Firebrand in the Reichstag!

In this installment of Historical Blindness, we will delve into a topic that, although largely settled among respected historians, remains a living legend in the public mind, with most lay persons still believing long disproven lies to be true. This is a subject, it must be said, that still, some eighty years on, inspires passion and heated argument. As such, I feel I must make my intentions clear in a preemptive apology of sorts, offering assurances regarding my motives in undertaking to tell this story. In presenting the various narratives of this event, several of which have been propagated since it transpired, I do not intend to exonerate any one party, nor do I have any desire to present the Nazis, who feature prominently in the story, as anything other than the great villains of their era. Many before me have investigated this topic, and in making certain observations regarding culpability for this specific event, have been accused of trying to exonerate Hitler’s fascist regime and whitewash their crimes. Indeed, current day neo-nazis and white nationalists frequently tout some of the admirable historiography I will rely on here in their repugnant apologism of Nazi racism and their denial of the genocide that Hitler perpetrated. I must, therefore, make it absolutely clear at the outset that Hitler and his fascist National Socialist German Workers’ Party, aka the Nazis, can never be acquitted for the many monstrous crimes they committed against humanity and the ideals of freedom and equality. A search for truth among purposeful fabrications in the historical record may find that one specific crime traditionally laid at their feet may not have been perpetrated by them, but nevertheless, their reaction to said crime and the many subsequent offences committed by them, which cannot be denied, remain to damn Hitler and his Nazis forever.

But I get ahead of myself… To make a beginning, we must look further back, to the rise of Hitler and his Nazis, and to the volatile conditions of the Weimar Republic, crippled by the Great Depression and by insurmountable political division, which created a tinderbox awaiting a spark. This was the Weimar Republic in its death throes: a society gripped by an unemployment rate of almost 40%, a government that could not rule except by emergency decree and continual dissolution of a deadlocked legislature, and a very dangerous fascist newly installed as chancellor seeking to eliminate the political obstacle represented by the opposition Communist Party. The Nazi conflict with Berlin Communists had just culminated in the Communist Party headquarters, the Karl Liebknecht House, being raided, their firearm stockpiles seized, by the Berlin Police, the chief of which also happened to be a leader of the S.A., or Brownshirts, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. It was in this combustible atmosphere that, just after 9pm on February 27, 1933, the conflagration began.

The night was remarkably cold, 22 degrees Fahrenheit with an icy wind that blasted through the streets of Berlin, cutting through one’s overcoat to chill the bones. This wintry gale blew hard on the façade of the Reichstag, the grand edifice of German republicanism that had housed various legislative bodies and stood, with its ornate Neo-Baroque columns and impressive glass and steel cupola, for nearly forty years. The Reichstag was empty at this time of night: the last government official departed for the evening, the postman come and gone, the night watchman done with his rounds. Nevertheless, the streets around the Reichstag were not deserted completely; various passersby were still about, hurrying home through the cold or enjoying a bracing winter’s walk arm in arm with a spouse. One of these, a student come from the library and passing near the front of the Reichstag, heard breaking glass and, turning, saw a figure on a first-floor balcony with what appeared to be a flaming object in hand. The student immediately sought out a policeman who was walking his beat on the opposite side of the Reichstag; he pointed the officer in the direction of the figure he’d seen, slapping his back and insisting he investigate.

The Reichstag before the fire, from The Reichstag Fire by Fritz Tobias.

Upon reaching the spot the student had indicated, the officer, a sergeant, saw a broken window and observed a reddish glow within the building. Another passerby joined him to gawp silently, and then a third, a typesetter who had heard the glass breaking, thought he’d seen two men entering the building and tried to raise the alarm on the southern side of the Reichstag with a blind cry into the night that may not have even been heard. Having returned to find the sergeant and the other passerby, he joined them in staring at what was the restaurant on the first floor, seeing a figure inside passing before several windows, torch blazing in hand. They followed his progress. The sergeant drew his gun. The typesetter bellowed, “…why don’t you fire?” and the sergeant did, discharging his gun toward a window where the intruder could be seen and only succeeding in driving the firebug farther into the Reichstag’s interior. Only then did the police sergeant think to send passersby to raise the police and the fire brigade.

