Omens, Charms, and Rituals: A History of Superstition

On many porches right now there rot pumpkins that were hollowed out for Halloween and transformed into lanterns with candles or electric lights, illuminating grimacing grins from within. Long is the history of this ritual, though it was not always pumpkins that were carved, but rather turnips and other vegetables, their glowing visages said to ward off the spirits that walked the earth that day. They are called Jack-o-lanterns, however, because of a Western European folktale about a particular spirit said to walk the earth. The story of Jack of the Lantern, or Stingy Jack in the Irish version, is the story of a wicked man who tricked the Devil. The specifics of the tale vary from region to region, but essentially, this man Jack, either a blacksmith or a common thief, convinced the Devil to transform himself into a coin, which Jack put into his pocket next to a cross, or that he lured the Devil into a tree and carved a cross onto its trunk, or by some tellings he did both, trapping the Devil more than once. The thrust of the story is that Jack promised to free the Devil if the Devil promised not to take his soul. When Jack eventually died, he was too wicked to go to heaven, but the Devil, because of their bargain, could not take him. Thus, he was doomed to forever wander the darkness. The Devil gave him a burning coal to light his way, which some say he placed into a hollowed out turnip. In fact, the legend of Jack o’ Lantern is merely one iteration of an older folktale, in which the man’s name is given as Will rather than Jack, and he is doomed to wander with a bundle of sticks used as a torch, called a “wisp.” You may have heard of the Will-o’-the-Wisp: they are reportedly magical lights seen in the night, said to lure travelers to their doom. They have been called many things through the ages, including fairy fire and fairy lights, hinkypunk, and Irrlicht, or deceiving light, in German, which was later Latinized as ignis fatuus, or foolish fire. The reason for these latter names is clear. The lights were most commonly seen in marshland and swamp, and if a traveler followed them, they became lost, thus making them portents of ill fortune and death. They were first written about early in the 14th century, in a Welsh work that gave another interesting name for the phenomenon: the corpse candle. This indicates that the lights were often seen floating around graveyards as well, which corresponds to the claims of modern ghost hunters who have reported sightings of ghost lights or orbs in cemeteries. As it turns out, there are some rather compelling scientific explanations for this phenomenon. Due to the decay that occurs both in marshes and graveyards, the presence of methane gas likely results in a chemical luminescence, or chemiluminescence. This is, essentially, the much maligned “swamp gas” explanation of UFO sightings, but it remains the most likely rational explanation of will-o’-the-wisp, fitting the features of reports better than other explanations, like bioluminescent insects, St. Elmo’s Fire, or ball lightning. While science provides a rational explanation today, though, it must be recognized that folklore did the same job in ages past, providing a rationalization of an otherwise unexplained phenomenon. And the fact that it was thought to be a harbinger of bad luck too makes sense, for certainly there must have been travelers who wandered into a swamp following the lights they saw there and got stuck, or lost their wagons and carts or even their lives. They saw the lights, and afterward, they met ill fortune or death. But of course, the real cause of it was leaving the road and forging into marshlands, not the luminescent phenomenon in the distance. Such is the nature of superstition. It attributes a false cause to both good and bad fortune, giving believers some agency in it, through ritual, as well as some sense that they understand a world that is full of mystery and misfortune.

To connect this topic to the recent series, the myth of vampires was, from its origin, a superstition. The word derives from a Latin word which means “to stand over in awe,” and it’s typically defined as an irrational belief borne out of ignorance and fear, but as I stated, many superstitions can be seen to have derived from fallacious reasoning, specifically the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy, which means “after this; therefore, because of this” and describes the flawed logic of ascribing a cause to some phenomenon simply because the phenomenon occurred after it—your basic confusion of correlation or coincidence with causation. In the vampire superstition, we see villagers assuming that some rampant disease that occurred after a certain person’s death must be caused by that dead person. Thus, it seems, superstition can beget folklore, or vice versa. As a further example of the folklore of vampirism being related to superstition, we see the element of vampire lore that revenants have no reflection in a mirror, which, even if Bram Stoker was first to connect it to vampires, still reflects, if you will, the superstition that mirrors captured and showed the human soul, which Count Dracula did not have. Of course, we can see this explanation of reflection as an attempt to rationally explain, in the absence of a true understanding of the process, why one could see oneself in a looking glass. That wasn’t you in the glass; it was an embodiment of your eternal self. Thus we can easily understand the superstitious belief that breaking a mirror, or even looking at one’s reflection in a cracked mirror, can result in bad luck. In fact, it was sometimes believed to portend death. The very specific number of seven years’ bad luck may have evolved from an old Roman belief that the body and therefore the soul renewed itself in seven year cycles, a superstition that remains popular today, with many believing the erroneous myth that the human body undergoes a kind of cellular regeneration every seven years. This belief about mirrors was once so pronounced that if one broke a mirror, it was considered imperative to grind up its pieces in order to free the soul trapped within. The notion that mirrors separated the soul from the body in this way led many to believe that they made our souls vulnerable to being taken by the Devil or by other spirits. This appears to be the origin of the superstitious practice of covering mirrors after someone has died. If one wasn’t afraid of the ghost of the departed spiriting away one’s soul from the mirror, then one was typically afraid of looking into the mirror and seeing the reflection of the ghost behind them. Thus, mirrors have also long been used as a kind of spirit trap, placing mirrors in doorways to catch any ghosts that might step into them, thinking they were walking into another room.

