The Forging of the Crystal Skulls

There is no denying that the use of crystals to ensure health and wellness is ancient, as the modern purveyors of crystal healing will surely tell you. What they won’t tell you is that their use today differs fundamentally from their use in the past. Yes, crystals were used, as were almost every other precious stone, in the form of amulets worn for protection and good fortune in ancient Greece and Egypt. Different minerals were believed to have different uses or affect us in different ways, and as we have seen with all lore associated with magic and alchemy, these beliefs persisted, crossed cultural barriers, and evolved through the years into the Middle Ages, when the medicinal and magical properties of crystals and other minerals were catalogued in medical papyri and grimoires. But the use of crystals by New Age gurus today really is not based on historical practices, which fell out of favor in the 17th century as the medicinal powers attributed to crystals began to be attributed instead to the Christian God and his angels. New Age crystal healing really was invented in the 1980s, mostly attributed to the work of Katrina Raphaell, who took what had always been a folk tradition that relied on the placebo effect and transformed it into a modern pseudoscience with an elaborate mythos behind it. According to her, the “science” of crystal healing originated in Atlantis, which as so many have claimed through the ages, was a technologically advanced civilization that, according to Raphaell and the New Age movement, used crystals for telepathic purposes. She claims to possess and teach the supposedly Atlantean art of arranging crystals on the body in such a way that they activate the chakras, allowing one to access deeper levels of consciousness that enable self-healing. And of course, she sells the crystals that are needed. Crystals have become a billion dollar industry since the advent of the New Age movement, and the price can really be hiked if the crystal is claimed to be from Atlantis. Considering this phenomenon and subculture, it is perhaps unsurprising that the most famous and fabled of all crystal artifacts, the crystal skulls that appeared in the possession the Mesoamerican antiquities dealers between the 1870s and the 1930s, would eventually be claimed to have come from Atlantis and have the ability to heal or to kill, to reveal the past or the future. But even dismissing these claims out of hand, the simple claim that these crystal skulls are genuine Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican artifacts cannot be credited. Thus these hoax objects have a false history that has since been encircled by further false claims and pseudohistory, making them a perfect topic for this blog.

This is another of my posts exploring on the lore of the MacGuffins featured in Indiana Jones films, as obviously the fourth film, The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, featured a crystal skull as its main MacGuffin. Unlike some of the preceding films, which actually seemed well-read in the lore they explored, this one just mentions that Indy was “obsessed with the Mitchell-Hedges skull” in college… and that’s about it. The crystal skull in the film is not claimed to be one of the known crystal skulls and is shaped differently to look like an elongated skull, thus to connect with Peruvian skull modification and then, of course, to aliens. It might at first seem unrealistic to suggest that an archaeology student would be obsessed with the crystal skull, knowing as we do today that all of them were fakes, but that’s not really accurate. When the aforementioned Mitchell-Hedges skull came to the attention of the scholarly community in the 1930s, since it corresponded with another crystal skull in the possession of the British Museum, it actually did generate some interest. The timeline does not really work, though, since the watershed moment, a major article in the anthropology journal Man, did not come until 1936, at which time Indy was already a professor and international relic-hunter, not a student at University of Chicago. But it’s close enough for jazz, and indeed, the crystal skulls did interest some in the scholarly community at first, as they were at the time preoccupied with craniometry, but more so they interested the general public, especially in France, where these crystal skulls seem to have first appeared. In mid- to late-19th century Europe, there was a real market for trinkets symbolic of death, sold as mementos mori, kept to remind one of the inevitability of death. And in France in particular, a burgeoning industry of macabre art was booming. Stereoscopic cards were becoming more and more popular at the time. These were pairs of nearly identical photographs or prints that appeared three dimensional when viewed in a stereoscope. Think of the viewfinder toys of your youth, if you grew up in the eighties. Increasingly popular in France was a style of stereoscope card called Diableries, in which sculptures or devils and skeletons, often making satirical commentary on the corruption of Napoleon III and his court, came to life, with special effects like a red glow in the eyes of skulls when the lighting was right. Amplifying this was the French interest in Mexican culture, occasioned by Louis Napoleon’s invasion of the country and installment of Austrian archduke Maximilian von Hapsburg as its emperor. Anyone boasting even a passing familiarity with Mesoamerican cultures must be aware of the depiction of skeletons and skulls in their art going all the way back to the Aztecs. The Spanish tried to suppress skull art as pagan, but it remains common in the culture today, in syncretistic coexistence with Catholic traditions. When crystal skulls began to be sold in France in the latter half of the 19th-century, claimed to be Mesoamerican artifacts, they appealed to the European taste for the macabre as well as for the exotic.