What ensued was a comedy of errors, with people running in all different directions: to a police precinct, shouting for help; to an engineering institute, pleading for the caretaker to telephone the fire brigade; and to the lodge of the doorkeeper of the Reichstag, demanding he activate the fire alarm. In response, the 32nd precinct scrambled a squad car but brought no reinforcements, the caretaker of the engineering institute fumbled with a phone book but failed to find the fire brigade’s number, and the Reichstag doorkeeper scoffed, refusing to believe the building was on fire until he went to see for himself. And when police finally tried to enter and do something about the matter, they found door after door barred. The doorkeeper, finally convinced of the emergency, was able to admit them by the north entrance, but they had to wait ineffectually for the House-Inspector to arrive with keys to the inner doors. The doorkeeper, in his panic, had not phoned the House-Inspector but rather the Chief Reichstag Messenger, who had activated the phone tree with the news. Luckily, the House-Inspector had heard fire engines while tucking into his supper, had called the doorkeeper himself, and was on his way, angry at not being called directly. Eventually, some 15 minutes after the arsonist’s entrance into the building, the police were able to gain entry as well.

The House-Inspector, a Lieutenant of the 32nd Precinct, and a few constables climbed the stairs, crossed the lobby and were met with the eerie sight of red light emanating from behind a monument to Kaiser Wilhelm. The curtains framing a door to the main Session Chamber were blazing, and through the glass door, more fire could be glimpsed. Upon entering the Session Chamber, they witnessed a sheet of fire rising behind the tribune and the Speaker’s Chair at the back of the chamber, as well as below, in the stenographer’s well. It looked to them like a brightly glowing church organ.

The House-Inspector also claimed to have seen numerous small, sputtering fires among the deputies’ benches on either side of the tribune. Firemen had meanwhile arrived, fighting a number of small fires in other lobbies, so the House-Inspector shut the doors and left with a constable to search out the arsonist. One of the firemen thereafter opened the door again and, struck by smoke and heat upon entering the Session Chamber and marking a great draft through the doors, thought it best to close the room off. But of course, the chamber was not truly shut off, for the great glass dome above had been breached by the fire, acting as a chimney and making of the chamber a furnace. Before long, the Reichstag’s Session Chamber would be absolutely cored out of the building.

The burnt-out Sessions Chamber, from The Reichstag Fire by Fritz Tobias.

The House-Inspector and the constable did not search long before, as they passed beneath a grand chandelier in the southern corridor of Bismarck Hall, a tall and bare-chested young man darted in front of them, coming from the direction of the rear of the Session Chamber. Upon seeing them, he froze a moment before trying to flee back from whence he had come. When the constable trained his pistol on the figure and called for him to raise his hands, the young man stopped and complied, heaving for breath. Searching his trousers, the constable found a passport with his name: Marinus van der Lubbe.

“Why did you do it?” the House-Inspector demanded, trembling in a fury.

“As a protest,” van der Lubbe said mildly, and the House-Inspector struck him.

Marinus van der Lubbe was taken away to endure an arduous interrogation, and by 11pm, the fire he had apparently set was extinguished, leaving only a charred black cavity at the heart of the Reichstag, where the Session Chamber had been. No one else was arrested on the scene, and indeed, no other suspects had been witnessed. Although the typesetter who witnessed someone breaking in thought at first he had seen two figures, it eventually seemed more likely to investigators that the second figure had been a reflection. And though there was subsequent report of a shadowy figure seen leaving the southern entrance of the Reichstag at about the same time as the window was being broken, receiving some sort of gestural signal from two women across the street and then fleeing, though not without a suspicious backward glance at the building, later this shadowy agent was determined to have been an innocent passerby taking shelter from the wind and then running off to catch a bus. And with Marinus van der Lubbe’s confession, which he gave gladly, in addition to his subsequent walkthrough of the Reichstag to show authorities how he had set the fire quite by himself, it appeared that the case was closed and the state had their man.

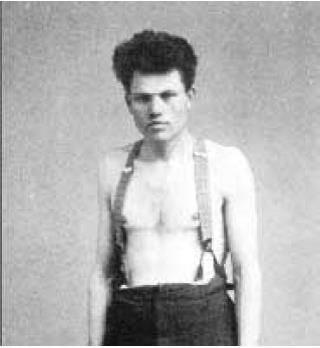

Marinus van der Lubbe, from The Reichstag Fire by Fritz Tobias.