Accusing the anointers in the great plague of Milan in 1630. This image comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom. Refer to Wellcome blog post (archive). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

As we see in vampire lore, disease breeds superstition, and nothing is so likely to generate such beliefs as an epidemic disease, like the Plague. The superstitious ritual of blessing someone who sneezes is sometimes claimed to have originated with the Plague, but this is not accurate. Medieval texts as far back as the 13th century describe people responding to a sneeze with the phrase “God helpe you” as a blessing against pestilence. It is true, however, that the Black Plague originated numerous false cause claims as the blighted communities sought to blame the disease on something or someone. These false cause superstitions typically resulted in scapegoating, which we have seen in the libels and persecutions against Jews, when they were said to have poisoned wells. I spoke about this in my episode In the Footsteps of the Wandering Jew. Churchmen also blamed the plague on sin, and on witchcraft. Indeed, in Italy, there was even a name for the scapegoats of the plague, whether Jewish or not. They were called “anointers,” and they were thought to spread the disease through poisonous oils that they sprinkled from vials. This led to many innocent people being hunted by mobs simply because someone, likely a personal enemy or rival, accused them of being an anointer. As an example, in one incident, an 80-year-old man seen brushing off a bench in church before sitting on it was said to be anointing the benches with poison and was set upon by an angry mob and dragged through the street, likely to his death. Other superstitions borne from casting about for a cause of the plague resulted more from ignorance about the nature of disease rather than from scapegoating. As I have discussed before, the miasma theory of disease reigned prior to our modern understanding of germ theory, and it was thought that vapors or emanations spread disease, providing a very basic understanding of airborne disease. The bubonic plague was not airborne, however. It was caused by the bite of infected fleas or by being exposed, through broken skin, to infected material. Nevertheless, as it was noticed that those near other infected or who were around the plague dead frequently became infected themselves, it was thought that they must be contracting the disease by inhaling the infectious vapors, those bad smells, which they reasoned could be countered by good smells, or even just different smells. Thus the line, “pocketful of posies,” is immortalized in the nursery rhyme Ring around the Rosie, inspired by the Black Death, as flowers were kept on one’s person to stave off the smell that slays. This miasma theory of disease also resulted in the superstition that one should hold one’s breath while passing a graveyard. Less logical were other supposed charms against the bubonic plague, such as wearing a toad around the neck or rubbing pigeons on one’s buboes. Nor were all flowers alike considered effective against the plague. Indeed, hawthorn blossoms were thought to actually bring the plague, since they apparently smelled of the plague dead. This has since been explained by science as the presence of Trimethylamine, a compound present in hawthorn as well as in decaying flesh.

