The Piltdown Fraud: Fundamentalists Favorite Fake Fossil

When you hear the word “creature,” what comes to mind? We think of an animal, perhaps, a “lower” form of life, since the word can bear a negative connotation when applied to human beings. If a person is seen as a creature, it may be because they are seen as a servile tool being used by another, their creature. If you play Dungeons and Dragons, maybe you think of it as any living thing, but do you think of it as a tacitly religious term, supporting the notion of Creationism, of the origin of organisms through an act of divine creation rather than through the natural process of evolution? If we look at the etymology, “creature” comes from the Latin verb for creation. We might interpret this only to mean that organisms are created through reproduction, but the word was long historically associated in Old French with the notion of all the world as God’s Creation. Thus a creature is part of Creation. It’s not surprising that ancient religious ideas about our origins remain woven into the very fabric of our language, even though science has helped us achieve a clearer understanding of the evolution of populations through natural selection. Throughout the 20th century, Creationism has lost its cultural cachet as a viable scientific idea. Those who would like to see divine creation taught as a coequal scientific theory have had to rebrand the idea as Creation Science and Intelligent Design, but offering no actual testable, reproducible, or falsifiable evidence, their claims cannot be considered science and to enforce their instruction in science classrooms would violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment separating church and state, as has been decided in numerous Supreme Court challenges, most recently in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District in 2005. Tellingly, in searching for some scientific proof for their religious belief, Creationists rely on outmoded thought. A favorite “proof” of Intelligent Design is the metaphor of a watch in a field, and how if one found such a complex device, it is far more logical to reason that it was created by some intelligent inventor and left there rather than formed by natural forces. This pithy analogy actually was first used in 1802, by Anglican clergyman William Paley, and even at the time it was absolutely deconstructed and shown to be fallacious by Enlightenment scholar David Hume. But more than that, Charles Darwin, who had previously been convinced by Paley’s arguments, would eventually disprove them through his observations of gradual changes in populations, demonstrating how complex organic structures could take shape over generations as inherited features. Beyond long discredited ideas like that, Creationists also seize on the idea of a “Missing Link,” suggesting that proof of evolution requires proof of an intermediate state between lower and higher life forms, and they complain that such links are exactly that, missing from the fossil record. Of course, many a Creationist might dismiss the fossil record altogether as a kind of prank planted into the Earth to test the faith of Christians, as they have claimed about dinosaur bones in their insistence on the young age of the Earth. But this idea of a Missing Link also derives from outdated ideas. It partakes of the ancient philosophy of the Great Chain of Being, in which there is a hierarchy of lower and higher animals, each creature having been formed perfectly with all its distinctions by God. What Darwin and evolutionary science have shown is that there was not a linear chain of species, but rather a kind of tree of life branching in many directions from various roots. Thus, paleontologists prefer the term “intermediate” or “transitional form,” and though Creationists may claim that these “links” are missing, in fact they were even found in Darwin’s lifetime. In 1863, he learned of the discovery of Archaeopteryx, a fossil that shows feathers and other anatomical structures peculiar to birds as well as saurian features, demonstrating the evolution of dinosaurs into birds. Beyond that, the fossils of intermediate forms revealing the evolution of many other species, including mollusks, fish, whales, and horses, have been discovered. But Creationists cry out for the Missing Link connecting monkeys to human beings, often demonstrating a fundamental misunderstanding of evolutionary theory, which does not assert that Homo sapiens are descended from monkeys but rather that they both are descended from a common ancestor, which would be recognized as an entirely different species. And despite what preachers may tell their congregations from the pulpit, there is no shortage of these intermediate forms either. Paleontologists have pieced together the timeline of our evolution from the earliest apes in the Miocene epoch between 23 and 5 million years ago, with the first evidence of bipedal movement occurring after the last of our common ancestors with gorillas and chimps, as evidenced in Sahelanthropus tchadensis. In the Pliocene, we see the development of our Hominin ancestors and the early use of stone tools, with the transitional species Ardipithecus and Australopithecus, like the fossil named “Lucy,” who was bipedal but had a small skull. From the Pleistocene epoch, paleontologists have pieced together some 20 or so transitional hominin forms, some our own ancestors and some from other branches of the tree of life: Heidelberg Man and Java Man—both examples of Homo erectus—the Old Man of La Chapelle, a Neanderthal; The Taung Child, Peking Man, the Little Lady of Flores. The list goes on and on, even up to 2008, when the 9-year-old son of a paleontologist in South Africa found a new and distinct subspecies of Australopithecus named sediba. When pressed on the fossil evidence, though, Creationists are likely to just dismiss all of it as untrustworthy, casting doubt based on the fact that there have, in the past, been fake fossils. In this, they are cherry picking, placing undue emphasis on one notorious hoax that eventually was exposed by scientists themselves. This is Historical Blindness. I’m Nathaniel Lloyd, and here I need to tread carefully, gently brushing the dust away to reveal a fascinating and extremely significant hoax while also recording its context in order to refute Creationists who tout it as evidence that evolutionary theory generally cannot be believed. Thank you for joining me as I discuss The Piltdown Fraud: Misuse of a False Fossil.

