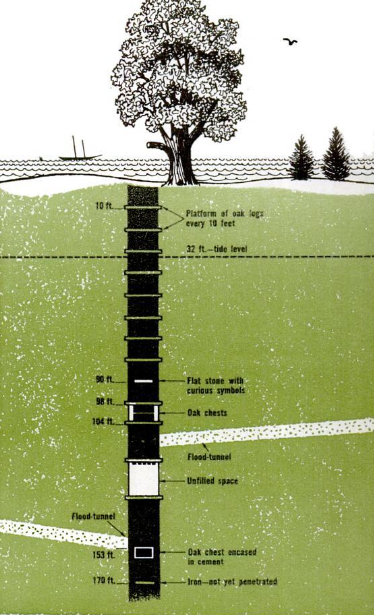

After the first newspaper articles recording the legend of Oak Island began to appear in Nova Scotia newspapers in the 1860s—or rather, perhaps because of them—interest in digging for treasure on Oak Island renewed. In 1861, another treasure company, The Oak Island Association, invested in the hunt. They made an effort to re-excavate the original Money Pit as well as to dig new shafts. During the course of their work, multiple wooden platforms they’d constructed collapsed, filling the bottom of the Money Pit with ever more lumber that later digs would encounter and believe was sign of some treasure chamber or chests. During the first year of The Oak Island Association efforts, the diggings claimed their first known victim when a boiler on a pump engine exploded, killing one treasure hunter. Still they worked on, attempting to dig down from the beach to cut off the theoretical flood tunnel, but failing, since, as was thoroughly discussed in the previous installment of this series, there is no flood tunnel. After that company dissolved in failure, another formed in 1866, The Halifax Company, and again failed to shut the nonexistent flood tunnels and found nothing but wood in the original shaft, surely just pieces of the some 10,000 board feet of lumber estimated to have fallen in during previous digs. The lure of the legend was dormant then for a time, but in the late 1890s, it returned when a new group of treasure hunters descended on the island. This group used a boring apparatus once more, and claimed to have brought up a piece of sheepskin parchment with the letters “vi” visible on it, written supposedly in India ink, a tantalizing find that would seem to indicate something old buried down below. Beyond this supposed find, however, no sign of a treasure was turned up. Instead The Halifax Company turned its efforts to proving the existence of a flood tunnel by pouring red dye into the pit, after which they found indications of the dye off a few different beaches. In reality, if this even occurred, they had only unwittingly disproven the claim about a flood tunnel from Smith’s Cove and proven that the diggings were flooded by a natural watercourse, through which the dye had been dispersed not just at the cove but into all the surrounding waters. This operation too resulted in the tragic death of one man, who fell into a shaft, and like all the others, ended in failure. In 1909, another group, which included Franklin D. Roosevelt among them, tried to find treasure on the island, and the endeavors of this expedition, which called itself The Old Gold Salvage Group, sounding kind of like a cash-for-gold outfit with a bad cable TV commercial, would later be recorded in a Collier’s Magazine article written by H.L. Bowdoin, a leader of the group. According to Bowdoin, he had seen the supposed inscribed stone and believed it had never been inscribed, and he had seen the scrap of parchment and believed it had not been brought up in the previous diggings. It would have been impossible, he said, for an auger to bring up parchment or even links of chain, for that matter, through 120 feet of water. Despite the fact that still nothing was found, and a leader of the 1909 diggings even came out in a national magazine to assert that “there is not, and never was, a buried treasure on Oak Island,” still the legend lured in others, and FDR was not the only well-known person to have taken an interest. Movie stars Erroll Flynn and John Wayne would each be involved in organizing or funding a treasure hunting operation on the island. Mostly, though, the digs were spearheaded by true believers, self-styled treasure hunters who abandoned their lives and careers after reading a fascinating article in the press about the island, thereafter dedicating themselves to finding the buried treasure there, often buying land on the island and moving there, making it the whole of their life’s work. After a 1928 article, two such men, William Chappell and Gilbert Hedden, came to live and work tirelessly on the island during the 1930s. They found nothing but a couple of axes and picks that were likely only further debris from previous digs. In the 1950s and ‘60s, it was the Restall family, whose efforts were described in the Reader’s Digest article that captured the imaginations of so many, and they truly gave their lives over to the obsession, for Robert Restall, his 18-year-old son, and two others perished in a shaft after the release of poisonous hydrogen sulfide fumes. There was nothing supernatural about it. The release of poisonous gasses happens when digging deeply underground. This was the purpose of the famous “canary in the coalmine,” to warn miners of such imminent dangers. Nevertheless, despite the commonplace nature of the danger, this tragedy spawned a further legend, that the treasure on Oak Island was cursed.

