Drake's Plate: A Brazen Plot

In the summer of 1579, Sir Francis Drake, an English privateer on a secret mission for Queen Elizabeth, made landfall on the other side of the world. He had embarked with five ships in 1577, tasked with sailing around South America to the Pacific and capturing Spanish treasure galleons off of Peru and up the coast of the Americas. After much attrition, with his fleet reduced to one ship, the Golden Hind, he struck out north in search of the Northwest Passage, a much theorized route through the Arctic Ocean that not only would have taken him back to Europe but also would have proven to be a valuable trade route. Turning back due to inclement weather, he landed in 1579 in a beautiful place that he dubbed Nova Albion. This port was somewhere on the coast of modern day California. He encamped there for five weeks, gathering provisions and repairing the Golden Hind in preparation for circumnavigating the globe. Before their departure, he erected a small monument, a plate of brass declaring the land property of Elizabeth I, asserting that the natives of the region had freely given up rights of ownership to Her Majesty, and affixing a coin within a hole in the plate so as to leave there a picture of the queen. The details of this secret mission were kept confidential for more than 10 years, and eventually all the first-hand reports of his voyage would be lost in a fire at Whitehall Palace in 1698. But second-hand reports and Drake’s own later mention of this brass plate affixed to a post somewhere in California, evidence of the earliest English landing in America and their first contact with Native Americans, have long tantalized historians, making it a McGuffin to rival any that Indiana Jones ever pursued, and the story of its eventual discovery is a saga all its own.

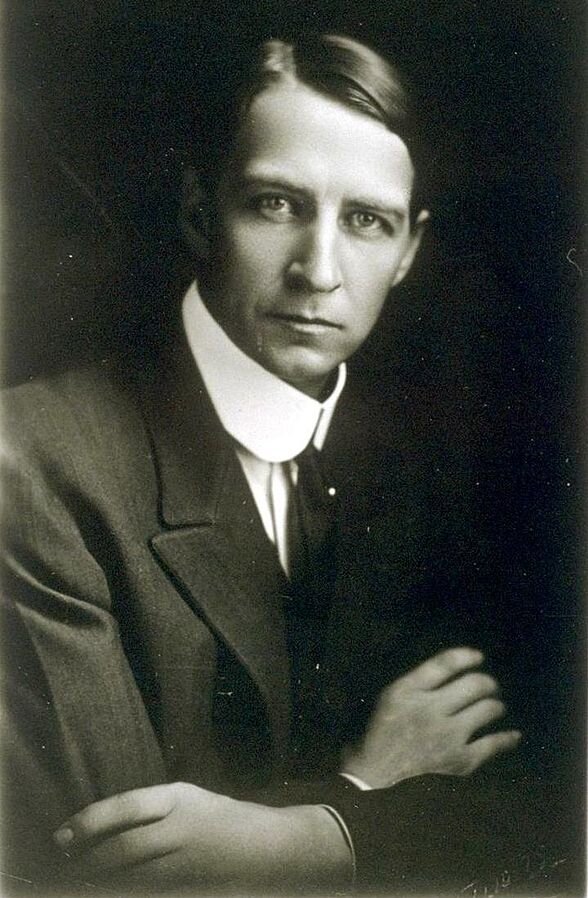

In the Introduction of this paper, I’d certainly want to thank all the investors and supporters of the academic study, especially the new contributors, like so-and-so. I’d especially like to thank Karen, who after my recent announcement that I’d be suspending the billing of my patrons during the pandemic chose to bankroll the project with a generous one-time donation on my website. Thanks again, Karen. [Hi Patrons! In the next episode] In this episode, I tell a story that I wanted to include in my episode on E Clampus Vitus, but which was too big to encompass in a mere paragraph at the end of the episode. It involves some prominent members of the Yerba Buena Chapter Redivivus, which was responsible for reviving E Clampus Vitus in the 1930s. This group’s rank and file was full of professional historians, officers of historical societies, journal publishers, and artifact collectors. One among these was the famed historian of the American West, Herbert Eugene Bolton, the originator of an entire theory and school of American historiography whose principal tenet was that U.S. history can only be properly understood in context with the history of all colonial powers and other American countries influenced by colonialism. He spent most of his career at the University of California, Berkeley, where he helped to establish the Bancroft Library as a major center for research. It was here that he held forth in classes of up to a thousand students about the legendary lost artifact of English colonialism that haunted him: the brass plate reportedly left behind by Sir Francis Drake at his landing place in California. It was a mystery he had always hoped to solve before the conclusion of his long and lauded career, and he regularly urged his students to search for it, marshalling them to his cause like his own personal expeditionary force. Thus it perhaps did not come as much of a surprise when, in February 1937, someone came to him with an artifact that appeared to be the very plate of brass he had so long yearned to hold in his hands. And what better person to scrutinize such a find and verify its authenticity? Surely he, of all experts, was best equipped to detect a fraud. But could the desire for it to be genuine have clouded even this eminent scholar’s shrewd judgment?

