The Oak Island Scheme - Part One: The Legend of the Money Pit

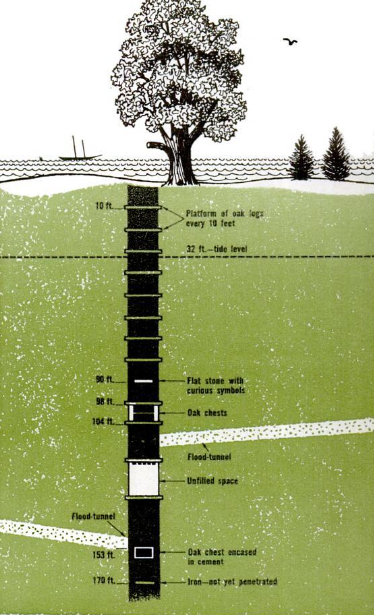

In January 1965, The Rotarian, official magazine of the Rotary Club, published a curious article by one David MacDonald relating a somewhat obscure tale about buried treasure in Nova Scotia, called “The Strange Case of the Money Pit.” In it, he relates a story a little uninhabited island in Mahone Bay called Oak Island, shaped “like a question mark,” said to have formerly been haunted by pirates, and about three children in 1795 who supposedly discovered signs of buried treasure there: a piece of ship’s rigging hanging from a tree above a clearing with a depression in the ground. As they dug up the spot, they found further indications that something was buried there, including wooden platforms every ten feet, and the article showed an illustration, bringing this Money Pit vividly to life. Though the boys failed to reach any treasure in their dig, their story inspired future treasure seekers, and in the early 19th century, a more well-funded excavation renewed their efforts, finding further indications of buried treasure nearly a hundred feet below ground, including a stone that was said to be inscribed with a message indicating that millions of pounds of gold were buried not far below. Before they could reach this promised booty, though, their pit flooded with water, and despite all efforts to bail it out and continue digging, they were sunk, so to speak. Almost fifty years later, some of the surviving boys brought in a syndicate and financed a third dig with more sophisticated machinery, such as a horse-driven auger that would drill down and draw up material it cut through, and during the course of their boring, they claim to have entered some kind of vacuum, like an empty chamber, and then to have drilled through wood and metal, suggesting they had cut into what sounded like loose metal. They believed they had drilled into treasure chests, and as proof, their auger brought up three golden links of a chain. Realizing that their shaft was flooding with salt water and rising and falling with the tide, they searched a nearby beach and found structures they identified as box drains that lined up with their dig site, suggesting that their Money Pit was not just naturally filling with water. No, it was booby-trapped with manmade flood tunnels, and the colorful diagram in the magazine piece illustrated these as well, to give the reader a clear picture of what even the men themselves could not see. Though the syndicate also failed to find their treasure, local fame of the potential find grew, and decade after decade, further attempts were made, each with its further tantalizing discovery to draw treasure-hunters on. One group in the 1890s put red dye into the flooded pit and claimed to have mapped the flood tunnels by finding where the red dye emerged into the sea. During this time, treasure hunters also claimed to have brought up traces of gold and a scrap of parchment bearing India ink through core drilling. Another group that included Franklin D. Roosevelt made a failed attempt to find something there in 1909. Further efforts are described in the article through the 1950s, each group spending tens of thousands of dollars and coming away empty-handed. But David MacDonald had truly struck gold in telling the tale, as his article was condensed and reprinted that month to a wider national audience in Reader’s Digest. After that, it became something of a sensation, appearing in numerous books and tv series about mysteries, and becoming the subject of more than 50 books that focus solely on the Oak Island mystery itself. This was the real treasure to be had, and the History Channel seized it, producing a reality TV program that followed the latest team of treasure diggers to descend on the island, the Nagina brothers. That 2014 program, The Curse of Oak Island, ran for 11 seasons and still has not officially been cancelled, though they too have never turned up any treasure. Surely, though, with this long history of claims and so many publications and docuseries examining and researching the story, there must be something to it, right? …right?