Hawthorn trees and shrubs seem to have become connected to numerous superstitions, perhaps because of the smell of death surrounding them. In Vampire lore, it was often stakes of hawthorn, or hawthorn cuttings with thorns, that were used to “kill” vampires or to keep them away. So while they seemed bad luck as they related to the Plague, they were good luck when it came to dealing with revenants, and this mixed significance, as we will see, is rather common. Romans believed hawthorn sacred and used it for torches, or tied their leaves to cradles to ward off evil. Pliny the Elder wrote that destroying a hawthorn bush would get you struck by lightning. Yet when the Christian Church spread, it was claimed that the thorns placed on Christ’s brow were of hawthorn, giving it a negative connotation that was amplified when it was later claimed that witches commonly used the plant in their spell-making. Likewise, the belief that walking under a ladder is bad luck comes from the fact that a ladder, leaning against a building, forms a triangle. Triangles were symbolic of life to Egyptians, and of the Trinity to Christians, so pagan or not, passing through such a sacred symbol was considered blasphemous. Or at least, that’s one explanation. There is also the simpler explanation that ladders were used in medieval gallows, and one just wouldn’t want to pass under those, or the even simpler explanation that you wouldn’t want to pass under a ladder because objects or people were apt to fall on you. The true origins of bad luck superstitions are often hard to pinpoint like this. Was it bad luck to pass someone on a staircase because it was believed ghosts haunted staircases, or because one was more likely to have a bad fall if they ran into someone there? Was it bad luck to let milk boil over because it was believed to harm the cow and make it more likely to stop producing milk, or because milk was precious and only kept in small quantities, fresh, in an age before refrigeration? Is the number 13 considered so unlucky (such that it causes a fear complex known as Triskaidekaphobia) because in ancient astrology it was thought that during the 13th millennium chaos would reign? Or because in Norse mythology, Loki attended a feast of the gods as the thirteenth guest and initiated Ragnarök—the destruction of the gods—with a deadly prank? Or rather, is it because, at the last supper, the betrayer, Judas Iscariot, was the thirteenth person at the table? We may never know, but we do know that, to Jews, it is an auspicious number, the age at which a boy becomes a man, a number representing the word for love. Then again, it has also been suggested that fear of the number 13 actually derives from an anti-Semitic fear of the Jews.

a mummified hand of a hanged man, used for folk healing as well as folk magic. Image credit: www.badobadop.co.uk. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Many superstitions go further than just a fear of bad luck when, like the witnessing of the will-o’-the-wisp, objects or events are considered to be omens of imminent death. Much like one’s image in a mirror came to represent their soul or their self, and the destruction of that mirror was considered an ill portent, portraits too were thought to represent a person’s well-being or true self, and if they fell from the wall, it was thought an omen of death. Perhaps this notion is what inspired Oscar Wilde’s wonderfully creepy short story, “The Portrait of Dorian Gray”—if one could safekeep their portrait for an eternity, perhaps it might render them immortal, and might the portrait itself change along with the quality of its owner’s soul? Likewise, as clocks became were used by more and more people, and as we began to measure our lives in minutes and hours rather than by the progress of the sun in the sky, by the 19th century, a stopped clock had come to represent the ceasing of life. Thus it is no great stretch to understand why a stopped clock that may suddenly and unexplainably chime could be seen as an omen of death. Many were the unsupported claims that a broken clock would inexplicably ring out just before an ill loved one’s passing. This may have been related to superstitions about not talking during the chiming of bells, since that sound had been associated with death all the way back to the Plague, when churches rang their bells to mark a death and were ringing almost constantly. Many such superstitions arose from those who dealt with death and attempted to understand the process by which death spreads, as we saw with the lore of revenants. The souls of the dead were thought to remain a while and to pose some mortal or spiritual threat to the living in other ways besides rising from the grave a vampire, as we saw with beliefs about mirrors. This idea explains why it was considered bad luck to encounter a funeral procession and not take off one’s hat or join the procession for the rest of its march, and it was thought that pointing at such a procession would mean certain death within a month’s time. Likewise, a superstitious individual would not walk over anyone’s grave nor remove flowers from a resting place, and if they felt a chill, they thought someone had walked over their grave—even if they had not yet chosen their burial place. Not all superstitions about the dead involved ill fortune, though. For example, it was thought that touching a dead person at their viewing could impart good luck, could heal certain illnesses or conditions like warts, which they believed were passed to the deceased, or would at least prevent the dead from haunting you. More specifically, it was believed that being stroked by a dead criminal’s hand could cure facial cysts and goiters. It was not so much their criminality but rather their untimely death at the gallows, for if you recall, there was a belief about people having an appointed 70 years of life. Thus, one who dies before their time, while one folk belief said they may rise as revenants, another had it that the additional life denied them acted as some kind of mystical palliative. As murder victims and suicides were not frequently stumbled upon, it was criminals, who were publicly hanged, that became the source of this strange medicine, and it was not uncommon so see people approach the freshly hanged to touch their hands, or for mothers to pass their afflicted infants to the executioner so that he would press the hands of the dead on their faces. The belief was so prevalent that doctors were known to keep withered hands in their kits to rub on their patients.