Herbert Eugene Bolton in 1905, via Wikimedia Commons

In the summer of 1936, one Beryle Shinn, employee of an Oakland dry goods store, was driving along a road near Corte Madera Creek, not far from San Quentin Prison in the Bay Area, when his tire went flat, forcing him to coast over to the shoulder. As a Clamper version of the story would later tell it, he then felt the need to defecate, so he went in search of a secluded spot to relieve himself. Through a fence he went, and up a ridge to a rocky outcropping where he enjoyed a gorgeous vista while emptying his bowels. It was then, as he groped about for something with which to wipe his posterior, that his hand came to rest on a blackened sheet of metal. He carried the plate back to his car, not because he believed it to be valuable, but because he thought it might be useful in repairing his car, which besides a burst tire apparently also had a hole in its cabin. It was months before he decided to try his hand at fixing his vehicle using the metal plate, though, and when he looked at it again, he saw that it bore some kind of inscription. Scraping and wiping off the soiled surface, he saw a date etched onto its face: 1579. Shinn then showed the plate to a co-worker at his store who just happened to be a UC Berkeley student. Recognizing the name “Drake” in the plate’s inscription and being aware of Professor Bolton’s longstanding search for Drake’s plate, this co-worker urged Shinn to take the artifact to Bolton. Herbert Bolton was, of course, ecstatic at the sight of it. He was 67 years old at the time and believed that the discovery of Drake’s Plate could serve as the culmination of his already impressive career. Right away, he brought in Allen Chickering, President of the California Historical Society, hoping to raise the money to buy it from Shinn before the clerk realized how much the item might actually fetch at auction. The two of them went out to the place where Shinn claimed to have found it, and afterward, they made an offer of $2,500 to buy it. At this point, Shinn started playing hard to get and even gave them a scare by taking the plate back home and going incommunicado for most of a week. Chickering, worried about losing the find, went all in, offering $3,500 and writing up a statement that took sole responsibility for the plate if disputes of ownership were raised or even if allegations of fraud were made. Shinn took the deal, leaving both Bolton, Chickering, and the Historical Society financially invested in a historical find they had yet to test for authenticity.

These parties were not the only ones concerned about proving the find genuine. Robert Gordon Sproul, the President of UC Berkeley, was also growing concerned, wary that Bolton may have blundered in rushing to acquire the object. The place it had been found, after all, was far from Drake’s Bay, where it had always been thought that Drake had landed. Bolton reassured him, though, that the appropriate tests would of course be performed. However, after performing no further tests beyond comparing the text inscribed on the plate with the surviving descriptions of the historical plate, he published a work and declared to the public that the plate had “apparently” been found, asserting that “[t]he authenticity of the tablet seems to me beyond all reasonable doubt.” The plot thickened, however, a few days after the news of the find spread, when a chauffeur named William Caldeira came forward to say that he had seen that plate back in 1933. According to him, he had driven his client, another member of the California Historical Society, out to Drake’s Bay to do some hunting, and while he waited, he poked around the car and found the plate. He had wanted to show it to the Historical Society member whom he was driving, but it was too dark to examine it, so he just stuck it in his car door pocket. A couple weeks later, while cleaning out his car, he decided it was garbage and tossed it out on the side of a road near San Quentin. This account resolved the issue of the plate’s discovery so far from Drake’s Bay, where it had long been agreed Drake had landed. But there still remained the mystery of how it had gotten from the roadside to the ridgetop. Further testimony emerged, however, to account for this discrepancy as well. One Joseph Cattaneo, apparently a convict returning to the prison at San Quentin, saw the plate on the side of the road in 1936 and carried it up to the hilltop to conceal it for later retrieval. This seemed to explain everything… except there was another claim, by one Florence Schatti, that she and her friend had seen the plate on the hilltop where Shinn would find it two years before Cattaneo claims to have carried it there. Someone appeared to be mistaken or lying.