A “Diablery,” image courtesy The London Stereoscopic Company.

These first crystal skulls were quite small, perhaps an inch high, and they each had a hole drilled vertically through them from the top of the skull downward, such that they could be worn like a bead. According to my principal source, the extensive work of Jane MacLaren Walsh on this subject, cited below, one of the first such crystal skulls was acquired in Mexico by a British banker sometime in the 1850s, and then two more were displayed at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867. A fourth was purchased in 1874 by the national museum, and a fifth in 1880. The Smithsonian purchased one from Mexico in 1886. There should have been more caution about the provenance and authenticity of these small crystal skull beads from the start, however, because there was nothing else like them in Mesoamerican art. As it turns out, it was exceedingly rare to find quartz artifacts, at least in controlled archaeological digs, whose finds can be trusted to be genuine. In fact, the sole piece of carved crystal known to have ever been discovered in a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican dig, at Monte Albán in southern Mexico, was a crystal goblet whose rough tool marks indicate the inability of Mesoamerican artists working with stone tools to achieve the kinds of workmanship we see in pretty much all crystal skulls. Any other Mesoamerican artifacts made of crystal are simply small ornaments, like beads. In fact, the Smithsonian’s crystal skull bead was determined in the 1950s to have been carved using a modern lapidary wheel, making it a definite fake, though the hole drilled through it may have been accomplished using more rudimentary tools. This raised the possibility that these small crystal skulls were genuine Mesoamerican crystal beads that had been altered using modern tools in order to make them appeal to European buyers. Indeed, an 18th century South American painting of Saint Teresa of Ávila depicts her wearing just such a skull charm on her rosary. It has been suggested that these skull beads, like the crucifix, may have represented a reminder of Christ’s Passion, which occurred on Golgotha, the hill on which he was crucified, whose name meant “place of the Skull.” This would suggest yet another, older market for such an artifact, giving further reason for their manufacture. But if these first crystal skulls were manufactured in the 19th century, or if they were perhaps simply 18th-century Spanish religious baubles misrepresented as ancient Mesoamerican artifacts, who was responsible for them? As it turns out, one man can be connected, at least circumstantially, to all of them. The two skulls exhibited in Paris at the Exhibition Universelle in 1867 were both from the collection of a French antiquities dealer who served as the official archaeologist of Emperor Maximilian in Mexico, where all the rest of the similar crystal skull beads had been sold to collectors. And this man, Eugène Boban, would later be tied to the emergence of the first life-size crystal skulls.

Boban had left Paris for the Americas at 19 years old, hoping to avoid Napoleon III’s draft and to strike gold in California. Unsuccessful in the gold fields, he came to Mexico City in 1857 and found a new way to strike it rich. After learning Spanish and the indigenous language of Nahuatl, he reinvented himself as an antiquities trader, doing a brisk business selling Aztec artifacts to tourists. About 20 years later, a Smithsonian archaeologist who visited the city warned his fellow scholars about the shops on every corner selling fake artifacts. It was this burgeoning trade in spurious antiquities that Boban helped to spearhead. When, after civil war, the Zapotec native Benito Juarez became president and began dismantling the Catholic churches that had been built on top of Aztec temples, Boban benefitted by acquiring a great deal of Spanish artifacts and art. Then, when Louis Napoleon invaded and established Maximilian as the Mexican Emperor, he benefited again, becoming the “antiquarian to the Emperor,” and amassing a large collection of pagan artifacts. It was Napoleon III’s Commission Scientifique that sent his collection to Paris to be exhibited in 1867, and two years later, Boban went there himself, hoping to sell his collection and finally get rich. He opened a curio shop called Antiquites Mexicaines. During his time there, he became a source for real skulls, which he sold and donated to anthropologists and anatomists. Perhaps having already observed the interest in small crystal skull baubles, and knowing the market for life-size skulls, he seems to have put the two together when he began exhibiting and offering for sale ever larger crystal skulls. In 1878, he sold a collection of small crystal skulls and one grapefruit-sized skull, which also had a hole drilled through it like all the others. Then in 1881, he began to display a life-size crystal skull with no hole drilled through it. These skulls came into his possession while he was in France, so either he had a pipeline direct from Mexico, where artifacts unlike any others ever seen before were promptly shipped to his antiquities shop, or he somehow found and purchased these artifacts from another dealer or a forger whose name he never revealed, or he simply made them himself. Even at the time there was suspicion about them. When his larger crystal skulls were exhibited publicly in Paris, they were displayed with the caveat that “the authenticity appears doubtful.” Unable to sell his life-size crystal skull, Boban returned with it to Mexico and began asserting it was a genuine Aztec artifact that had been discovered in a dig at Veracruz and attempting to sell it to the National Museum of Mexico. When the provenance and authenticity of the skull was challenged before its sale to the museum, and Boban accused of fraud, he hastily took his collection and fled to New York, where he thereafter managed to sell his crystal skull to Tiffany & Co. for an exorbitant price. About ten years later, Tiffany’s sold it to the British Museum, where for a long time it was displayed alongside genuine Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican artifacts as if it were authentic.