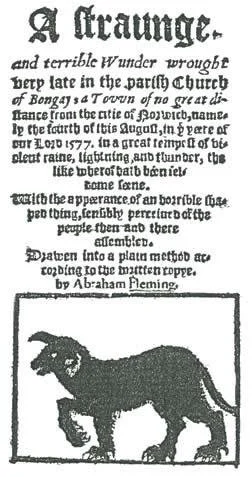

There are numerous superstitions about animals having premonitions about death as well, for example, dogs, which were invested with prophetic abilities in both the Egyptian and Roman cultures. Perhaps because of this ancient folklore, the howling of dogs became an omen of death in various European cultures. However, some may have had other reasons to be struck with terror at the sound of a howl in the night. If I were speaking of France, you might assume that I refer to the howling of wolves as striking terror into the hearts of those who hear it, but hearing howling at night was also a cause of great fear throughout the UK long after wolves were stamped out in the 14th century. You may suspect that I’m going to bring up werewolves now, but instead, I speak of the beasts on the moor, or folktales about fearsome black dogs. Many are the tales of these supposedly supernatural creatures: the Cú-sith of Scotland, the Gwyllgi of Wales, and the Gytrash of Northern England. But perhaps the most famous is the Black Shuck which is thought to range through countryside of East Anglia. Like werewolves, and like the will-o’-the-wisp, it was thought to haunt dark roads at night and prey upon travelers, recognizable by his blazing eye, which, of course, sounds like it could be mistaken for a will-o’-the-wisp. It was claimed that its terrifying howl could be heard, but not its footsteps as it galloped to set upon you, which of course causes one to doubt that anything was actually running toward those who claimed to have had close encounters with it. If one was not killed by the Black Shuck, it was still considered bad luck to encounter them, and travelers were advised to close their eyes if they heard the beast’s howling, even if it might just be the wind, a specification that certainly suggests many such supposed close calls were only encounters with the howling wind. One encounter describes a more corporeal beast, however. In Suffolk, in 1577, it is recorded that a black dog burst into Holy Trinity Church, leaving scorch marks on the door that today are called the “devil’s fingerprints,” and then killed two churchgoers where they knelt. Accounts like this one, and superstition surrounding the Black Shuck and other black dogs like it would go on to inspire the Sherlock Holmes story, The Hound of the Baskervilles. If I were to act the Sherlock here, I’d point out that archaeologists have examined the teardrop shaped scorch marks and determined they were apparently purposely made with candle flames, and descriptions of the Black Shuck entering the church with the sound of a thunderclap, in conjunction with the fact that a violent thunderstorm occurred on the same night, leads one to believe that the imaginations of those present may have run away with them.

Account of the appearance of the ghostly black dog "Black Shuck" at the church in Suffolk in 1577.

Superstitions about black dogs now lead me back to the trailhead by which I embarked on this investigation, recommended to me by generous patron Jonathon: black cats. Jonathon suggested I devote an entire episode to black cat superstition, and I hope he’s not disappointed that instead it serves as just part of a longer episode about superstition generally. As we saw with other categories of superstition, whether something represents good or bad luck is not always clear and varies from culture to culture. The same is true of cats, and black cats specifically. As with dogs, cats have been domesticated since great antiquity, giving us plenty of time to develop folklore and superstitious beliefs about them. In various global traditions, they long served as symbols for protection, independence, and good fortune. Going all the way back to Egyptian and Norse mythology, cats are considered sacred, servants of the gods, vanquishers of evil spirits. Their positive reputation as protectors of the household grew with their role as mousers over the centuries. And while it is commonly thought in America and many other places that a black cat crossing one’s path is bad luck, in Great Britain, Scotland, and Ireland, exactly the opposite is true. Owning or even seeing a black cat is thought to be a sign of coming prosperity. Indeed, so strong is the belief that a black cat brings good luck there that it is thought their deaths can bring an end to good fortune. Charles I, the Stuart king, apparently believed as much and set his guards to protect his black cat as if they were protecting his very life, which he believed to be so. As legend has it, his cat died regardless, and the very next day, while he mourned the loss of his beloved pet and his good luck, Cromwell’s men showed up to arrest him, leading to his eventual execution. This story certainly smacks of embellishment, but it illustrates the extent of the belief that black cats are good luck. Another example is the presence of dried cats walled up in buildings as lucky charms. Not only in the UK but also in other European cities and even in the buildings of colonial America, cats that were desiccated through smoking and then placed within the walls of buildings and posed as though in the act of catching a mouse, have been discovered. It’s thought that they were placed there as a kind of scarecrow, to drive off potential ghosts or evil spirits, but in truth, we don’t know the purpose of the practice. One thing that modern science has shown us, though, is why the black cat’s coat is black, and it does indeed seem to indicate that the creatures are good luck. Their coats are black due to a certain mutant gene that also makes them more resistant to disease, and which scientists are studying for possible applications in medicine, specifically to treat HIV.