After the last blog post on the crystal skull forgeries, it made sense for me to move from one archaeological fraud to the story of this paleontological fraud, which I have long wanted to discuss. However, as I indicated, I am very conscious of how topics on this blog can actually be taken out of context to support misinformation. For example, I had a podcast listener write me last summer to tell me that my episode on MK-Ultra led them to give more credence to other conspiracy theories involving the CIA, including their involvement in the JFK assassination. While I can absolutely understand the story of MK-Ultra leading one to healthy sense of mistrust when it comes to the U.S. intelligence apparatus, my discussion of their publicly exposed efforts to develop mind control technology in no way stands as evidence in support of any other conspiracy claims. Likewise, recently, I noticed someone using promotional materials for my podcast to promote the Tartaria conspiracy theory. Though I was recently kicked off of TikTok when I was posting about my episodes on the death of Hitler and the Hitler’s diaries hoax—I believe because of one disgruntled admirer of Hitler who defaced my posts with pro-Hitler sentiments and who I believe may have wrongfully reported me as spreading hate speech (when in fact he was)—I have still been able to search TikTok on my desktop browser. While researching the last patron exclusive minisode, which went into the republic of the Russian Federation sometimes called Tataria, I did an image search to find a map, and I discovered that numerous promoters of the ridiculous Tartaria fraud are using the title card I created for my episode as the background for their little talking head videos. It’s a historic image of some brick layers working in the foreground with the Renaissance-style Iowa State Capitol looming in the background, and I added the title “The Lost Empire of Tartaria.” It was part of my ruse as an April Fool’s joke to act like there was something to this baseless conspiracy delusion in the episode’s cold open, but now I’m kicking myself, because the image is being widely used to promote those false claims. If only I’d been clear from the start and called it “The Myth of the Lost Empire of Tartaria,” or something, then they couldn’t use it or would have to put in more effort to make their own image. So I’ve decided that, from now on, my titles will make it abundantly clear when a topic I’m tackling is total bunk, and I will be doing all I can, at the beginning of episodes and and these accompanying blog posts, to clarify the truth, to debunk from the outset rather than playing it coy and building up to the reality of things. Because of that, at the beginning of this post, I want to talk a bit more about the flaws in Creationist arguments before I really dig into the one example of a fossil hoax they’re so fond of touting.

A diagram demonstrating the similarity of hominoid skeletal structure.