But of course, if you have ever heard of the Reichstag Fire, you know it was not that simple. The event has become a pivotal moment in modern history, and in public perception, it has come to serve as a symbol for conspiracy and manipulation. It is looked at and referred to as the prototypical example of a “false flag” operation, or a covert operation executing some incident with the intention to deceive the world into believing said incident was perpetrated by some nation or group that in fact bears no responsibility for it. The Reichstag Fire has become the quintessential false flag operation, and has been used ever since in American political discourse to draw parallels and cast aspersions, fueling conspiracy theories from one extreme of the political spectrum to the other. After the attacks of September 11th, 2001, when the Bush administration declared a nebulous and unilateral War on Terror and whittled down civil rights with the Patriot Act, critics cried that 9/11 was his Reichstag Fire. When the tragic mass shootings of 2012 prompted an urgent national discussion of mental illness and gun violence, some conspiracy theorists callously suggested these events were staged by the Obama administration as part of a plan to declare martial law and disarm the populace, the idea being that they would be his Reichstag Fire, justifying the taking of our guns. Even leading up to the recent election of Donald Trump, some feared an imminent Reichstag Fire event that would allow Obama to extend his time in power or somehow rig the election against the Trumpites. And now, in the Age of Trump, fueled by genuine fearmongering from an administration that tells us any checks on its power, any obstruction of its agenda will result directly in terror attacks, anxiety over a looming Reichstag Fire runs high. Even as I prepared this episode, a recent and horrifying chemical attack in Syria is suspected to be a false flag intended to trigger—or justify—American military action against the current Syrian regime, which Trump promptly and literally launched.

With so much meaning imbued in this event, it behooves us to examine it more closely as a “false flag.” Accusations that a conspiracy was afoot began almost immediately, as the Speaker of the Reichstag, Hermann Göring, whose residence stood across the street, straightaway formulated the opinion that the fire was the work of the embattled Communists and specifically the leader of the Communist Party in the Reichstag, Ernst Torgler. And even as the building burned, then-chancellor Adolph Hitler arrived at the scene, and on a balcony overlooking the conflagration inside the Session Chamber, lit by the glow of the fire and red-faced from the heat and from fury, is said to have remarked that it was the beginning of a Communist uprising. “Now we’ll show them!” he is said to have shouted. “Anyone who stands in our way will be mown down. The German people have been soft too long. Every Communist official must be shot. All Communist deputies must be hanged this very night. All friends of the Communists must be locked up.” And indeed, the night of the fire, the Berlin police and the Brownshirts were quite busy, kicking down the doors of thousands of Communists to drag them out of their beds and incarcerate them. Before long, the Nazis had charged four others for the firing of the Reichstag: Communist leader Ernst Torgler, who had been in the Reichstag late that night, and three little-known Bulgarian Communists, Georgi Dimitrov, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev.

The Nazi leaders at the scene of the fire. Hitler talking to Prince August Wilhelm, Göring (second from left) and Goebbels (second from right), from The Reichstag Fire by Fritz Tobias.

Almost simultaneously, the Communists of Berlin and beyond, as well as much of the foreign press, deemed it more believable to lay the blame for the fire at the feet of the Nazis themselves, a true false flag operation intended to make all of Germany fear a Communist uprising and provide pretext for the Nazis to declare martial law and bolster their governmental power. And indeed, the passage of the ominously named Enabling Laws, and most importantly the “Decree for the Protection of the People and the State,” soon gave credence to this suspicion.

On one item, at least, both sides of this argument could agree: Marinus van der Lubbe could not possibly have managed to set the Reichstag ablaze all by himself. Just based on common sense, almost everyone decided that he was either a madman or an imbecile, and details of the investigation that thereafter emerged only encouraged this assumption: an early communique relating the results of the police report indicated “that the incendiary material could not have been carried in by less than seven persons, and that the distribution and simultaneous lighting of the several fires in the gigantic building required the presence of at least ten persons.” The question, then, was who were the others, and which side had masterminded the act?

Communists abroad had no intention of waiting for the ruling of the German Supreme Court, which anyway they were certain they could guess. In solidarity with the defendants, then, who aside from van der Lubbe were widely regarded as innocent scapegoats, a book entitled The Brown Book of the Hitler Terror and the Burning of the Reichstag was published and a symbolic counter-trial was organized in London, with a variety of well-respected lawyers involved and various noteworthy intellectuals in attendance, including H. G. Wells.