Considering the nature of the stories I tell in this podcast, and the topics I research, I often find myself using the words “legend” and “myth.” Sometimes it may seem that I use them interchangeably, but there are in fact important differences in their use. Both are used to refer to traditional stories or popular beliefs that have developed about someone or something. Additionally, both myths and legends are typically viewed by those who transmit them as ostensibly historical; they are traditions recounting things that supposedly really happened in the past, even when they may seem manifestly fictional or fantastical, as is the case with most ancient myths. While there is an alternative definition of a myth as “an unfounded or false notion,” a sense in which I also often use the term, this does not mean that all ancient mythology is entirely false or fictional, as many may have some factual basis, which I mentioned in the previous episode with regard to the person to whom King Arthur myths may refer. However, because the word “legend” more specifically denotes a story “regarded as historical although not verifiable,” we might more accurately refer to Arthurian legend, rather than myth. One further connotation, however, is that myths refer to more ancient stories of this kind, whereas legends are “of recent origin,” making them kind of myths in the making. When it comes to the story passed down to us about Oak Island, then, while I am tempted to call it a myth because elements of it have been credibly debunked and because the weight of evidence indicates that the idea there is even a treasure there is false, nevertheless, because it is of relatively recent origin and some parts of it may not be entirely made up, I think calling it a legend is more accurate. Now some listeners may think the 1700s, when the story began with the Money Pit’s discovery, and the indication that its purported treasure must have been buried a century or more before that, makes it old and “historical” enough to consider it myth, but in the grand scheme of things, especially when it comes to myths and legends, that simply wasn’t so very long ago. Less than 250 years have passed since the clearing in the woods was supposedly first identified as the location of buried treasure. Because of the discoveries said to have been made at the pit throughout the 19th century, some listeners may presume that there must be strong enough evidence supporting the claims about the Money Pit that we might move this story from legend into the more rarefied realm of a “historical mystery,” but in that they may be surprised. In reality, there is no historical evidence that any part of the legend occurred as claimed until the mid-19th century. There is a lack of primary source documentation to confirm the story of the site’s discovery and the first several digs. All we have are stories passed down after the fact, repeated without confirmation, and that firmly places this into the realm of legend.

The Reader’s Digest story that transformed a local tale into an enduring legend.

As no treasure has ever been found, and only guesses and fictional stories have been put forward about who supposedly visited this island in the past and buried something there, the start of the story, which me must examine first, is the tale of three boys who discovered something. The names of these boys are given as Daniel McInnes, Anthony Vaughn, and Jack Smith, and already we can find some discrepancies in the spelling of McInnes’s name, sometimes spelled with an “es,” and sometimes with an “is,” sometimes with a “G” as in McGinnis. In MacDonald’s Rotarian article and in other versions of the tale, the boys are said to have paddled over to the island in boats, and there are intimations that the island was entirely uninhabited. Indeed, it appears that legends of phantom lights and ghosts prevent mainlanders from even venturing out there, something that frustrates the boys’ efforts to get help in digging up their pit. The boys are said to have noticed a ship’s pulley on a tree branch. By the time of the Rotarian article, it’s said that this tackle block was on a sawed off branch hanging over a depression in the ground, and an illustration depicts it that way, but in the earliest versions of the story, it’s actually said to have been a “large forked branch” with no indication of the branch having been cut. This shows the way the story has changed through the years. Likewise, most versions say the depression was twelve or fifteen feet, but earliest versions state that it was only seven. Obviously the pulley was seen as a sign that something had been lowered into the ground at that spot, and considering rumors of pirate activity, the three boys got to digging into the clay earth, and it’s said that they even saw the old marks of pickaxes as they dug. At ten feet deep, they struck a platform of aged oak logs; at twenty, they struck a second such platform; and at thirty, a third. They gave up when the ground became too difficult for them to dig with hand tools. Now already, this story contains some red flags. The detail of the pulley seems designed to indicate that a treasure was buried there, but surely if someone were trying to hide a treasure, they wouldn’t leave behind the pulley they used to lower it to mark the spot. Additionally, the detail that they could still see the marks of the original diggers’ pickaxes after the hole had been filled in for perhaps a hundred years must be further embellishment, an image meant to convince an audience that treasure was down there. But we don’t really need to weigh the believability of the tale, because its lack of historical documentation makes it dubious from the outset. There is no record of this event occurring until the first accounts of the story in 1860s newspapers. Historians have attempted to verify the details, and all they’ve been able to confirm just further discredits the tale. A couple of the characters, Daniel McInnis and Anthony Vaughn, did exist, but they were not kids. They were in their thirties. Also, the island was not uninhabited. In fact, McInnis and Vaughn owned property there. And though, according to the legend, these original treasure hunters would also be involved in the next few excavations, having convinced others of what they’d found, it is telling that neither the ship’s pulley nor any part of the oak platforms was preserved as evidence. Already we see that, while elements of it may be accurate, key parts of the transmitted legend are demonstrably false, and this does not bode well for the overall reliability of the tale.