Proponents of Intelligent Design as a scientific theory will delve into very specific biological minutiae in order to argue that evolution cannot be true. They will say that there is no way eyes could have evolved because they are too complex, or that the propeller-like flagellum of bacteria are too complicated and must have been engineered. Actually, these are just the old “watch in a field” argument wearing different clothes, and in reality, biologists have observed more primitive versions of light-sensing organs and simpler flagellae, demonstrating the fact that these structures too developed slowly over time. And it’s funny that Creationists would point to bacteria to prove their views, since on a microevolutionary level, we see evolution today in the form of bacteria adapting to resist antibiotics. The fact is that almost all Creationists believe in evolutionary theory at the microevolutionary level, since few can reasonably deny the truth of viruses evolving resistant variants or insects evolving resistance to pesticide, and the common practices of plant and animal breeding show clearly how traits are inherited and change populations in sometimes dramatic ways. It’s usually only the implications of macroevolution, which involves speciation, that they reject. Perhaps the most common objection that Creationists rely on is that evolution is “just a theory,” and theories aren’t proven fact or necessarily true, and they will try to suggest that intelligent design is equally a theory by the dictionary definition, in that it too is an idea to explain something. But this relies on a grammar school understanding of the scientific process. The scientific community uses the term “theory” to denote an explanation that is substantiated with evidence. In reality, evolution meets the criteria of being considered a fact, as according to the National Academy of Sciences, a fact is “an observation that has been repeatedly confirmed and for all practical purposes is accepted as ‘true.’” Therefore, I will mostly try to refer to evolutionary science, rather than evolutionary theory, in order to avoid any hairsplitting over terminology. Creationists will claim that there is no scientific consensus, cherry-picking an outlier academic here or there that seems to be anti-evolution. This is just false, though, as was shown in numerous independent surveys of academic literature since the 1990s, conducted in efforts to determine the prominence of Intelligent Design views in academia, which found that no scientific studies supporting the claims of so-called “Creation Science” are published at all. The closest thing to it are papers by anti-evolution authors that do little more than highlight areas of uncertainty that the scientific community does not dispute. And any claims that academic publishers censor them and refuse to publish the findings of “Creation Science” are also refuted by the statements of major scholarly journal editors that few such manuscripts are even submitted for their consideration. The fact is that evolution science is consensus among experts because it has never been falsified by evidence. In other words, all study has helped to prove it’s true. Yes, evolutionary biologists disagree with each other on particulars, but not on the principles of evolutionary biology generally. This disagreement is part of the scientific process, and it’s why frauds like Piltdown Man are inevitably exposed.

In the autumn of 1812, rumors in the British press had begun to circulate that there had been an important paleontological find in Sussex, at Piltdown in Southern England. At a momentous meeting of the Geological Society of London, in December of that year, this find was finally revealed. Arthur Smith Woodward, a geologist with the British Museum, revealed that earlier that year, his friend Charles Dawson, a solicitor and amateur antiquarian, had written to him about a curious gravel pit near Barkham Manor, a Georgian mansion dating to the 18th century. Dawson told him that he had been curious of the brown flintstones in the gravel, as stone of that sort was known to have been used for crafting tools in the Stone Age. Dawson had asked the workers in the pit to keep an eye out for anything interesting, and on a return visit, one of them handed him a piece of an unusually thick skull. After finding yet another piece of what appeared to be the same skull in the gravel bed on a subsequent visit, Dawson had reached out to Woodward, and the two had undertaken a careful excavation of the pit throughout that summer. At first, they kept their efforts secret, bringing in only the French Jesuit prehistorian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. They discovered seven fragments of the same skull, as well as half of a jaw with two intact molars, and in the same context, they discovered various Paleolithic stone tools and the fossilized bones of horses, deer, hippopotomi, elephants, and mastodon, which appeared to confirm the great age of the fossilized human remains. By summer the following year, Woodward had completed a reconstruction of the skull and presented it to anatomists at the International Congress of Medicine, and the importance of the find became even clearer. While Piltdown Man appeared to have an apelike jaw and thick skull, it had a braincase that would accommodate a fully-developed modern human brain. There were definite features of both ape and man present in the reconstruction, even in just the jaw fragment alone, which showed apelike morphology and yet had deep-rooted molars like those of a human. So it appeared that the much sought after “Missing Link” had been discovered, right there in England, just 44 miles from London, a hub of modern scholarship in paleontology. And more than that, this new find appeared to confirm what most British paleontologists and evolutionary biologists theorized at the time. And perhaps more importantly, it also appealed to everyday English men and women everywhere, stoking nationalism and inflating racial pride.