The Brown Book and witnesses at the counter-trial took the low estimation of van der Lubbe’s character and ran with it, relying on a variety of never before cited sources to implicate the firebug as a homosexual prostitute and familiar of Brownshirt leader Ernst Röhm. The book also uncovered the fact that a tunnel existed beneath the home of Speaker Hermann Göring, crossing beneath the street and offering the likeliest means by which Nazi arsonists could have entered and exited the Reichstag undetected. Thus, the true incendiaries had escaped unseen and left behind their patsy, Marinus van der Lubbe, erstwhile Communist, perhaps, but in truth a Nazi stooge. This Brown Book, which was written anonymously but popularly attributed to none other than Albert Einstein, who always denied authoring it, presented a narrative of the fire that persisted for many years to come, such that many history textbooks reported as fact that Hitler certainly arranged the burning of the Reichstag himself, and even today many will repeat this story as accepted fact.

British Newsreel describing London Counter-Trial and German Supreme Court trial in Leipzig, via YouTube

After the counter-trial, the whole world, having witnessed the consolidation of Nazi power and the ruthless grinding out of Communist resistance in the wake of the fire, waited with bated breath for the outcome of the trial. But to the surprise of most, reports from the Supreme Court in Berlin indicated that the defendants were receiving a rather earnest defense and fair trial. Unusually, the proceedings found themselves bogged down in somewhat extraneous matters, as the prosecution, rather than just focusing on proving the defendants’ guilt, endeavored instead to defend the Nazis from the accusations of the Brown Book. When the trial did focus on the charges at hand, the issue under examination was whether van der Lubbe had any concrete association with the Communist Party leadership and fellow defendant Torgler in particular, which according to the court’s opinion the prosecutors failed to prove. The prosecution then had more than they bargained for when the Bulgarian defendant Dimitrov, who unbeknownst to them happened to be a high-ranking representative of the Communist International, took the stand. With sharp wit and clever logic, he turned every accusation back at the Nazis, holding up a figurative mirror so that every implied wrongdoing, every allegation of conspiracy and furtive crime became a fresh charge they had to defend against themselves. And while they succeeded with their parade of experts, who were in fact chemistry professors and criminologists with no practical expertise in fire assessment, to convince the court that van der Lubbe could not have acted alone, they failed to offer enough evidence to convict German Communist Party leader Torgler, international Communist leader Dimitrov or the other two Bulgarian defendants. Marinus van der Lubbe, however, who had stringently denied having accomplices throughout the proceedings and seemed to sink into black despair as the consequences of his actions unfolded, was convicted, and under a newly passed law that called for capital punishment in cases of high treason and arson, purposely made retroactive to apply to the Reichstag Fire case, he was beheaded within the year.

With the Supreme Court ruling that van der Lubbe did indeed have accomplices, the Nazis were at least able to maintain their insistence that their rule had been necessitated by the Red Peril. Meanwhile, the rest of the world—and, for the most part, historians—would side with the Communists and remain convinced that the Nazis themselves were the shadowy accomplices, and, ironically, their own tribunal, called on to condemn their enemies, had only served to prove the suspicions against themselves.

Marinus van der Lubbe at his trial, from The Reichstag Fire by Fritz Tobias.

Indeed, the ironies abound in this story, for not quite thirty years after the fire, an outsider to the world of academic history named Fritz Tobias, giving a sober and balanced look at all surviving documents, would prove to the world that Marinus van der Lubbe was indeed the sole arsonist, and his reckless act of political indignation, meant to wake up the common people to fight against the Nazi “mercenaries of capitalism,” had indeed ushered in the horrors of the Third Reich. Tobias’s work, which appeared in the German publication Der Spiegel in 1959 and which later he published under the title The Reichstag Fire: Legend and Reality, is a seminal work that changed history even if it failed to completely alter the public imagination when it comes to the fire, and I have relied on its remarkable details heavily in this account. Unfortunately, just as Tobias was attacked at the time as a whitewasher of Nazi history, in modern times his work has been embraced by Nazi apologists and holocaust deniers as proof the Nazis weren’t so bad. Because of that, while his work is available in its entirety in the form of a PDF online, the file appears to only be hosted by white nationalist websites spreading despicably racist ideology. Therefore, I have decided to host the file on my own website in an effort to make it available while also divorcing it from such associations.