After the Reader’s Digest article appeared and the legend was spread to a wide audience, a number of later treasure hunters appeared, moving to the island and spending the better part of their lives doing nothing more than digging or even just poking around looking for things on the surface that they imagined to be signs for where they should dig. That’s right. By the later 20th century, people didn’t even know where they should dig anymore. So many boreholes had been dug on the island that the original money pit’s location had been lost. One such treasure hunter drawn to the island in the 1960s was Fred Nolan, and another was Dan Blankenship, who felt compelled to leave his life behind in Florida and run off to dig for treasure all his life. Both of these treasure hunters would leave their mark on the legend, but unsurprisingly, neither would find treasure. Blankenship managed to find U-shaped wooden structure offshore of Smith’s Cove, which he believed was part of the flood tunnel structure, but which was more likely part of the salt cooking operation it’s now thought that fishermen conducted on the island. As for Nolan, his lasting contribution was Nolan’s Cross, a series of boulders that he thought formed a cross if one connected the dots. Thinking it an “X marks the spot” situation, he dug beneath the center and found a rock that looked vaguely facelike, which he imagined had been carved, but which really just looks like a boulder. According to legend, the cross formed by the boulders Nola found was perfectly symmetrical, though if you look at the diagrams that they use even on shows like the History Channel program, it’s manifestly cockeyed. The fact is that a land survey in 1937 marked numerous boulders and piles of stone on the island. True believers have had to continually expand Nolan’s Cross, suggesting it was a triangle or some other shape. With so many boulders on the island, it has now become a kabbalistic tree of life in the eyes of some, with some 10 or 11 rocks they think were purposely placed there. Even as late as 2010, Dan Blankenship was finding more supposed landmarks and showing them to CBC reporters. The CBC long took an especial interest in Dan Blankenship. Before the History Channel program, he was certainly the most media savvy proponent of treasure on the island. Back in the 90s, he was telling them about a new hole he intended to dig if he could get the financing, swearing it would be his last effort. It wasn’t. And before that, in 1970, only five years after he’d come to the island, he got the CBC to come out and put a camera down one shaft he was working on, into muddy waters, and in the murky and indiscernible footage that came back, he swore you could see not just tools like picks, but also treasure chests, and even the skeletal hand of some human remains. Looking at the grainy video today, all that can be seen are vague mud covered shapes, and a piece of wood that is likely just debris that had fallen into the diggings. Every such find is easily explained as their imaginations running away with them, thinking “maybe these rocks line up,” “does that boulder look like a face?,” and “pause! Enhance! Is that a treasure chest in this completely indiscernible film footage?”

Dan Blankenship, at work on the island.

Now, since the premiere of the History Channel program in 2014, we have the Lagina Brothers, Rick and Marty, a retired postal worker and former petroleum engineer, respectively, who like so many before them were inspired as children by the Reader’s Digest story on Oak Island. Also like so many before them, they sought some investment, figuring out a way to get paid even if they didn’t find any treasure. Taking Blankenship’s lead, though, they saw the interest that the media and the public would take in their project, so rather than financers seeking a stake in the treasure, they pitched a television program that would keep them in money so long as they could keep the dig going and keep up viewer interest with consistent tantalizing finds. In fact, the money they would make from their reality TV program would taper and cease if they were ever to actually find the treasure. After a while, if one were to commit the masochistic act of actually watching it, it’s very clear that those involved are just stringing the viewer along. Each season they start focusing on some other geographical feature of the island. It’s no longer about the Money Pit and the flood tunnels to the beach. Now it’s about the stone landmarks, and a swamp that is vaguely triangular in shape, and a field of boulders that is in a “quadrilateral” shape. Of course, a quadrilateral is not a regular shape; it’s an odd shape with four sides, but they clearly want to keep with their theme of finding imaginary geometrical patterns on the island. Beyond just rocks and swamps, they have turned up a few genuine artifacts. They discovered a jeweled brooch, a silver ring, a lead cross, a silver button, iron blacksmith tools, and a few coins. However, all of these were found on the surface, not hundreds of feet below ground. They are no more impressive than the findings of many a metal detectorist. There have been claims about the dating of these objects, that the button and ring are from the 18th century, the blacksmith tools dated to the 14th century, and that one of the coins was a Roman coin. Even if these were all true, it must be remembered that the island had been inhabited for centuries, and the objects could have been brought to the island at any time. What many seem not to realize is that for any such artifacts to be meaningful, they would have to be uncovered in an undisturbed archaeological site, by archaeologists who carefully document the context of the find. Without such scientific method, an artifact is just something that might have been brought to Oak Island as a hoax.