The Piltdown skull reconstruction

At the beginning of the 20th century, a notion had arisen among the paleo-intelligentsia that the large brain of Homo sapiens must have developed first, perhaps at the end of the Pliocene and beginning of the Pleistocene, before the loss of other apelike features in hominins. Previous candidates for the Missing Link had been the various Neanderthal fossils found in Germany and France, or Homo erectus, as observed in the Java Man fossil discovered in the 1890s. Those were at the time rejected as early human fossils because of their small braincases. In fact, Neanderthals had larger braincases but seemed smaller because it was more elongated. Regardless, Arthur Smith Woodward’s reconstruction of the Piltdown skull was seized on as an example of a seemingly transitional form between ape and man that showed early development of a large brain. It must be remembered that during this time, the old pseudoscience of craniometry, which attributed intelligence and personality traits to cranial measurements, was still clinging to life in academia. But Piltdown was also seized on for less academic reasons. Almost all major early human fossils to date had been discovered elsewhere in Europe. The Old Man of La Chappelle was discovered in France, the Engis skull in Belgium, and most galling to the English during the years preceding the Great War, several important fossils had been discovered in Germany, including the Feldhofer skull found in a valley from which Neanderthals take their name, and more recently, Homo heidelbergensis, found in Heidelberg. The British were desperate for some fossil man of their own, and this yearning can be discerned even in the first letter Dawson wrote to Woodward, in which he suggested his find “will rival H. heidelbergensis.” Not only would a British fossil allow British paleontologists an opportunity to study an important site without having to travel abroad, and not only would it allow them some bragging rights against their German rivals, but there was also the sense that finding the Missing Link in one’s country indicated that your country must have been the cradle of humanity and therefore of civilization. British paleontologists were eager to accept the Piltdown Man fraud because they wanted to believe in it. It meant they were right about the development of braincases, but it also meant that, though this might have gone without saying, maybe, just maybe, the first human being was English. And as if to emphasize this idea, the following year at the Piltdown site, a new tool was discovered, this one carved from an elephant bone—the earliest known bone tool—and it was shaped much like a cricket bat. It seemed the first man not only an Englishman but also a cricket player!

To be fair, paleontologists had some valid reasons for giving weight to the discovery as well. The specimens were seen by Smith Woodward, a respected expert, being picked up from a gravel bed in which had also been found paleolithic tools and extinct animal fossils. The context of the find alone appeared to confirm the legitimacy of the find, and this field site was widely photographed and visited by scientists who gave credence to the claim and lent it further legitimacy. As one might expect from a putative Missing Link, Piltdown Man very quickly became arguably the most famous fossil in the world. Even during the initial excavation of the gravel bed in Sussex it drew the attention of the aristocratic tenants living in area manor houses like the nearby Barkham Manor. Those who’ve watched Downton Abbey might imagine it vividly: “Some workmen are digging near the road causing quite the disturbance, and they say they’ve found some old bones there. How exciting!” During 1913, the Piltdown excavation became a popular day trip for Edwardian ladies and gentlemen, dressed in their finest picnicking clothes and driving out to have a look at the place where the Missing Link had been found. The number of photographs taken of the site and of the reconstruction of the Piltdown skull further propagated the hoax even among those who would never examine the actual fossils themselves. They were displayed in museums and used in education. One Belgian museum conservator even created a reconstruction of a living Piltdown Man from the waist up, a kind of noble looking humanlike ape, and this work of art was mass produced as a stereoscope card with the caption “Early Man.” Before long it was not only scholars who had staked their reputations on Piltdown, it was museums and media companies, and they were not just intellectually invested but also financially. This investment resulted in Piltdown being peddled as the end-all find of paleontology, to the detriment of legitimate new finds. For example, in 1925, more than a decade into the life of the Piltdown hoax, it was still going so strong that when the Taung Child, an almost 3 million year old fossil, was discovered in South Africa and showed a small braincase with more human features—exactly the opposite of what Piltdown showed—it was dismissed as a baby chimp. Piltdown not only fooled the scientific community, it also perpetuated a false notion about the evolution of human traits, as now it is more widely accepted that our large human brains were not among the first of our traits to develop.

