pliny cites on all things magical, Democritus, a contemporary of Socrates who Pliny states developed the art of magic through his writings during the time of the Peloponnesian War. Since many lost writings are preserved only in other writings that reference them, we may assume that Pliny’s understanding of the lost magical writings of Ostanes came from the magical works of Democritus. And here we begin to see the central obstacle to tracing the origin of magic to the Zoroastrian Magi. These works about magic attributed to Democritus do exist, but they are believed to have been written by someone else, an Egyptian by the name of Bolus of Mendes who lived some two centuries after the real Democritus. It is thought that Bolus attributed his work to Democritus specifically because of his association with Pythagoras, who, if you recall, was said to have studied under the Magi. Thus, Democritus would have a better claim to magical knowledge. This is typical of Hellenistic thought, which believed true wisdom and esoteric knowledge predated the Greek philosophers and had come from the East. Thus, numerous works on magic also appeared during the Hellenistic period that were attributed to Ostanes and even to Zoroaster himself, all of which have been definitively proven to be pseudepigrapha, or works spuriously attributed to famous figures in order to lend them an authority they might not otherwise have.

In 1938, French scholars Joseph Bidez and Franz Cumont published their seminal work on the subject of Zoroastrian pseudepigrapha, The Hellenic Magi, presenting in exhaustive detail all known texts and fragments and asserting that their contents do not correspond with Zoroastrianism, proving their false attribution. However, citing certain elements of the texts that did seem authentically Persian in origin, they argued that they had been written by “Maguseans,” authors with Zoroastrian beliefs who lived in the Roman empire at such a geographical and chronological remove from the heart of Zoroastrian belief that they had developed an unorthodox form of the religion. However, this conclusion has been challenged as recently as 2006 by a Quack… that is, by a German Egyptologist with the unfortunate name of Joachim Friedrich Quack. Building on theories that were put forward as early as the 1960s, Quack goes through example after example to show how works by pseudo-Zoroaster on herbalism, amulets, and astrology and works by pseudo-Ostanes on demonology and alchemy all show decidedly Egyptian influence rather than reflecting Persian traditions. To illustrate both this Egyptian influence and the hopeless confusion caused by the mysterious authorship of these texts, we’ll look at one of Quack’s examples: the Greek alchemical text Physica et Mystica, in which Democritus is initiated into the mysteries of alchemy by Ostanes. In the text, this initiation takes place in Egypt. We know that the book was not written by Democritus, but rather by the aforementioned Hellenized Egyptian author Bolus of Mendes. Still, one might be tempted to imagine despite the spurious authorship that perhaps Ostanes had lived in Egypt, but the fact that the story goes on to introduce Ostanes’s son, who is also named Ostanes, makes even one disposed to believing the myths wonder just how many Ostaneses and Zoroasters there might have been.

Quack concludes his study by theorizing that the authors of these Magusean texts were Persians, but that they had for generations since Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Achaemenid empire been living in Egypt, their religious beliefs soaking up Egyptian esoteric thought. However, it seems just as likely that Egyptian esoteric writers, steeped in the magical traditions of that culture, which itself is long and varied, may have cloaked their writings in the guise of Eastern wisdom in order to introduce it to Hellenistic Greece, which was so enamored of ideas that originated in the Orient. In this way, the Hellenistic Greeks might be considered analogous to those in the Austro-German New Age movement that I discussed in my series on Nazi Occultism last year. Indeed, the mythical homeland of the ancient Persians recorded in the Zoroastrian Avesta is referred to as the Aryan Expanse. The word “Aryan” originated in Zoroastrian scripture, clearly as a cultural group, but eventually it would be twisted into a racial designation by those seeking to justify their feelings of superiority over others. Similarly, it seems Zoroaster and the ancient Persian religion that honors him may have been misappropriated in antiquity and used to put the more respectable face of the Magus on practices the Magi did not pioneer, creating perhaps the biggest misnomer in history, forever after attaching their name to dark arts that may in fact have come from ancient Egypt.

Further Reading

Dannenfeldt, Karl H. “The Pseudo-Zoroastrian Oracles in the Renaissance.” Studies in the Renaissance, vol. 4, 1957, pp. 7–30. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2857138. Accessed 12 Mar. 2020.

Kingsley, Peter. “The Greek Origin of the Sixth-Century Dating of Zoroaster.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, vol. 53, no. 2, 1990, pp. 245–265. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/619232. Accessed 12 Mar. 2020.

Rose, Jenny. Zoroastrianism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Continuum International, 2011.

Skjaervo, Prods Oktor. The Spirit of Zoroastrianism. Yale University Press, 2011.

Quack, Joachim Friedrich. “Les Mages Égyptianisés? Remarks on Some Surprising Points in Supposedly Magusean Texts.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 65, no. 4, 2006, pp. 267–282. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/511102. Accessed 12 Mar. 2020.