Eugène Boban with his collection of Mexican antiquities.

Cut to about 50 years later, in 1943, when a man named Frederick Mitchell-Hedges bid £400 in a Sotheby’s auction to acquire another crystal skull. This one was different from Boban’s skull in that it was more finely polished, more anatomically realistic, and the jaw was of a separate piece, removable from the rest of the skull. Otherwise, though, it was of almost the same exact shape, which fact had garnered interest in the object years earlier, when the anthropological journal Man published a 1936 article consisting of a morphological comparison of the Boban skull in the British Museum and this new skull, which the article indicated was in the possession of one Sydney Burney. After Mitchell-Hedges obtained the skull, he immediately began making unsupported claims about its age and the method by which it was made, saying in a letter to his brother that “scientists put the date at pre-1800 B.C., and they estimate it took five generations passing from Father to son, to complete.” Mitchell-Hedges kept this crystal skull in his possession for the next 16 years, until his death in 1959, and thereafter, it passed into the possession of his adopted daughter Anna Mitchell-Hedges. Since her death in 2007, it has been in the care of her widower, Bill Homann. The story of the Mitchell-Hedges skull is not one of dubious provenance. We know very little about where it came from. It apparently came into Sydney Burney’s possession in 1933 from an undisclosed source. Burney was a London art dealer. It makes sense that he would buy the object and then approach museums with his find in order to ascertain its potential worth, afterward putting it up for auction to the highest bidder. We have no reason to think he forged the item himself, but we do have good reason to suspect that it may have come from the same source as Boban’s skull, since analysis indicates they were carved according to the exact dimensions of the same skull. Whether Boban fabricated both of them or both were carved by some unknown forger, or the latter was copied from the former somehow, we may never know. The story of the Mitchell-Hedges skull is rather more interesting in the way that it gathered myth and legend through the years, like a snowball growing as it tumbles down a snowy slope, false claims accreting as it passed through the decades and through the hands of those who sought to profit from it. And it all began with Mitchell-Hedges himself, whose life story should have demonstrated his lack of credibility from the start.