Next came the early 19th century dig, funded by one Simeon Lynds, a wealthy Nova Scotia local who was intrigued by the claims of McInnis and Vaughn, gathered investors, and formed the Onslow Treasure Company. Accounts place this dig in 1803, or was it ’04, or perhaps ’02, ’01? It’s all rather vague, since again, there is no primary source attesting to this event until 60 years later, which is rather surprising since surely such a company, with investors, would have left some kind of paper trail or might have been mentioned in area newspapers at the time of its formation. According to the legend, which again, did not appear for several decades, this company’s efforts supposedly also resulted in some further tantalizing evidence that a treasure was buried below. They continued to find oak platforms every ten feet, and since the claim is that they penetrated all the way to about 98 feet, this means they encountered some seven platforms of oak logs, none of which were ever kept for study and proof. Just imagine, too, if this were true, what kind of an engineering feat is being attributed to pirates or whoever supposedly left these platforms behind. They are said to have dug directly downward more than a hundred feet with, we must assume, only rudimentary tools, and used a single tackle block on a tree branch to lower not just whatever chests are said to be down there, but also each and every oak log used in the platforms. It seems like a lot of strain on that poor pulley. The Onslow Company is said to have further discovered ship’s putty, which sure must have been hard to discern among all that clay earth, as well as charcoal and coconut fiber, this last discovery seeming especially important, since coconut was not native to Oak Island. But yet again, this purported evidence was not preserved except orally, in the legend that would eventually be put down in writing as if it were historical fact.

Especially tantalizing was the reported discovery by the Onslow Company of an inscribed stone tablet at 90 feet. The earliest reports only indicate that a stone with “marks” was found at that depth, but this element of the story has taken on a remarkable life of its own. The legend has it that, just beneath this stone, the Onslow Company diggers drove an iron bar five feet deeper before quitting for the day and felt it strike something wooden. For some reason, rather than assuming it was yet another platform, which he should have come to expect at about that depth, he believed he’d found a treasure chest that he would be able to dig up the very next morning. Why he wouldn’t have just dug it up right then is another unbelievable part of the story. Instead, they all left, and when they returned, the hole was flooded to around the 40-foot level. No amount of bailing managed to lower the water level, so they tried to angle in downward from a second tunnel to the side, hoping to avoid whatever spring they’d opened, but this one too flooded, causing them to eventually call it quits. This flooding of the tunnel, which even sixty years later, in the first known written accounts of the incident, is portrayed as natural, would eventually become a major part of the legend, that the pit had been booby-trapped with “flood tunnels.” More on that later. What’s interesting here is that, after this supposed discovery of chests at 98 feet that the company was prevented from recovering by the flooding, the legend tells us that the stone with strange markings was deciphered, and that its message stated, “10 feet down, two million pounds.” Once again, like the pulley and the platforms and the coconut fiber, seemingly incontrovertible evidence of there being something down that shaft is cited, and once again, there is no proof that it ever existed.

The diagram of the Money Pit as it appeared in the Rotary magazine.