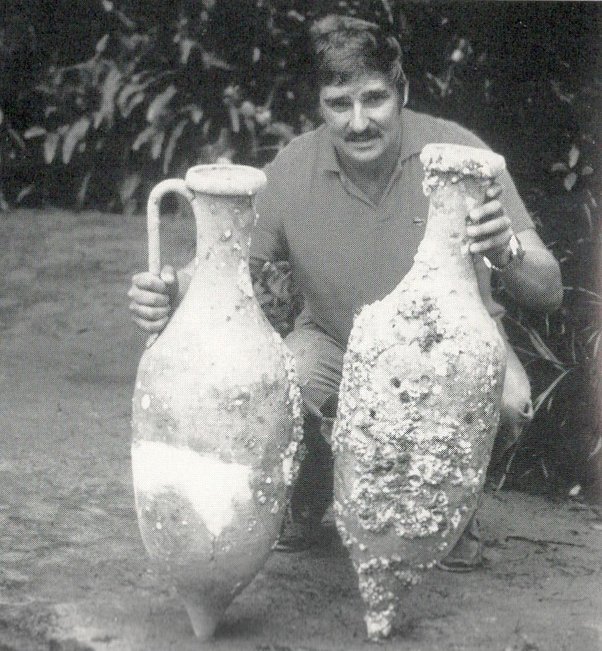

A perfect example of this occurred in 2015, when it was claimed that a fisherman had discovered a Roman sword, not on, but near Oak Island, while out scalloping. It was claimed that this fishermen had found the sword years earlier and fearing some legal reprisal for having illegally recovered a historical artifact, had been secretly keeping it, until he decided to bring it to the producers of the History Channel’s Oak Island program. And one odd character who had appeared on the program previously, J. Hutton Pulitzer, who calls himself a “Treasure Force Commander” and wears a wannabe Indiana Jones outfit, vouched for the sword, saying he had personally confirmed its authenticity with scientific testing. If such a find were true, it was argued that it proved claims about ancient Roman mariners having crossed the Atlantic in antiquity, reaching the shores of the Americas. But as I discussed in my previous series, there have been a few hoaxes perpetrated as evidence of ancient Roman contact with the Americas, including the Tucson artifacts and the fake Roman amphorae sunk in a bay near Rio de Janeiro. And even if the sword were authentic, the lack of provenance, the lack of evidence regarding the context in which it was found, means that it could just be an authentic artifact brought to Oak Island in the modern day. However, the strange design of the sword, which featured a carved Hercules figure as its handle, which would be a very awkward handle indeed, put skeptics on guard, and a few began to write about this, including Jason Colavito and archaeologist Andy White, who is known for exposing pseudoarchaeology. As “swordgate,” as the scandal was thereafter dubbed, unfolded, more and more such swords, struck from the same mold, were brought to light, and analysis of these swords, as well as the one supposedly found near Oak Island, proved they were nothing but modern souvenirs, produced to be sold to tourists outside Pompeii, and that the molds were used to forge numerous other fake Hercules swords. But Commander J. Hutton Pulitzer would not relent. Though even the History Channel program declared it a modern object, he suggested that there was some cover-up. He rallied his social media followers to harass skeptics who questioned him. He threatened legal action against his debunkers and encouraged conspiracy theories that they weren’t even real people. Naturally, Pulitzer himself became a figure of interest to these and other skeptics. His name is actually Jeffry Philyaw, a former marketing guy who rebranded himself numerous times, first as an inventor, next as an entrepreneur, then as a treasure hunter, and most recently as an election integrity expert. His invention, the CueCat, a cat-shaped handheld device for scanning barcodes that would pull up webpages, had been a widely ridiculed failure and the reason for changing his name. His entrepreneurial venture was selling bottled rainwater and was likewise a failure. And after his ignominious treasure hunting career, he most recently appeared in the public eye making false claims about hacking the Georgia voting system, supporting former president Trump’s lies about election fraud. To the History Channel’s credit, they declared the sword modern, but Pulitzer’s presence on the program before the sword’s appearance itself demonstrates the program’s lack of credibility, as well as how cranks are drawn to the legend of Oak Island, fully prepared to endorse hoaxes in order to support their own wild theories.