San Quentin Prison, as it appeared in the 1930s, via These Americans

Suspicions lingered, and when a manuscript specialist named Henry Haseldon wrote a paper in September questioning the plate’s authenticity, Bolton and Chickering were quick to defend the artifact and the honesty of both Shinn and Caldeira. To answer any further criticism, the University and the Historical Society engaged a respected metallurgist named Cohn Fink to perform electrochemical tests on the plate. For seven months, he and his team completed a battery of tests on the artifact, and their report affirmed that the composition of the alloy and the patina all stood up to scrutiny as originating from the time of Sir Francis Drake. To protests that the plate was actual brass, as in an alloy of copper and zinc, whereas the Old English word “brasse” as used on the plate actually referred to bronze as only alloys of copper and tin were made in England at the time, their explanation was that the plate itself must have been of Spanish origin—an acceptable explanation since Drake had been seizing Spanish goods and treasure throughout his voyage. As for why the plate lacked the green oxidization known as verdigris that would be expected on a brass plate of such age, their simplistic answer was that it must have been because California’s climate was so mild. Despite the lameness of these defenses, their report was generally accepted. By the end of that same year, the plate was a centerpiece of the Golden Gate International Exposition, and in the years to follow, it would be featured as the authentic Drake plate in numerous textbooks, histories, and magazines, including National Geographic. Copies were given to Lady Bird Johnson when she was the First Lady and more than once to Queen Elizabeth II. Nevertheless, whispers behind the scenes continued, suggesting the find was a fraud, and even hinting at inside knowledge of who had perpetrated it. And eventually, in the 1970s, the truth became known. The plate of brass was indeed a hoax, one perpetrated by members of Bolton’s own roisterous chapter of E Clampus Vitus, and they had given him every opportunity to realize it and save himself from the disgrace of ending his career as the butt of a joke.

The members of Chapter Redivivus of course knew of Professor Bolton’s preoccupation with the Drake Plate, and so, being diehard pranksters, they saw a perfect opportunity to play a joke on their fellow Clamper. George Ezra Dane, who had co-founded Chapter Redivivus and resuscitated the Order of E Clampus Vitus along with Carl Wheat, was responsible for initiating the prank. He asked fellow Clamper George Barron, curator of San Francisco’s de Young Museum, to design the plate, which he did, writing the inscription based on the account of the plate written in Drake’s The World Encompassed. He didn’t bother much to get the orthography and phraseology historically accurate, since the hoax, it seems, was never meant to do any more than vex Herbert Bolton. Mostly, he just replaced U’s with V’s. He bought the plate itself, a piece of rolled brass, from a ship chandlery in Alameda and had his neighbor, an artist, inscribe it using a hammer and chisel. The letters were all caps, not Elizabethan at all, but again, this was just a silly joke, they thought. In fact, the artist who inscribed it even left a signature, a large C with a little capital G inside it, for George Clark. And to top it off, before planting it somewhere they hoped it would be found, they actually daubed the back of the plate with the letters ECV, for E Clampus Vitus, in fluorescent paint, so that under certain light, the identity of the pranksters would be revealed. Imagine their delight when, according to plan, it was discovered and brought to Bolton and he fell for it! Then imagine their unease when Bolton convinced the President of the California Historical Society, on whose board of directors George Ezra Dane sat, to invest an enormous sum in buying the plate and accept responsibility for it. Finally, imagine their dread when expert after expert appeared to confirm the plate’s authenticity, explaining away all the obvious problems with it. It’s an alloy that the English didn’t make? Well, it must be something Drake picked up along the way. No verdigris? California has a miraculous climate that causes no rust, I guess. Even George Clark’s signature, the G within the C, they explained as being a title of Drake’s, Captain General, although this was not a title in use at the time. And the hammer marks all along the edges of the brass, applied to hide the signs of its commercial shearing, and on the surface of the plate, where Clark had attempted to flatten lettering that had been raised by his chiseling method? Those had clearly been made by the poor wretch tasked with attaching the plate to the “great post” Drake had described. Surely that poor man’s thumbs had been much abused by the errant hammer that day. But perhaps most shocking was the fact that a team of scientists failed to notice the fluorescent confession painted on the back of the plate.