The translator of the marks is cited variously as a “wise man,” or a “professor,” or a “cryptologist,” but is never identified. One may find illustrations of the stone and its markings in books now, but this drawing did not appear until 1949, which is especially strange since by that time, there had been a variety of other publications about the Oak Island legend, including a detailed “prospectus” produced by one later treasure hunting syndicate and a 1936 article in Popular Science, all of which surely would have reproduced such an image. According to the few mentions of the stone in correspondence and in earlier versions of the legend, it was said to have passed between various people, being used as the back plate in a fireplace at one point, and being used as a hammering table by a Halifax book binder until any inscription was conveniently destroyed. Despite rumors that it was in the possession of a local historical society, there is some sense that it disappeared after 1912, if it ever even existed. The drawing just kind of manifested in 1949 in the book True Tales of Buried Treasure by Edward Rowe Snow, a historian of New England whose work can be honestly said to have some reliability issues. The drawing he put in his book appears to have been provided to Snow by a local reverend named Kempton who was writing about the legend himself and had been in correspondence with the current group of treasure diggers then searching the pit, who interestingly believed Kempton’s ideas about the Money Pit were inaccurate. Kempton claimed, in letters, to have received all his materials from an unnamed “minister,” who actually wrote his manuscript and “did not give…any proofs of his statements.” Whether or not Kempton actually drew the stone’s symbols himself, as some believe, or actually did receive them from some third party, they are quite clearly a fraud, undermining many theories about the Oak Island pit that rely on examination of its symbols, as will be further discussed in time.

The last of the treasure digs on Oak Island said to have involved one of the original three treasure finders, Anthony Vaughn, and organized as a treasure company with investors again by the enigmatic wealthy local Simeon Lynds, was called the Truro Syndicate and appears to have formed around 1848 or 1849. This was the group that is said to have dug an entirely new shaft and used a horse-driven auger, which they claimed bit into both wood and metal, that encountered what they described as loose metals like coinage, and that pulled up a piece of gold chain. Interestingly, we do have some documentation of this dig previous to the 1860s newspaper accounts, in the form of an 1849 document granting permission for the syndicate to dig at the location. If we examine the claims made about this effort, we again see indications of embellishment. The first are the claims of what their auger encountered. It should be noted that they did not find treasure at 100 feet, as the phantom inscribed stone and the previous effort’s supposed findings would lead us to believe, and subsequently, later translations of the “inscribed stone” suggest it actually told of treasure to be found “40 feet down,” indicating they just had to dig a bit farther, down to 130 feet. It was during these deeper diggings with an auger that a few links of gold chain were turned up, which certainly sounds impressive, until you read the earliest accounts and find that these links were “possibly from an epaulette.” That means we’re talking about three tiny links of a kind of chain that may have come off the clothing of any number of visitors to the treasure dig during the last fifty years. Likewise, in these later digs, any time wood is encountered, it must be remembered that, even according to the legend itself, the Money Pit had been the site of multiple dig operations that were later abandoned, and thus may have been full of the refuse from previous treasure-digging attempts. This 1849 syndicate’s claims that, in addition to punching through an empty space, they drilled through wood and metal, including “loose metals” they took to be coins, can also be logically explained by the debris from the previous digs, judging only by the later stories told about them. Remember that they had supposedly dug cross-tunnels in an effort to bypass the flooding, which would account for any voids the Truro syndicate’s shaft may have encountered. Additionally, there are reports that the platform and apparatus of at least one previous dig had collapsed and fallen into the pit, which accounts for further wood and metal that the Truro auger may have struck, including some “loose metals,” like chains.

The baseless illustration of the 90-foot stone that surfaced in the 20th century.

It is not entirely clear how the operators of the Truro auger determined that they were actually drilling through these materials, though, especially the “loose metals” they took to be coins. According to the legend, they simply knew because of the sounds they heard and how easily their drill turned. The bit of gold chain it’s claimed they brought up was in mud, but if this bit of gold was encased in mud, then it was not in a chest, or if the auger was able to pull gold chain up its length, and the mud aggregated along the way, then why were no loose coins ever likewise pulled up? The simple answer is that they misconstrued the sound. One 1861 letter written by a visitor to a later treasure dig at the site indicates that the soil being brought up by the operation then underway was mostly “composed of sand and boulder rocks,” indicating that the drill in 1849 may have encountered gravel. The sound of such loose stones being turned would certainly have struck the ear as sounding like coins, especially if that’s what they wanted to hear. And interestingly, the very fact that gravel was encountered deep within the Money Pit helps to explain the flooding in the hole and to dispel the notion that the flooding was due to booby-trapping. Typically, the flooding is said to be unnatural because the earth was clay, and thus impermeable, but the aforementioned 1861 letter from Henry Poole, Esq., the visitor to the later diggings, states clearly that “[t]he watercourse, by which the original money-pit was flooded, is in all probability a layer of gravel creation,” gravel being extremely permeable. Really interestingly, the earliest mention a flood tunnel booby trap theory appears in one of those later news articles, this one from 1861 and called “The Oak Island Folly,” which was actually ridiculing people who wasted their money chasing after a treasure on the island. In it, the author states that “the theory on which these deluded people are proceeding [is that] the money had been buried and sluices or communications with the sea, so constructed, that the localities of the treasure was flooded, while the vicinity was comparatively dry." It is unclear what “vicinity” is being referred to as dry, but here in 1861 we see the theory had already taken hold.