The fake Roman sword found near Oak Island.

Certainly the myths and crank notions that some try to attach to the Oak Island legend are many. Though the History Channel program was honest enough to admit that J. Hutton Pulitzer’s Roman sword was a fake, they also heavily featured his baseless speculation that it was the Ark of the Covenant buried in the Money Pit. And while Pulitzer favored the notion that ancient mariners had brought this treasure across the Atlantic from the Holy Land, others have claimed that later mariners did the same, more specifically that the… dun dun dunnnn! Knights Templar brought treasure they had unearthed from the Temple Mount across the ocean to Oak Island. Now I’ve erected some scaffolding here, so I need not refute the entirety of this legend. In the previous series I already examined, in detail, the idea of Templar persistence after their order’s suppression as well as claims about escape from France with treasure, or escape to Scotland, and their supposed connection with Henry Sinclair, whom some speculate crossed the Atlantic. None of it is convincingly supported, not their persistence, nor their escape with treasure, nor any presence in Scotland, nor any connection with Sinclair, and neither is there any support for the assertion that Henry Sinclair undertook a trans-Atlantic voyage. In a recent patron exclusive, I further examined and refuted unsupported claims that Templars learned of a star called Merica that ancient mariners had recorded would lead them to a land called La Merica. It’s all based on sources that were imaginary, or at least that we have no reason to believe really existed, appearing only in the breathless fantasies of pseudohistorians. And yet the History Channel’s Oak Island program promoted these myths time and time again. The boulders Fred Nolan thought were arranged in a cross? Must be a Templar cross. The lead crucifix found on the island? Another Templar cross, though it is not the flared Templar cross symbol they wore on there mantles, and thus is just a cross. On one old and weathered coin they found that is too beaten to be identified by numismatists they claim can be discerned a Templar cross, and it can sort of be seen, I think. But this does not make it a Templar coin, as they claim. In fact, Templars did not mint their own coins. Any coins closely associated with their order in the Holy Land would have been issued in the name of the King of Jerusalem, not in the name of their religious order. And the simple fact is that the cross seen on the coin, which is so often called the “Templar cross” is actually just the cross patée, or “footed cross,” in that its arms were narrower in the center and curved out to broad ends. It is perhaps better known today as the Iron Cross of the German Empire. This cross or a variation of it, like the footed cross potent, appeared on numerous coins, including Spanish and Portuguese coins. So even if that is a footed cross on the coin found on Oak Island, it’s really only of interest to rare historical coin collectors, not Templar historians.

Equally unsupported are the claims of Templar infiltration of Freemasonry. It is a striking parallel to the later unsupported conspiracy claims about the Bavarian Illuminati infiltrating Freemasonry, except for the very important fact that Freemasonry as we know it did not exist at the time of the Templar order’s dissolution. Imagined connections between Templars and Scotland have led to speculation about the Sottish Rite of Freemasonry being Templars in disguise, though it must be remembered that Templars were comprised mostly of French-speaking soldiers, who certainly would have stuck out in medieval Scotland, and the lodges of speculative Freemasonry, the kind we think of today with their odd rituals and leisurely gentlemen memberships, didn’t appear until four hundred years after the Templars were suppressed, in London, not Scotland. The Scottish brand of Freemasonry would only appear some twenty years later, as close as we can reckon based on the first mentions of it. It spread because of how popular Fremasonry became in that era. But conspiracists will say Nova Scotia means “New Scotland,” so it must be Masonic, though Scotland is not synonymous with Masonic. And they’ll say that since the early Nova Scotia councilmen were Masons, this shows that Nova Scotia had a Masonic government, but the fact is that many civic-minded men of that era were in Masonic lodges as it was simply de reigueur. As for Oak Island, conspiracists point to the supposed inscribed code on the stone found in the pit, which as I’ve said may never have existed or if it did may not have even been inscribed, and claim it may have been a Masonic code. Or they look at the supposed landmarks on the island for geometrical patterns they can discern as Masonic. Interestingly, skeptics too see a Masonic connection here, but not one that suggests there really is anything buried on Oak Island. Renowned skeptic Joe Nickell, examining the story of the Money Pit’s discovery as it appeared in 1860s newspaper accounts, has pointed out that multiple aspects of the tale, the presence of the three boys seeing signs and discovering the hiding place, matches in key regards with the Masonic allegory of the Secret Vault, in which three sojourners discover a secret crypt into which King Solomon had deposited secret wisdom, an allegory used in the initiation ritual into the Royal Arch degree of Freemasonry, typically granted to three initiates at a time. Nickell’s point, of course, is that the whole story might have been a winking prank, meant only to be understood by other Masons reading the newspaper, perhaps indicating only that McInnis, Vaughn, and Smith had received the Royal Arch degree. Despite his conclusions, though, Nickell’s observations only pour fuel on the fire of conspiracism, as theorists suggest that these parallels only mean Masons are responsible for hiding some kind of treasure on the island.