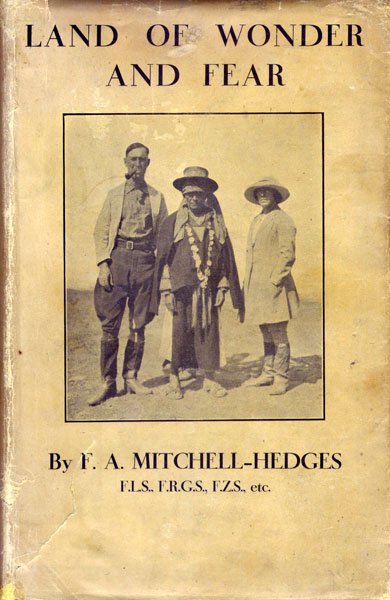

Frederick Mitchell-Hedges loved a big fish story…literally. He was a wealthy man who spent his time pursuing the hobby of deep-sea fishing, and capitalizing on his hobby by selling stories about his supposed adventures. The fish that got away in his stories, which he published in articles and books, were always giant, man-eating monsters, and Hearst newspapers paid him to spin his yarns. Soon his tales turned to fantastical pseudo-archaeological claims. He claimed to have discovered tribes uncontacted by civilization, to have found unknown continents, and to have been the first to explore the ruins of amazing lost civilizations. In 1927, he claimed to have been assaulted and robbed of some important anthropological artifacts, including papers and shrunken heads, but the Daily Express newspaper exposed this claim as a hoax. Mitchell-Hedges then tried to sue the newspaper for libel the next year, but he lost the suit and under cross-examination was revealed to be something of an imposter when it came to his claims as an explorer. In his 1931 book, Land of Wonder and Fear, he capitalized on these dubious claims, such as having discovered the Mayan city of Lubaantún in British Honduras, though archaeologists and European residents of the area protested that the ruins he had visited, by motor car, had been well-known for a long time. A few years after buying the Burney crystal skull in 1943, and immediately mythologizing it with claims that it was 2000 years old—far older than Boban had ever claimed his “Aztec” skull to be—he had changed his story and begun claiming that he had discovered it himself in the 1930s. Within another five years, he published a new book, Danger My Ally, in which he embellished the story of his crystal skull even further, claiming that it was 3,600 years old, and that somehow he knew it had been used by a Mayan High Priest for some occult ritual. “When the High Priest willed death,” he wrote, “with the help of the skull, death inevitably followed. It has been described as the embodiment of evil.” Thus the Mitchell-Hedges skull came to be called the Skull of Doom, which of course would have been a better name for an Indiana Jones film, if they hadn’t already made Temple of Doom. It seems possible that Mitchell-Hedges’s fictionalizing of the crystal skull’s paranormal powers was inspired by a piece of short fiction published in 1936 called The Crystal Skull. In this story, the author Jack McLaren tells the story of a stolen crystal skull that gives its wielder some kind of psychic powers. Whether Mitchell-Hedges read that story or dreamed up his tall tales on his own, this was just the beginning of the claims of supernatural or occult powers that would eventually surround the Mitchell-Hedges skull.

Mitchell-Hedges (left), as pictured on the cover of one of his books. Image courtesy Archaeology magazine.

The majority of the paranormal claims made about the Mitchell-Hedges skull and crystal skulls generally, were made after Anna Mitchell-Hedges had inherited the object. Like her adopted father before her, she changed the story of where the skull had come from, likely in an effort to provide some more credible provenance. Now she claimed that it was not Frederick Mitchell-Hedges who found it, but rather that she had found it herself when she accompanied him on a certain expedition to the lost Mayan city of Lubaantún. And in order to account for the well-documented fact that her adopted father had bought the crystal skull from London art dealer Sydney Burney, she later claimed that he had borrowed money from Burney and left the skull as security, that he’d merely put the skull in hock until he could redeem it. But of course, it had been auctioned at Sotheby’s, not bought directly back from Burney, and a letter about the skull from Burney to the American Museum of Natural History indicates that it had been in Burney’s possession for a full decade before it was sold at Sotheby’s. More than this, Anna Mitchell-Hedges’s story about finding the skull continually changed. She found it in 1924, or was it 1926 or ’27 or ’28? She remembered being lowered down into a cave, or was it the interior of a pyramid? Or rather, she had climbed to the top of the pyramid and found it under the stones of a fallen altar. And after all, eventually, she recalled that it had been her birthday when she discovered it. Odd that this would slip her mind for so long. Since other archaeologists who were at the Lubaantún site in 1927 and 1928 and asserted that neither Frederick nor Anna Mitchell-Hedges were there at the time, she eventually decided it must have been 1924, making her only 17 years old. The further problem here is that Frederick Mitchell-Hedges wrote extensively about his expeditions, and he did not mention bringing a 17-year-old daughter with him. He wrote about other women he brought, though. For example, he writes about his companion and the bankroller of his expeditions, Lady Richmond Brown, and he even mentions that his secretary, Jane, traveled with him. He even goes into great detail about bringing a pet monkey named Michael along, who became ill on the expedition and whom he had to shoot to put out of his misery, burying him with all the ceremony of a loved one. As scholar Jane MacLaren Walsh points out, it is certainly strange that he would devote more time to his secretary and his pet monkey than to his own teenage daughter in recording the events of the expedition, especially if it were she who had discovered a life-size crystal skull on her birthday. That, it seems, would certainly have made it into the book. Instead, in Danger My Ally, Frederick Mitchell-Hedges is coy about where and when he supposedly found the skull, saying only, “How it came into my possession, I have reason for not revealing.”