A depiction of Cathars worshipping a cat as if it were the Devil, and preparing to kiss its backside, an act called “osculum infame,” the kiss of shame. Image credit: cathar.info

Unsurprisingly, we have the Christian Church to thank for demonizing black cats. It seems to have begun with the odd belief that cats are somehow lewd. Well, certainly they do often present their anus to us with an upturned tail, but I rather think that such a belief says more about medieval Christians than it does about cats. I imagine they saw a cat’s exposed rear and then interpreted the cat’s backward glance as some kind of come hither look. Cut to them thumping their bibles and calling cats harlots. Eventually, it was thought that they were not just lewd creatures but also the very Devil in disguise. In the 12th-century tale of St. Bartholomew, the Devil takes the form of a cat. And in the Albigensian Crusade, a 13th-century military campaign against heretics in the south of France, it was claimed that the Cathar sect there did things like kiss the anus of the Devil, who had taken the form of a black cat. Indeed, it is suggested that this was the why they were called Cathars. From there it is no surprise that the same accusations were resurrected against accused witches by the Inquisition. Thus black cats were either the devil incarnate, or they were the familiars of witches. Some claim that the association of witchcraft with cats goes all the way back to Greek mythology, when a figure named Galinthias, servant of Hera, tried to interfere with Heracles’s birth and was punished by being transformed into a cat and cast into the underworld to serve Hecate, goddess of witchcraft. However, this is a stretch. Hecate was more of a goddess of magic, as without the Christian notion of a devil, the concept of witchcraft was not really the same in Greek myth. Also, some versions have it that Galinthias was transformed into a weasel, making this a tenuous basis for the origin of the witch and black cat relationship. Nevertheless, they were believed to be connected, and this is the very origin of persistent superstitions about them. If a black cat crosses your path, it is thought bad luck because it means the Devil has taken notice of you. And a cat is thought to have nine lives because it was thought that witches could take on the forms of their familiars, but could only do so nine times. It may even be related to the notion that cats steal your breath, though this has the pretty simple explanation that cats like to lie on sleeping persons for warmth and may have unwittingly been responsible for smothering some children. But of course, rather than come to terms with such an innocent tragedy, the superstitious want someone to blame, and so it is not a cat that smothered their child, but rather a witch or even the Devil himself.

The suspicion that someone has performed sorcery against someone else has created many a superstition. There is a long-held, widespread belief in a curse that can be placed on people called the Evil Eye. It is mentioned in many ancient texts around the world and is even acknowledged in the Bible and the Koran. Essentially, the Evil Eye is thought to be cast by those who are envious, so it is thought that young children and those who are fit and beautiful are the most at risk. Because of this, outsiders with miserable lives were often accused of casting the Evil Eye, just as they were also singled out as witches. Because the curse, which was blamed for a variety of illnesses, was thought to be cast with a hateful look, people with eye imperfections, like a squint or a lazy eye, were also accused of giving the Evil Eye, when of course they could not help how they looked at people. Belief in the Evil Eye curse brought about numerous other superstitions in the form of lucky charms. The most common were amulets with eyes on them, but another you have likely heard of is the horseshoe. The symbol of the horseshoe has evolved through the millennia, from something that wards off the Evil Eye to something that brings general good luck, and how it is used has also changed, from keeping the opening facing downward to keeping it facing up, but its origin as protection against sorcery is certain. Likewise, there are a variety of superstitions about brooms, such as not sweeping after dark or not taking brooms with you when you move into a new house, all of which originate from the supposed use of brooms by witches. Likewise, it was common practice in the 15th century to put a pinhole in eggshells because it was thought a witch might otherwise use the eggshells to cast a spell on whoever had eaten the egg. Parents avoided cutting their child’s hair or fingernails in the first year of their lives for fear witches might use the cuttings to cast spells against them. Some superstitions that had their origin in fears about witchcraft contradict each other. It was said that cutlery laid crosswise was a sign of witchcraft, and indeed an easy way to support witchcraft allegations against an enemy, and thus even long after witch persecutions it was considered unlucky to lay cutlery across each other. But while it was claimed that witches laid cutlery into the sign of a cross, it was also claimed that they could be made uncomfortable in a room by hiding open scissors somewhere, again because it made the sign of the cross. But problems of logical consistency aside, belief in witchcraft led to belief in numerous apotropaic superstitions like this, such as the hanging of hagstones, or river stones with natural holes in the middle of them that were thought to have been made of hardened snake saliva and were believed to be effective charms against witches, or like the carving hexafoils, designs like pentagrams and daisy wheels that appeared to have an infinite pattern, into the walls of buildings as protection against witches, who were thought to get lost in following the patterns.