One such coin featuring a cross patée, a denier, typically called a “Crusader coin,” depicting King Bohemond III of Antioch on the opposite side, and having no particular connection to the Knights Templar, who were just one of many groups of Crusader knights.

There is no shortage of theories regarding who buried something on Oak Island and what that something is. One version was that the British had hidden their soldiers’ payroll there during the revolution, a theory that can be superficially supported whenever some old colonial era button turns up. Dan Blankenship liked the rather mundane notion that some rogue Spaniards had stashed some of their loot before heading home, thinking to keep for themselves some of the treasure meant for royal coffers. Of course, when a Spanish coin turned up, it was claimed as evidence for this theory. According to some reports, Franklin Roosevelts group favored the idea that Marie Antoinette’s jewels had been buried on the island, smuggled out of Versailles by a lady-in-waiting, according to an apocryphal story. So when a brooch turned up on the island, it is touted as proof of this theory. One really outrageous theory is that the original manuscripts of Shakespeare’s plays await discovery deep beneath Oak Island, and the bit of parchment supposedly—but not really—discovered underground was confirmation of it. This ties in with claims about the authorship of Shakespeare and the idea that his plays were actually written by polymath Francis Bacon. Simple logic would tell us it would be absurd for such lengths to be taken to hide manuscripts of some comedies and dramas, even if they were originals that somehow revealed their true authorship, because who would have cared that much about it? But conspiracists bend over backward, suggesting that Francis was a Rosicrucian, that he wrote codes and hints into Shakespeare’s plays, that these clues lead to Oak Island, on which he buried not his plays but rather other ancient documents and manuscripts of great importance, and that he devised the cipher on the inscribed stone himself. But remember, there is no evidence that any cipher ever really was inscribed on the stone, as extant drawings of it appear to be fake. Also recall that the piece of parchment supposedly turned up probably never was. H.L. Bowdoin, in his Collier’s Magazine piece, after stating that no auger could pull up a scrap of parchment through 120 feet of water, also says that the scrap of parchment was not found at first, when soil samples were examined, but only later, implying it may have been planted as a hoax. While all of these spiraling conspiracies and tall tales are manifestly incredible, we must remember that the legend of Oak Island has always relied on a fantastical story. It all started with the original tall tale of buried pirate treasure, specifically the treasure of Captain Kidd.

The legend of Captain Kidd’s buried treasure animated many a treasure hunter in the New England area for more than a century. Ironically, as more and more has been learned about Kidd, it has become clearer that Kidd did not bury vast caches of looted money, as had long been thought. William Kidd was a character shrouded in myth for a very long time. Though he started as a privateer and pirate hunter, he became viewed by many as a vicious pirate and murderer himself, leading eventually to his trial and execution. But he may have received a bad rap. As a young man he had apprenticed aboard pirate ships crewed by both Englishmen, like himself, and Frenchmen, and after participating in a mutiny, he became a ship captain. But despite whatever piratical adventures he was involved with in his youth, he made his name fighting against the French in the Nine Years War, not only in the Caribbean but also off the coasts of New England. He was an active member of society in New York City, helping to finance the building of Trinity Church and marrying a wealthy widow. In 1695, he left on his final voyage, to hunt pirates and French warships under a letter of marque signed by King William III of England, but almost immediately he began to earn a bad reputation. When his ship encountered a Navy yacht, his crew didn’t salute them but rather slapped their backsides instead, and in retaliation, the Navy pressed a large number of his crew into service, even though this was illegal since his letter of marque excluded them from impressment. Indeed, this would not be the first time that the Royal Navy would attempt to force his crewmen into service, and at a later date, Captain Kidd resolved the matter by promising to deliver the men but leaving port in the middle of the night. Thus among the Royal Navy, he began early in his final voyage to take on the reputation of a pirate. Kidd’s voyage, which would take his ship all the way around the Cape of Good Hope to the Indian Ocean, where pirate ships preyed on the rich merchant vessels of the Mughal Empire, would be troubled by disease and rumblings of mutiny. Having not encountered any prizes they could legally take, one gunner urged Kidd to attack a Dutch ship, which would have been illegal. When Kidd refused, the sailor reportedly cursed him and made some mutinous remarks, whereupon Kidd struck him on the head with a bucket. The sailor died the next day, and this incident would later come back to haunt Kidd.