Once Anna had acquired the coveted Mitchell-Hedges skull, it wasn’t long before some former associates of her father came around to encourage her to profit from it. Specifically, Frank Dorland, an art dealer from San Francsico, convinced her that he could “launch a programme about the skull” that would raise its worth and drive up its potential price. Dorland had done this before for Anna father. In 1953, six years before his death, Frederick Mitchell-Hedges had purchased a religious icon that was likely one of many copies of a famed icon, the Black Virgin of Kazan. With Dorland’s help, though, Mitchell-Hedges had been able to promote his icon as the original Kazan icon, lost in 1904. Failing that, he asserted that it was at least a certain 16th-century copy of the original, the “Fátima image,” which was lost in 1917 and was just as sought after. Dorland continued his promotion of the Mitchell-Hedges icon for years after Frederick’s death, managing to get it exhibited in New York’s World Trade Fair in 1964. By that time, he had also contracted with Anna Mitchell-Hedges to promote the crystal skull, and he did so by amplifying the idea that it was a supernatural object. He took to calling it “The Skull of Divine Mystery,” “The Skull of Knowledge,” and “The Godshead Skull.” In documents sent to the director of the Museum of the American Indian, it was claimed that the skull could protect against the evil eye, that it “carries protection from heaven” and “defeats all evils of witchcraft,” claiming that it wielded “benevolent divine magic dealing with heaven and angelic forces.” The fingerprints of Dorland’s marketing of the skull seem apparent here, and after this, his “programme” seemed focused on getting books published that further mythologized the crystal skull as a talisman of occult power. In 1970, a book appeared called Phrenology, about the pseudoscience of studying the bumps on people’s skulls in order to determine their personality traits. But the book was more than a simple phrenology manual. It was written by Sybil Leek, a self-proclaimed psychic medium and probably the best-known representative of witchcraft in England. She wrote some 60 books in her lifetime, on astrology, numerology, faith healing, reincarnation, et cetera, and the cover of her book on phrenology pictured the Mitchell-Hedges skull. In it, she made strange claims that the skull was not actually Mesoamerican but had been carried to the New World by… and maybe you can guess who… that’s right, the Knights Templar. After this book’s publication, Anna Mitchell-Hedges was upset with Dorland, not so much about the claims Leek made in it, but rather that the English witch said the skull belonged to Frank Dorland. In order to pacify her, Dorland arranged for another book to be published by a novelist named Richard Garvin. This 1973 book, with the kind of eye-catching occult cover art that grabbed readers’ attention in those years, was called The Crystal Skull, and in it, it was suggested that the skull originated in Atlantis, that it was evil, that it brought death to those who would not revere it and could be used as a terrible weapon in the wrong hands.

The beguiling cover of the 1974 book that helped popularize the Crystal Skull legend. Image used under Fair Use.

So we see that the mythologizing of crystal skulls as objects of occult power started with the yarn-spinner Frederick Mitchell-Hedges, and continued after his death with his adopted daughter and with Frank Dorland, his old partner in marketing dubious artifacts. From the 1970s onward, it is possible to trace all outlandish paranormal claims about crystal skulls, including their ability to hypnotize and impart knowledge when one looks into their eyes, as depicted in the Indiana Jones film, back to these efforts at marketing an artifact that previously had only been viewed as a ritual object, if not as a fraud. In the book that Frank Dorland commissioned, the author insinuated that archaeologists dismissed it and scientists refused to study it “because they cannot come to grips with the fact that there may be a knowledge demonstrated here which is beyond our civilized comprehension.” And this, as usual, is the ultimate joke. As I have argued before, such claims just show a fundamental lack of understanding of the scholarly community and academic study and publishing, as a scientifically verifiable discovery of something seemingly supernatural would be sought after. It would mean fame, which would mean funding. And in fact, my principal source for this episode, the anthropologist Jane MacLaren Walsh, a Smithsonian archivist, has done more than dig up all the history of the crystal skulls, from Boban to Mitchell-Hedges. She has also subjected the Mitchell-Hedges skull to the scientific testing that it was long claimed scientists refused to conduct. What she found was that, indeed, the Mitchell-Hedges skull appeared to be an exact copy of the Boban skull in its dimensions, but that the anatomical details of its eye sockets, nasal cavity, teeth and jaw were more correct, which leads to the conclusion that a later forger was attempting to capitalize on the Boban skull while also improving on its workmanship. Using ultraviolent light, computerized tomography, and scanning electron microscopy, Walsh confirmed that the Mitchell-Hedges skull showed signs of having been carved with high-speed wheeled rotary carving using diamond-coated, hard metal tools that have only been available in modern times. Thus, the Mitchell-Hedges skull was likely forged sometime in the 1930s, before it came into Sydney Burney’s possession. Likewise, similar testing was conducted on the Boban skull that demonstrated it too had been carved using wheeled rotary technology that would have been in use in the 19th century. Considering this evidence, it is safe to dismiss all the crystal skulls as forged artifacts, and all the claims made about their provenance and paranormal powers as nothing but hoaxes.