In his work, Tobias systematically dismantles the prevailing narratives of not only the Nazi theory of Communist culpability but, more importantly considering its widespread acceptance, the Communist theory of Nazi culpability. He goes into minute detail describing the night of the fire, showing how the night watchman and others, like the Reichstag postman, had walked through the building minutes before witnesses saw van der Lubbe breaking in and had seen no one, smelled no petroleum or smoke. He demonstrates the fundamental unlikelihood that anyone entered the Reichstag via the underground passage because it was a labyrinth of locked doors and steam pipes with a floor of loose metal plates that made such a clamor when someone walked on them that the night watchman surely would have heard anyone passing through it. He examines van der Lubbe’s life, relying on the testimony of those who actually knew him and dissecting the testimony of those who didn’t to show he was no homosexual, no madman, no imbecile, but rather an intelligent young man, disgruntled due to unemployment, who not only was capable of setting the fire exactly how he said he had done it but who also had set fire, all by himself, to a number of other public buildings in the preceding days: a welfare office, the Town Hall and the old Imperial Palace. Moreover, he provides evidence that the early communique’s estimation of seven to ten arsonists was not based on any evidence but rather made on Göring’s insistence, for political reasons, and he debunks the testimony of the so-called experts at the official trial to establish that van der Lubbe not only could have started the fire himself but that he absolutely did. Furthermore, he reveals the true mind behind the Brown Book and the London counter-trial to be none other than Wilhelm Münzenberg, the head of Agitprop, or the Communist Agitation and Propaganda Department, in Paris. Indeed, Tobias goes through every charge in the Brown Book, showing it to be an outrageous tissue of lies and forgeries invented not only to indict Nazis for starting the fire but also to further the Communist cause. And he reveals the counter-trial to be a farce, with comical language barriers, Communist agitators pretending at unbiased judgment, bored officials checking out girls and even one witness who actually wore a mask on the stand in order to pretend to be a Storm Trooper with inside knowledge of the arson, when in fact he was a Jewish journalist.

Fritz Tobias, via the blog of an acquaintance and fellow Reichstag Fire researcher.

Predictably, Tobias was condemned for defending the Nazis, but with time and considered reflection on his work, the historical community at large realized that his was the most measured, realistic and convincing account of the Reichstag fire. Other historians, both professional and amateur, have since tried to resuscitate the theory of Nazi culpability for the fire, including most recently a book by Benjamin Carter Hett in 2014, but none of their attempts have succeeded in supplanting Tobias’s version of events in academic circles as they appear to rely solely on rehashing old speculation and second-guessing the credibility of Tobias and his sources rather than offering actual evidence.

In 2008, Marinus van der Lubbe was posthumously exonerated, but this was a purely symbolic gesture not reflective of his actual guilt in the crime. It was meant more to represent the modern sentiment that any criminal convictions made under the auspices of National Socialism must not have been an expression of justice, as Nazism itself represented the antithesis of justice. And still there are many who believe that we should not dare suggest the Nazis were innocent of any particular offense among their litany of crimes. In truth, acquitting the Nazis of this specific crime in no way excuses their manipulation of the event as an opportunity to seize power. Indeed, one can certainly imagine them perpetrating such a crime. Take for example their attack on the radio station at Gleiwitz in 1939, which many consider a false flag as it was meant to be blamed on Polish troops, and to ensure this, they are said to have taken concentration camp prisoners, murdered them with injections, dressed them in Polish uniforms and left them on the scene (although this too is disputed). The fact that they failed to plant such brazen evidence at the Reichstag, that they appeared by all reports shocked and angry upon learning of the fire and that they then put their supposed suspects on trial rather than summarily executing them to control the narrative of their hoax all tends to show that they weren’t responsible for the arson. But the fact that Hitler seized on the opportunity with such gleeful alacrity, calling it a signal from heaven,” should serve as an even darker lesson to which we should never turn a blind eye. Whether or not events have been orchestrated in conspiracy, how a government reacts to them, how they use them to their own advantage to promulgate doctrines or advance agendas, must always be closely scrutinized. We cannot afford to wear blinders when it comes to our leaders’ machinations. We might not survive such a bout of historical blindness.

*

Thanks for reading Historical Blindness blog. Be sure listen to this episode of the Odd Past Podcast. Download numbers really help. If you enjoy the show and are fascinated by historical mysteries, check out my novel, Manuscript Found!. Just visit the Books page of the website for links to the book on Amazon, where it’s available in paperback and on the Kindle for a meager sum. The first of a trilogy that is mostly complete, this volume is a gripping yarn about a Masonic murder mystery and one of the grandest hoaxes ever perpetrated: the beginning of the Mormon Church. As always, you can support us by subscribing if you haven’t already, liking us on Facebook and following us on Twitter (where my username is @historicalblind), by telling friends and family about the show and by donating if you feel generous. On the Donate page of the website, you can give a one-time donation or find a link to our Patreon page where you can pledge a monthly amount. Either way you’ll get a shout out on the podcast! Thanks again for reading the Historical Blindness blog.