A depiction of Captain Kidd as a gentleman privateer, aboard his ship in New York harbor.

Despite what later legends would claim, Captain William Kidd was not very successful in taking prizes during his voyages in the Indian Ocean, but he did take a couple of merchant ships, and he took them legally, for they sailed under the protection of the French, and Kidd kept the sea pass documents to prove it. However, because the captain of one ship was English, and because the cargo of another belonged to an official in the Mughal court, and because the political tides had turned against Kidd back in England, he was officially declared a pirate, and English men-of-war were dispatched to hunt him down. In 1698, the Piracy Act kicked off a campaign to arrest and prosecute pirates, but it also presented the possibility of a royal pardon to pirates who turned themselves in. However, Captain Kidd was explicitly excluded, so when it became clear that he had no choice but to turn himself in, he felt he had to take precautions, hiding one of his prizes and burying his loot. This is the origin of the buried treasure legend. While it’s true that Captain Kidd did bury some of his looted goods ahead of his arrest, the legends have inflated how much he buried and what he buried. In truth, the bulk of what would be considered treasure that he took from his meager prizes was composed of sugar, opium, and fabrics like silk, not gold and silver. And it is even known where he buried it: on Gardiner’s Island, near Long Island. This cache was soon afterward found and taken to England as evidence in his trial. Kidd found that even his former allies had turned against him, as he had become an embarrassment. At his trial, he was surprised to find he was charged with the murder of his crewman with a bucket, as ship captains were typically granted much leeway regarding the discipline of crewmen and mutineers. And when it was asserted that his capture of a certain ship was an act of piracy, he discovered that his evidence, the sea passes that proved the ship was sailing under French protection, had been conveniently lost. Kidd was hanged, twice because the first time didn’t do the trick, and afterward his corpse was gibbeted, hung in a cage over the River Thames as a warning to pirates. Throughout the 19th century, though, legend of his buried treasure would continue to animate many treasure hunters and serve as the foundation for many buried treasure legends, including the earliest claims about Oak Island. In the 20th century, though, the documentation that could have exonerated Kidd was discovered, showing he was more privateer and pirate hunter than pirate, and in 2007, the wreckage of the merchant ship he had hidden away was discovered near a small island off the coast of the Dominican Republic. Underwater archaeologists assert that there is no sign that the wreck had previously been looted, and yet there was also no treasure aboard her beyond historical artifacts, like a cannon. That’s because Kidd was likely not so rich in treasure as legend would claim, and most everything he hid away was likely soon after recovered, if not by authorities, as has been asserted, then by the pirates who helped him bury it.

In the absence of fact, however, legend flourishes, and there are always characters who will take advantage of that. With the rumors of Captain Kidd’s treasure so popular, a new class of treasure-hunting mystics arose in New England and all up the North Atlantic coast, including in Nova Scotia. These men presented themselves as magicians, or rather, seers. Some of the earliest of them claimed to be able to find buried treasure with dowsing rods. These are the witch hazel rods often said to be capable of finding the location of water underground. So-called “rodsmen” would help farmers find the best spot to dig a well, and before long, they were also helping to find buried treasure. However, according to these mystics, the treasure Captain Kidd or Blackbeard or whoever had left behind was not so easily obtained. Actually, these treasures were cursed, they claimed, guarded by the spirits of dead pirates, or perhaps demons or witches or other spirit guardians, and if certain mystical rites were not followed exactly, such as the drawing of magic circles and symbols around the site, and the sacrifice of an animal offering—if these and other requirements were not met, the treasure would actually be spirited away, moved underground to some other location. People really believed this nonsense, and we know it because there exists a wealth of documentation, much of it in the form of legal proceedings, as these treasure hunters were considered disorderly persons, scamming those who helped them dig. Many of these treasure hunters were known counterfeiters; they would bury their bogus moneys and pretend to find it as a form of money laundering. But once you had earned a reputation, by this or some other means, of being able to find buried money, you no longer needed to actually find anything. The way the scam worked was you would collect investment funds, get sacrificial livestock donated that you could afterward use for meat, and collect actual money from those whom you promised a stake in the treasure. Then you would make claims about magic circles and digging only at night, and declare that no one must utter a word within the circle, lest it wake the treasure’s guardian. Then all they had to do was wait until some impatient digger broke the rule, voicing their frustration, or until the morning light came, and they could claim the dig had failed and the guardian had whisked their treasure away. This may seem absurd, but it’s true. We know it’s true because of documentation preserved specifically because it is of interest to Mormon scholars. You see, Joseph Smith, who would later go on to found Mormonism, used to be one of these treasure hunting scammers. He came from a family of rodsmen, and eventually he would claim to be in possession of a seer stone, a little rock that showed him where buried treasure was. Joseph Smith too would be prosecuted for his treasure hunting frauds, and eventually, he would make a different claim, that he had discovered inscribed gold plates and that his seer stone allowed him to translate them, thereby composing the Book of Mormon and transitioning from treasure-hunter to prophet.