As I have looked further into superstitions for this episode, I have happily come to find that they are perhaps one of the more perfect expressions of historical blindness in the sense that the reasons for these traditions are murky. Often, they are the result of ignorance, but also of syncretism, the synthesis of different beliefs that happens when cultures clash. Ancient pagan beliefs are adopted and adapted by Christianity, obscuring their origins in a kind of revision of history. We have seen this again and again in my holiday specials about Christmas folklore and traditions. Another example is the superstition about things moving widdershins, or counter-clockwise. This originated in traditions that worshipped the sun and held sacrosanct its trajectory through the sky, but with the advent of Christianity, it became associated with witchcraft and the Devil. Likewise, the belief that spilling salt was bad luck originated with the simple fact that salt used to be a precious commodity, but Christianity transformed this into an act of the Devil, saying that salt must be sacred because it is used in making Holy Water. This then led to the notion that salt could be used to drive away evil, perhaps in combination with the odd idea that, like the infinite patterns of hexfoils, a pile of salt might confuse and waylay witches and demons who felt compelled to count them all. Thus we have the further superstitions of throwing salt over one’s left shoulder, where the Devil was thought to lurk, or protecting one’s home with applications of salt. What we see here is ancient tradition, twisted through syncretism until we have little sense of its purpose, and strengthened by ignorance, to forge a false cause belief that flies in the face of logic. Now, I may sound a little salty, and you may take my conclusions with a grain of salt, if you’ll excuse the puns, but I think all these examples, and many others, all of which I read about in my principal sources, Black Cats & Evil Eyes: A Book of Old-Fashioned Superstitions by Chloe Rhodes and Superstition: White Rabbits & Black Cats—The History of Common Folk Beliefs by Sally Coulthard, bear out this final evaluation. We live in a world of nonsense that has been handed down to us as wisdom and truth.

*

Until next time, remember, every time you tempt fate by boasting about your good fortune, and you knock on wood—or touch wood, as they say in other places—but you don’t know why, it all derives from Druidic belief in dryads, or benevolent tree sprites… or is it from the ancient Greek belief that touching an oak provided protection from Zeus? …or is it just from the 19th-century children’s game of Tig, from which we get the modern game tag, in which touching the wood of a tree made you safe? Jeez, I dunno what the point of researching this stuff is if I get three different answers.

Further Reading

Coulthard, Sally. Superstition: White Rabbits & Black Cats—The History of Common Folk Beliefs. Quadrille, 2019.

Davies, Owen, and Francesca Matteoni. “'A virtue beyond all medicine': The Hanged Man's Hand, Gallows Tradition and Healing in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-century England.” Social history of medicine : the journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine vol. 28,4 (2015): 686-705. doi:10.1093/shm/hkv044

“The Devil’s Fingerprints.” Atlas Obscura, 25 June 2020, www.atlasobscura.com/places/the-devils-fingerprints.

Edwards, Howell G. M. “Will-o’-the-Wisp: An Ancient Mystery with Extremophile Origins?” Philosophical Transactions: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 372, no. 2030, 2014, pp. 1–7. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24505048.

Merelli, Annalisa. “Hysteria Over Coronavirus in Italy Is Reminiscent of the Black Death,” QUARTZ, 24 Feb. 2020, qz.com/1807049/hysteria-over-coronavirus-in-italy-is-reminiscent-of-the-black-death.

Rhodes, Chloe. Black Cats & Evil Eyes: A Book of Old-Fashioned Superstitions, Michael O’Mara Books, 2015.