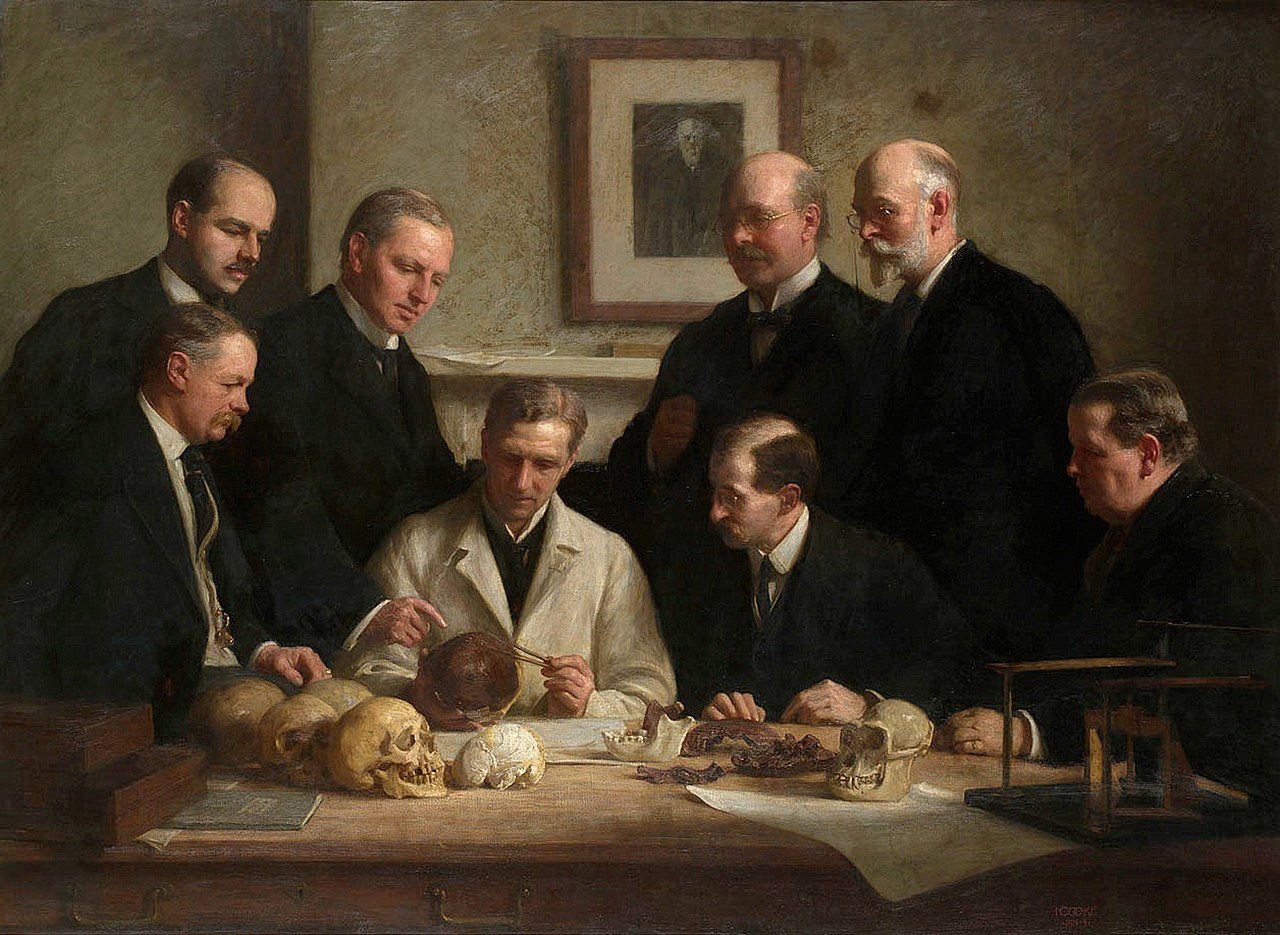

A portrait of the scientists who examined the Piltdown fossil. Charles Dawson and Arthur Smith Woodward are pictured in the back right.

It should be said, however, that acceptance of the Piltdown fossils was not universal and wholehearted. Of course, even then the fundamentalists cast doubt on the find, as they would on any transitional fossil that appeared to confirm Darwinian evolution. Most famously, the lawyer William Jennings Bryan, who had been a progressive reformer in the Democratic Party and later in his career turned his attention to religious fundamentalist causes, acting as the prosecutor in the Scopes Monkey Trial, said of the Piltdown fossil, “The evolutionists have attempted to prove by circumstantial evidence (resemblances)that man is descended from the brute…. If they find a stray tooth in a gravel pit, they hold a conclave and fashion a creature such as they suppose the possessor of the tooth to have been, and then they shout derisively at Moses.” All bluster aside, in this instance, fundamentalist mistrust would be proven justified. But the fact is that there were scientists who also doubted Piltdown from the beginning. There was Arthur Keith, a museum conservator associated with the Royal College of Surgeons, who suggested that Woodward’s reconstruction of the skull was manifestly inaccurate. There was David Waterston, an anatomist with King’s College, who said the apelike jaw could not possibly have been from the same creature as the humanlike skull, despite the humanlike rooting of its molars, arguing they were two entirely different fossils. Across the Atlantic, in America, there were further grumblings by Gerrit Miller of the U.S. National Museum, who likewise believed the skull and jaw fragments were from two distinct fossil creatures. Eventually these holdouts were converted by further discoveries. In 1913, after some reservations were expressed about the suspicious fact that no eyetooth, or canine, had been found, as a canine tooth would certainly help to determine how apelike the Piltdown creature had been, suddenly an eyetooth was discovered in the gravel pit by the Jesuit, De Chardin, and it matched perfectly with Woodward’s reconstruction of what the half-ape and half-human canine might look like. And in 1915, finally laying to rest all doubts that the two fossils had been from different creatures, Dawson just happened to discover an entirely different set of fossil remains two miles distant from the first site, complete with very similar skull fragments and another human-like molar, along with a Pleistocene-era rhinoceros tooth to provide some sense of its age. This finally quieted most critics, although some continued to doubt. Decades later, their doubts would be vindicated, as scientific testing proved that, not only were the skull and jaw fragments from different creatures, as long suspected by some, but also that the whole thing had been a carefully crafted fraud.