The tools of Joseph Smith’s mystical treasure hunting trade, including drawings of magic circles and a ceremonial dagger used in his treasure hunts.

What does this have to do with Oak Island, you might be asking? Think it through, and you’ll see that it leads us to the most logical and rational explanation for what’s really behind the legend of a cursed treasure on Oak Island. Like many of the treasures that con men claimed to be leading digs to find, it started as a claim about pirate treasure, even specifically Kidd’s treasure. The legends about Captain Kidd’s treasure would inspire many a popular fictional story, like Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Gold Bug” and Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island,” and the original stories about the treasure’s discovery, about three boys finding signs of buried treasure on an island haunted by pirate ghosts, bear a suspicious likeness to these popular tales, which were often about children and featured the ghosts of pirates. Likewise, treasure hunting scammers typically kept stringing their diggers and investors along by pointing to any little thing they might find in their diggings, like a piece of wood or an odd stone, claiming it was a sign or “mark” that they were close to the treasure or on the right path. Joseph Smith’s seer stone itself was a stone that was turned up in a well digging that he claimed had supernatural faculties. And likewise, the tales of the tackle block in the tree, the depression on the ground, the pick marks in the pit, the wooden platforms, the inscribed stone…there is no evidence that these existed, but they are just the sorts of telltale marks that treasure-hunter scammers would claim. And they would always be just about to get the treasure when something would go wrong and the guardian would prevent their discovery. Think of the claims about being just near the treasure chest when the flood tunnel filled the pit. Indeed, this is what has made the Oak Island legend have lasting power. Rather than a story of demons and spirits guarding buried treasure, it’s the equally false claim that a flood tunnel booby trap is what prevents the treasure from being recovered. This lends the tale more believability in the modern world, but at its heart, the scam is the same. Go back to the original 1860s newspaper articles, and specifically The Oak Island Folly, and we see that it’s a story of investors losing money in the venture because the promised treasure is never found. Yes, this is what makes the name “The Money Pit” so ironic, because it’s just a sinkhole into which people throw their money and never get anything back, but when we start to see that this is by design, it takes on ever starker meaning. The Onslow Company. What was that but a treasure dig based on a false claim, in which Simeon Lynds, the Nova Scotian who it was said organized it, was either scammed himself or was the scammer of his investors. And the same can be said of the Truro syndicate later and perhaps the Oak Island Association and the Halifax Company. Each dig coming oh so close, supposedly, to getting that treasure, but only uncovering supposed signs of it—the platforms, the inscribed stone, the gold links, the parchment scraps—only to be stymied by the guardian of the treasure, the flood tunnel. But where they had failed, perhaps the next company would succeed! And you could have a share of the treasure too for just a small investment in the operation.