The supposed Drake Plate pictured with the hammering plate used by its counterfeiters to planish it, licensed by a Creative Commons International Attribution-ShareAlike license from creator Robert Stupack, via Wikimedia Commons

Dane and the other Clampers in the California Historical Society could not easily come forward once the hoax had gone that far, so instead they tried to nudge Bolton into a realization of the fraud. In May, the month after Bolton’s initial pronouncement of its authenticity, his Clamper friends dedicated a plaque near Tuoloumne City that was itself a brass plate with chiseled lettering that replaced U’s with V’s. This one was dedicated by Chief William Fuller of the mi-Wuk tribe, and it revoked the grant of land supposedly surrendered to Sir Francis Drake and Queen Elizabeth so long ago. Clearly, at least in part, the stunt was meant to show Bolton how a similar plate could easily be manufactured, but Bolton appeared not to take note, as he was more concerned by the scholarly challenges to the plate’s authenticity that had begun to appear. Then in September, one Clamper of the Yerba Buena Chapter sent a letter to Bolton purporting to be from “Consolidated Brasse and Novelty Company,” hinting at the modern manufacture of the plate by saying, “I am sure you will be interested in our special line of brass plates. These plates have a beautiful finish. We make them in all sizes and shapes and in a variety of scripts and dates. We have a very attractive Elizabethan line….” Bolton either failed to understand the letter or assumed the letter was itself a prank and continued in his course seeking evidence of the plate’s authenticity. Finally, his Chapter of the Clampers release a new book of tall tales about the exploits of ancient Vituscan brothers, and the first entry in this anthology was all about the newfound Drake plate. In it, they detailed its discovery as well as its testing, carefully pointing out every reason to doubt its authenticity. It featured a frontispiece drawing of the ancient chief Hi-Oh of the Mi-Wuks who was said to have given his tribe’s land to the English and in their version was said to have used the plate as a piece of jewelry after Drake departed. Around his neck in the sketch he wore the plate, on which can be seen the letters ECV, a hint at the invisible signature on its backside, and in their account, it even indicates that these letters can be seen using ultra violet fluorescence or infra-red light. According to their fanciful version of Drake’s account, the plate had been inscribed by Drake’s chaplain, a member of E Clampus Vitus, and so, cleverly, the story ends with the confession, hidden in plain sight, that the plate was “the rightful property of our ancient Order.”

But as we have seen, none of their efforts were successful. Professor Herbert Bolton was so intent on this artifact being the real deal that he made sure it was found to be so, and he was aided in his endeavor by many a scholar and scientist who likewise wanted to believe. Dane and the other Clamper perpetrators of the fraud simply gave up and let their prank become accepted history, thereafter only discussing their part in the hoax in whispers. Eventually, long after Bolton went to his final rest satisfied with the plate’s legitimacy, these whispers caused other scholars to look closer and to discover the fraud, and so today this is no longer a Blind Spot. However, enough unanswered questions remain that some continue to have doubts. When did the Clampers create the plate, and where did they plant it? It seems impossible that they would have planted it anywhere other than Drake’s Bay, so had they been disappointed when their fake plate disappeared and then surprised when it appeared again all the way over by San Quentin and still made its way to their mark, Bolton? Or was Shinn working for them? If so, what about Caldeira and the others with their conflicting testimonies? Some have even suggested that there were two plates, that which had been found in Drake’s Bay and lost again years earlier, and that which had been brought to Bolton. Could one of them have been the real Drake Plate? Or is the real plate lost forever, a missing piece of our past? Or was there never a plate to begin with, as some have suggested, and was the whole story of a monument marking a land deal with the natives concocted by Drake to strengthen English colonial claims to the New World? These are questions we may never answer, unless some sharp-eyed Californian manages to dig up the genuine plate of brass left by Sir Francis Drake in Nova Albion.

Clamper plaque recreating their handiwork in the supposed Drake Plate, via Find A Grave

Further Reading

E Clampus Vitus: Anthology of New Dispensation Lore. Edited by Thomas Duncan, Lulu Press, 2009.

Von der Porten, Edward, et al. "Who made Drake's plate of brass? Hint: it wasn't Francis Drake." California History, vol. 81, no. 2, 2002, p. 116+. Gale General OneFile, https://link-gale-com.libdbmjc.yosemite.edu/apps/doc/A104669394/GPS?u=modestojc_main&sid=GPS&xid=442e7652. Accessed 2 Apr. 2020.