In the 1940s, as misgivings and suspicions about Piltdown had steadily resurged, a way to test the fossils was discovered. The fragments that comprise the Java Man fossil had recently been proven to have come from a single individual through fluorine testing. Throughout a creature’s lifetime, its bones absorb the same amount of fluorine from the water it drinks, so a test of fossilized remains could determine whether fragments were all from the same creature by determining if they all contained the same amount of fluorine. When the tests were conducted in 1948, sure enough, the jaw and skull contained differing levels of fluorine, proving that despite their being found close together and being the exact same brownish color, they were not from a single creature. Since this initial debunking, further chemical tests were able to prove that the remains are far younger than originally believed, despite having been found with animal remains from the Pleistocene, suggesting they may have been planted there. And any further doubts about whether it had been a deliberate hoax evaporated when powerful modern microscopes revealed that the fossils had been doctored. As long suspected by many, the skull fragments were human, unusually thick but within normal human ranges, and the mandible and teeth were from a young orangutan. The hoaxer or hoaxers knew what they were doing. They had filed down teeth in an orangutan jaw to make them appear more human, and they had even gone so far as to drill into the mandible to widen the root holes and make the molars appear more deeply rooted in the human fashion, filling in the roots with gravel and putty. And they had artificially aged all of the fragments with an iron solution to give them all the exact same brown hue. Since these discoveries, the central mystery surrounding Piltdown has been the identity of the hoaxer. Was it a single person or a conspiracy? There have been many suspects. The most outrageous is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, who lived nearby and regularly golfed near the Piltdown site and was known to collect fossils and enjoy a good practical joke. It has been suggested that Doyle, a believer in spiritualism, might have been motivated to make the scientific community and their focus on materialism look foolish in retaliation for their scorn for spiritualism. Another suspect was a young member of the Natural History Museum staff, Martin Hinton. In 1970, a trunk of his was discovered that contained bones that had been filed and stained in the same manner as the Piltdown fragments. According to this theory, Hinton had some personal and intellectual differences with Arthur Smith Woodward and wanted to make him look the fool. The major problem with these theories, as I see it, is that both men went to their deaths without ever revealing that they had played the prank, the whole point of which would have been that it is revealed to be a fraud and thus make those who believed it look foolish.

Charles Dawson, the prime suspect in the forgery.

The most likely scenario involves one or all of the three men who initially undertook the excavation of Piltdown in secrecy, Arthur Smith Woodward, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Charles Dawson. Indeed, those who believe in a conspiracy to perpetrate the hoax typically focus on these three. De Chardin is interesting as a suspect because he personally found the eyetooth, but he was a serious scientist who would later help to discover the authentic fossil remains of Peking Man in China. The theory put forward of why he would be involved is also rather flimsy, suggesting that as a Frenchman he just wanted to make British paleontologists look foolish. According to those who knew him best, this was not in his character. As for Arthur Smith Woodward, I think it is safe to exclude him from any such conspiracy altogether. We have the evidence of the letters from Dawson to Woodward showing that he had been drawn to the Piltdown site after fragments were already discovered there, and the fact is that, after Charles Dawson died in 1916, Woodward continued to search for more fossils at Piltdown for nearly 30 years, never finding anything else. Indeed the very fact that Dawson was present at the discovery of or personally dug up every Piltdown find and that nothing else was ever found after his passing seems to implicate him the most. And there are further indications of his guilt as well. Though he was an amateur, he had long sought recognition among the scholarly community. He had a long-standing certificate of candidacy for the Royal Society that he renewed every year until his death, though he was never accepted. And he may not have shrunk from unethical efforts to receive that recognition. Before the Piltdown affair, he had written two volumes of a history of Hastings Castle and was afterward accused of plagiarizing most of it. One early version of the story he told about discovering the first skull fragment actually said that the worker who handed it to him said they thought it was a coconut, and this is actually identical to the story of the discovery of Java Man, indicating he may have even plagiarized his claims about finding the Piltdown fossil. And according to the most recent scientific investigations into the Piltdown hoax, published by Dawson’s beloved Royal Society, the inexpert forgery of the skull, which appears to have resulted in cracks and damage that had to be mended and covered up with putty, show that the forger was an amateur like Dawson, not a trained paleontologist like Woodward or De Chardin, or even a museum conservator like Martin Hinton. Furthermore, the techniques used by the forger are so consistent that they act as a signature, indicating one forger. In fact, in 2003, an archaeologist examined his antiquarian collection and found several fake artifacts, some showing the same telltale filing of teeth. Add to this the fact that bringing in an accomplice would have introduced a far greater likelihood of exposure, and all signs point to Charles Dawson alone fabricating the Piltdown fragments and either pretending to find them in the Piltdown gravel or planting them where he knew his dupes would see them.