So it begins to look like, at its heart, it was only ever a kind of Ponzi scheme. As time went on, even the organizers may have been true believers and dupes of the legend, but it is still only a scam, and the presence of known scammers like J. Hutton Pulitzer attests to this fact. Today, the most recent group of investors to be scammed have been the audience, who invested their time and imagination in the History Channel program. I have no doubt that History Channel programmers, and perhaps even the Lagina brothers themselves, did not believe that a treasure would be found on the island, but they still sold it to viewers every week and enjoyed the financial rewards it brought for 11 seasons. Just like the treasure con men of yore, they pointed to every rock and piece of wood as a sure sign they were on to something, and they filled their investors’ heads with all kinds of fanciful stories of treasure, and each season, each episode, they left on a cliffhanger, pretending they were right on top of that treasure, tune in next week to see them finally dig it up. It’s an age-old scam, and it works, so long as no one really thinks too hard on it. If one does, as we’ve seen, there are countless ways the legend falls apart, but the most fundamental problem, lying at the bottom of the Money Pit like bedrock, is the simple flaw in the logic of the entire conceit. If treasure of any sort were buried on Oak Island, first, it would not have been so elaborately buried. This has been pointed out already, that the excavation of slender, narrow flood tunnels from Smith’s Cove to the Money Pit would have required moving all the earth between the cove and the pit. Perhaps such a narrow channel could have been dug by a small burrowing animal, but not humans with crude hand tools. And the cove was not even the closest shore to the pit, so it would not have made sense to tunnel or drill horizontally in that direction. Not to mention what a feat it would have been to dig so deeply and set up the wooden platforms. We must remember that even according to the legend, diggers with hand tools could only get so far before they had to rely on horse-driven augers to drill more deeply. And today they rely on modern coring drills. Are we really to believe that 16th century seamen or ancient mariners were able to accomplish this without such equipment? Beyond that, why would they need to bury their treasure so deeply and elaborately on a deserted island? This is never adequately explained. Why not just bury their chests 20 feet down, as would be perfectly sufficient to hide anything. Nor is it ever explained why they did not return for their treasure. Surely if they took such efforts to hide it they would have come back for it, even if one or several of them had died or was arrested or was otherwise detained. Surely a recovery effort would have been mounted within the lifetimes of those who had buried treasure there. And let’s imagine what that recovery would look like. If it were true that the treasure was somehow buried so deeply below ground that modern equipment was needed to get to it, and whenever you came near it a booby trap filled the diggings with water, preventing any access to it, then how could they have hoped to recover it themselves? If the legend is to be believed, then treasure was not buried on the island, it was destroyed there, made impossible to recover.

There is a term, coined by skeptic Mark Hoofnagle, called “crank magnetism.” It is the idea that belief in one fringe idea, like pseudoscience, conspiracy speculation, or pseudohistory, leads to belief in others, because crank ideas attract each other. Dr. Hoofnagle uses this concept when describing denialism, for example, which often must resort to claims of conspiracy in order to make its claims. But we see this phenomenon all over the place. It’s why QAnon has exploded into a dozen conspiratorial directions, and why believers in the lost Tartarian Empire have been led inevitably to belief in giants. It’s why the Knights Templar and Atlantis always pop up, as we have seen again and again. It’s no mystery, then, why the old legend of Oak Island, a pretty simple pirate treasure story likely used to dupe unsuspecting investors into a treasure hunting scheme, has become so insanely vast in its conspiratorial implications, with ancient Roman contact with the Americas, hidden religious artifacts, Templars and Rosicrucians and Masons all figuring into its legend. The cult of treasure hunting in old New England always relied on fantastical ideas to fire the imaginations of those who would pay to search for treasure. This tendency of mystics claiming in this region to be capable of supernatural insight would lead to a great many other dubious beliefs. Joseph Smith parlayed it into an extremely successful modern religion. And not far from where Smith got his start, the Fox Sisters would pull off something very similar, claiming through ritual and paranormal faculties to be able to interact with the spirits of the dead, and thereby fooling the world into the very popular belief in spiritualism. When viewed in this perspective, the belief in a cursed treasure has led, in the past, through crank magnetism, to a variety of massive frauds and delusions. It should be no great surprise, then, that one treasure fraud, that of buried treasure on Oak Island, would survive the old scams, and through the accretion of numerous complementary legends and myths, promoted on bad cable reality TV and in the darker corners of the internet where conspiracy delusion and pseudohistory thrive, would become a modern myth whose perceived mystery many have devoted and lost their lives to solving.

Further Reading

Bowdoin, H. L. “Solving the Mystery of Oak Island.” Colliers, vol. 47, no. 22, 19 Aug. 1911, pp. 19-20.

Joltes, Richard. “History, Hoax, and Hype: The Oak Island Legend.” Critical Enquiry, 2006, www.criticalenquiry.org/oakisland/index.shtml.

White, Andy. “Swordgate” [category]. Andy White Anthropology, https://www.andywhiteanthropology.com/blog/category/swordgate.