At first blush, one might think that these hoax artifacts are a ridiculous MacGuffin for Indiana Jones to quest after, since as an archaeologist in the 1950s, when that film was set, he likely would not have given much credence to the stories of crystal skulls. But of course, if we were to judge his character based on the real-life authenticity of the objects he searches for, then the notion that he and his father believed the Holy Grail was a real object makes them seem just as ridiculous. Based on the idea that he thought the literary invention of the Holy Grail might have been real, and that he was obsessed with the Mitchell-Hedges skull, we might begin to view Indy as a credulous dupe and a pseudo-archaeologist. But we must remember that these are action-adventure films with science-fiction/fantasy elements, and for such a story, the crystal skulls are kind of perfect MacGuffins to weave into a story about the search for a lost city of gold founded by ancient aliens. Even though the execution wasn’t great, I suppose I see what they were going for and can’t fault them for trying. Interestingly, there is one more connection between the story of the crystal skulls and the Indiana Jones films. The golden idol that Indy snatches from a booby-trapped ruin in South America in Raiders of the Lost Ark is apparently modeled after a statuette of the goddess Tlazolteotl on display at the Dumbarton Oaks museum in Washington, D.C. The provenance of this statuette was questionable, and because images of this deity do not typically depict her in a squatting position giving birth, as is the case with this piece, some suggestions of its inauthenticity have arisen. As it turns out, Eugène Boban played a significant part in the original acquisition of this piece, and when Jane MacLaren Walsh, who was piecing together Boban’s frauds more than a hundred years later, analyzed the statuette, she again discovered evidence of modern rotary lapidary tools. Thus it seems more than one hoax artifact cooked up by the swindler Eugène Boban may have ended up inspiring the MacGuffins that famous archaeologist Indiana Jones risks his very life seeking out.

The Mitchell-Hedges skull. Image courtesy Archaeology magazine.

Until next time, when next you visit a museum, remember, even the objects displayed there and asserted to be of a certain age and origin, aren’t always as authentic as is claimed.

Further Reading

May, Brian. “Diableries: French Devil Tissue Stereos.” The London Stereoscopic Company, www.londonstereo.com/diableries/index.html.

Morant, G. M. “142. A Morphological Comparison of Two Crystal Skulls.” Man, vol. 36, 1936, pp. 105–07. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/2789341. Accessed 26 July 2023.

Walsh, Jane MacLaren, and David R Hunt. “The Fourth Skull: A Tale of Authenticity and Fraud.” The Appendix, vol. 1, no. 2, April 2013, theappendix.net/issues/2013/4/the-fourth-skull-a-tale-of-authenticity-and-fraud.

Walsh, Jane MacLaren. “The Dumbarton Oaks Tlazolteotl: Looking Beneath the Surface.” Journal de la Société des Américanistes, vol. 94, no. 1, 2008, pp. 7-43. OpenEdition Journals, journals.openedition.org/jsa/8623.

Walsh, Jane MacLaren. “Legend of the Crystal Skulls.” Archaeology, vol. 61, no. 3, 2008, pp. 36–41. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41780363. Accessed 26 July 2023.

Walsh, Jan Maclaren. “The Skull of Doom.” Archaeology, 27 May 2010, archive.archaeology.org/online/features/mitchell_hedges/.