As a means of casting doubt on the consensus of the scientific community, the Piltdown fraud is perfect ammunition for Creationists. It does show that academics are prone to error, like any human beings, and that they seek to preserve and support their own pet theories, their prejudices. It also shows how peer pressure does exist, and casting doubt on accepted views can be discouraged. But it also shows how science inevitably corrects itself because of the power of evidence and falsifiability. The scientific process wins out in the end, and the fact is that, with the development of sophisticated tests such as have been used to reveal Piltdown, a hoax of such a massive scale could not happen again. No, scientists are not infallible, but they may be more likely to examine their preconceptions than theologians, as their entire worldview is based on the correction of false ideas and the empirical building of knowledge. This is not to say that scientists know everything about our origins either. It’s true that we do not yet know with any certainty how life originated, although biochemists have a strong idea of how it may have begun from basic building blocks, and astrochemists have provided some further idea of how comets may have brought those building blocks to Earth. But the thing is, we don’t have to know how life first appeared to acknowledge the fact of how it has evolved. And there are many, many people of strong religious faith who accept this. Some of the keenest minds in Christianity don’t reject science but rather reconcile their faith with the fact of evolution. Darwin himself had been on the path of becoming a clergyman before taking an interest in natural history, and he said himself that he had “never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God.” The Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin had reconciled his Christian faith with the principles of evolution, as had Raymond Dart, the discoverer of the Taung Child. Famous novelist and Christian apologist C.S. Lewis reconciled the two with this elegant and concise turn of phrase: “For long centuries God perfected the animal form which was to become the vehicle of humanity and the image of Himself.” And the influential evangelist Billy Graham admitted “The bible is not a book of science” and reconciled his faith with biological evolution by stating, “I believe that God created man, …whether it came by an evolutionary process…or not.” Even the last two Popes have reconciled with science, with Benedict XVI calling them “complementary—rather than mutually exclusive—realities” and Francis asserting that “[t]he evolution of nature does not contrast with the notion of creation.” I think fundamentalists can learn a thing or two from these figures. If one feels their faith is threatened by science, then their faith is simply not very strong, because the fact is that faith and science are neither compatible nor in conflict. They are entirely unrelated realms of human thought…that were clearly developed following the evolution of larger brains.

Until next time, remember, When the latest scientific discovery is trumpeted in the press, give it a few years before you start placing too much weight on it.

Further Reading

Black, Riley. “What’s a ‘Missing Link’?” Smithsonian, 6 March 2018, www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/whats-missing-link-180968327/.

De Groote, Isabelle, et al. “New genetic and morphological evidence suggests a single hoaxer created ‘Piltdown man.’” Royal Society Open Science, 1 Aug. 2016, doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160328.

Kramer, Brad. “Famous Christians Who Believed Evolution is Compatible with Christian Faith.” BioLogos, 8 Aug. 2018, biologos.org/articles/famous-christians-who-believed-evolution-is-compatible-with-christian-faith?gad=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwldKmBhCCARIsAP-0rfziunqkYPe1whthvBLbHKBKcNaeqiGV-WOGIWIphFPx2ltaDLI7j90aAgOsEALw_wcB.

Price, Michael. “Study reveals culprit behind Piltdown Man, one of science's most famous hoaxes.” Science, 9 Aug. 2016, www.science.org/content/article/study-reveals-culprit-behind-piltdown-man-one-science-s-most-famous-hoaxes.

Pyne, Lydia. Seven Skeletons: The Evolution of the World’s Most Famous Human Fossils. Viking, 2016.

Rennie, John. “15 Answers to Creationist Nonsense.” Scientific American, 1 July 2002, www.scientificamerican.com/article/15-answers-to-creationist/.

“What Is the Evidence for Evolution?” BioLogos, 4 Nov. 2022, biologos.org/common-questions/what-is-the-evidence-for-evolution?gad=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwldKmBhCCARIsAP-0rfyUG_nCH4_0o0BRikNSP-5JtaRjCLjY2PfAvqwuQfKirToWTc8uDHIaAhu4EALw_wcB.