Some of the claims of what the Truro syndicate found appear to have originated from an anonymous 1861 letter, written by one “Patrick, the digger,” who claimed to have been part of the Truro dig and was responding to the derision of the recent article. Much of what this Patrick states is just repeating what the news article had said about the claims of treasure diggers, though when he mentions their boring through loose metals, he actually says, “coins, if you will,” making explicit the claims that they had drilled through a treasure chest. And what happened to those chests at around 100 feet? Well, according to Patrick, the digger, they dug four separate shafts, on each compass point surrounding the original pit, and they dug deeper than the original pit’s depth, and dug directly beneath it, encountering no water at all. He says that what happened then was the treasure chests previously bored through, along with the water from the flood tunnel, crashed through into their new tunnel, filling it with water and soil. There are a few conclusions we can draw from this letter. One, if it were true, then the treasure was there, at around a hundred feet, not down a hundred feet farther, near bedrock, as some later treasure hunters who dug deeper and deeper have insisted, and it would have still been present in the bottom of the shafts among a slurry of water and mud after supposedly crashing through. We can eliminate this possibility because not a damn coin of it was every turned up by the many future treasure diggers who excavated and bored those same old shafts through the years. Two, it if were true that several other shafts were sunk on all sides of the original Money Pit, to an even greater depth and beneath it, encountering no water, then it would seem to disprove the claim of a flood tunnel booby trap. However, it would also seem to disprove the notion that a layer of permeable gravel was present to allow water into the shafts. But we know that water has filled the pit, so we are left with a third and more convincing conclusion, that the anonymous Patrick, the digger, is not a reliable source.

Diagram of geologist who observed manmade structures at Smith’s Cove, including speculation about its purpose.

It must be remembered that all of these details about these digs, not only the original find by McInnis and the others, but also the Onslow Company effort and the Truro syndicate operation, come to us through later newspaper accounts and dubious reports like those of the anonymous Patrick, the digger. Thus we might look askance also at the further claim that the Truro syndicate discovered further evidence of the flood tunnel in the form of drains on a nearby beach at Smith’s Cove. According to the legend, one of the original pit finders, Anthony Vaughn, upon learning that the pit was filling with salt water, not fresh water, led the group there, having recalled seeing water “gushing down the beach there at low tide.” Investigating, they found that the beach was “artificial,” with tons of coconut fibers beneath the sand—which, recall, is not native to the island—and five box drains or finger drains, constructed with beach rocks. We know that these manmade structures actually existed, though, because geologists, both in the 1960s and the 1990s, confirmed the existence of both the coconut fiber beneath the beach and the drains. However, the findings of these geologists did not support the notion of a flood tunnel booby trap. Geologist Robert Dunfield, in 1965, determined that the Winsdor limestone layer, which is honeycombed with natural watercourses, intersects with the Money Pit, making the flooding an entirely natural phenomenon. Reports that the waters flooding the pit rose and fell with the tide were thought to indicate that it was coming from the beach through a tunnel, but its water level only moved around a foot and a half, compared to the nine-foot difference between high and low tide at the beach. If the legend were true, and one could see all the water gushing out of the flood tunnel through the drains as the tide ebbed, then it would seem a simple thing to just wait for it to drain out, stopper the box drains, and dig away. But the fact is that it was flooding by a natural watercourse, not a tunnel connected directly to the beach. And simple logic tells us that no such flood tunnel could possibly have worked, not just because the engineering feet of cutting a drain some 600 feet from the beach to a treasure chamber would have been impossible, but also because no evidence of a constructed flood tunnel has ever been found. Such a tunnel would need to be lined, with flat stones, for example, or cement, and would have been observable. Treasure hunters on Oak Island would have people believe that these tunnels were cut into bare earth, perhaps filled with beach rocks but not lined. Such a tunnel, inundated by seawater daily for hundreds of years, would collapse, fill with silt, become clogged by mud. They simply would not work.

Despite the fact that the flood tunnel theory is manifestly impossible, the presence of manmade structures at Smith’s Cove and of what does appear to be an artificial beach have long puzzled those seeking to explain them. Indeed, for a long time, Smith’s Cove seemed the only genuine mystery of Oak Island. Now, though, that mystery has been credibly solved. Flood tunnel theorists claim coconut fibers were laid out beneath sand to act as a sponge and direct water into the box drains. Since coconut fibers were long used as shipping material, to pack cargo and prevent its movement, this notion went well with ideas about pirates or other early mariners having constructed the tunnels. Other notions have suggested that the island was used by smugglers and their packing materials were simply discarded on the beach, or that it came from shipwrecks in the distant past and was deposited there by storm activity, though these ideas did not explain the drains. Among the first theories to explain everything was that it was a kind of filtration setup to draw seawater toward a nearby well, turning it to fresh water. However, this was proven false by the existence of freshwater wells elsewhere on the island. Finally, in 2010, researcher Dennis J. King proposed the most convincing explanation: that it was the remains of an ancient salt cooking operation. In my recent Blind Spot patron exclusive minisode, I discussed the early activity of European fishermen around the Atlantic coast of Canada. Some of these fishermen, specifically French and English fishermen, were known to land on the Canadian coast to preserve their fish before their return voyage by drying and salting them. And the very first owners of Oak Island in the 1700s were known to use it as a base of fishing operations. Back then, salt was not so very plentiful as it is today, and it was heavily taxed. In fact, a French salt tax is credited as one of the causes of the 1789 French Revolution. The solution for Atlantic fishermen was to cook their own salt, and indeed the structures at Smith’s Cove bear some similarity to salt works in Japan and Normandy. This explanation actually accounts for both the drains and the artificial beach, as the seawater, controlled by a dyke, is filtered through the sand and coconut fiber, the sand catching some salt and the coconut fiber removing sand and silt, whereupon the saltwater solution was carried through the drains to a hypothetical nearby well. Salt could theoretically be harvested and boiled from the seawater in the well, as well as from the sand, a more laborious process. While this explanation too is theoretical, it’s a theory that accords with history and with geology. It’s simply a far more trustworthy conclusion.

So there we are. The legend, nearly fully formed already, with its claims about markers and booby traps, came to wider attention in the newspaper articles of the 1860s. Even though some of those earliest reports called the treasure hunts there foolish, further treasure hunting operations followed, as did further claims of evidence for the existence of some buried treasure there. The story then passed into folklore in the 20th century, when it was included in books like Edward Rowe Snow’s True Tales of Buried Treasure, and this process would continue with The Rotarian and Reader’s Digest articles, and would spread further in numerous anthologies that collected stories of supposed unsolved mysteries, books that were very popular for a long time. The process of legend-making would reach its apogee with the spread of the story on the Internet and the absolutely pointless History Channel program. As I have shown, nearly every major claim related to the Oak Island Money Pit has been reasonably and believably refuted. And yet, we haven’t even really scratched the surface of this legend. We’ve only looked at the earliest of its stories, the tales told about digs that occurred before any known documentation. What about later findings? What about the claims of treasure hunters since? What about further evidence and artifacts said to have been found there? What about the videos that are said to prove there are treasure chambers and skeletons down in those depths? What about all the claims of landmarks and conspiracies promoted on the History Channel? And most importantly, what about the why? If this were all a hoax from the beginning, what was the purpose? All of these further mysteries I will explore, like side shafts branching from the main bore hole, as this series goes on.

Further Reading

Bowdoin, H. L. “Solving the Mystery of Oak Island.” Colliers, vol. 47, no. 22, 19 Aug. 1911, pp. 19-20.

Joltes, Richard. “History, Hoax, and Hype: The Oak Island Legend.” Critical Enquiry, 2006, www.criticalenquiry.org/oakisland/index.shtml.

MacDonald, David. “Oak Island’s Mysterious ‘Money Pit.’” Reader’s Digest, January 1965, pp. 136-40. Oak Island Scrapbook, www.oakislandbook.com/wp-content/uploads/Readers-Digest-January-1965-OakIslandsMysteriousMoneyPit.pdf.