The Lincoln Legends - Part One: Larger Than Life

The United States of America has been in existence less than 250 years. That may seem like a very long time, but consider that this is only 10 generations, that we can trace back through only 10 forebears to find an ancestor who was contemporary with the nation’s founding, and it becomes clearer how very young this country is. Think about your parents, your grandparents, your great-grandparents, and you’re already a third of the way to conceiving the length of ten generations. Though the U.S. is older than many another modern nation in the Americas, in the grand scheme of history, and in comparison to countries elsewhere in the world, it’s still quite young. Nevertheless, during the course of these 250 years we have accumulated much history and much mythology, immortalizing more than one American leader in the public imagination. This process of eternalizing the country’s most powerful and influential persons is nowhere more clearly symbolized than in the memorial at Mount Rushmore, where the likenesses of four perennially popular presidents have been carved into stone: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln. If we can judge by the Presidential Historians Survey conducted by C-Span four times in the last 25 years, these remain the most popular, or rather the most highly ranked former chief executives based on leadership characteristics. The exception would be Jefferson, who consistently ranks seventh in the survey, replaced by Teddy’s fifth cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who has ranked third in the last three surveys, just under George Washington. In all four surveys, presidential historians agree that Abraham Lincoln is number one, ranking highest in such categories as Administrative Skills, Economic Management, Moral Authority, Crisis Management, the Pursuit of Equal Justice, and Vision. Some of these are no-brainers, as Lincoln is the man who rose to the challenge of preserving the Union in the face of Civil War and freeing the enslaved, setting in motion the long struggle for racial justice and equality that continues today. But more than these accomplishments, he is admired today as a peacemaker, as a gracious and empathetic politician, who reached across the aisle in assembling his cabinet, as described by Doris Kerns Goodwin in her classic book Team of Rivals. He is also held up as a genius of oratory and as an exemplar of the American Dream because of his humble origins. Despite rustic beginnings, born into a poor family on the American frontier, lacking formal education, Abe Lincoln taught himself, became a lawyer, an enthralling public speaker, and reached the highest office in the land through sheer bootstrappery. Then, of course, his tragic murder, which traumatized the country, led to his being viewed as a martyr, and martyrs tend to develop a halo of legend around them. One perfect example of this mythologizing of Lincoln relates to his humble birthplace. To be sure, he had been born in a humble log cabin in rural Kentucky. Lincoln himself confirmed as much. However, during the decades after his death, around 15 different sites were claimed to be the birthplace farm. The National Park Service only ever accepted one of these locations as genuine, and on it there stood a log cabin that was said to be the actual cabin in which Lincoln had come into the world. A temple was built to house this national landmark, and tourists visited it in droves over the years. Ten years after the Lincoln Farm Association was incorporated and work on this National Historical Park was begun, the Lincoln Logs were invented by architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, becoming a hit children’s toy. Lincoln was now synonymous with log cabins, and the authenticity of the cabin in Kentucky would not be questioned for nearly thirty years, when finally a historian questioned the provenance of the log cabin in an academic article. As it turns out, while the farmland may indeed have been the birthplace of Abe Lincoln, when it was purchased, there was no cabin there. The speculator who bought the land moved a cabin from a nearby property onto it, believing that it was the former Lincoln log cabin and had been previously moved off the land. Even if that were the case, though, in the wake of Lincoln’s assassination, this speculator disassembled the cabin and took it on a promotional tour around the country, reassembling it in various exhibitions, and between stops, it was disassembled again and again and stored with another exhibit, the supposed log cabin birthplace of Jefferson Davis. The fact is that the logs seem to have been hopelessly mixed up and interchanged before the Lincoln cabin was finally reassembled in the temple built to house it. In 2004, a dendrochronologist finally put the controversy to rest, confirming that the oldest tree used in the cabin dated only back to 1848, making them about forty years younger than Abraham Lincoln. Today, the temple still stands and draws visitors to Hodgenville, Kentucky, but the Park Service now calls it a “Symbolic Birth Cabin.” This itself is symbolic of our memory of Abraham Lincoln, remembered today as the greatest of American Presidents, but also misremembered and surrounded by myths and frauds. Unsurprisingly, as we will find, most of those myths surround his assassination and the conspiracy to kill him. The Secretary of War Edwin Stanton is said to have stated at Lincoln’s death, “Now he belongs to the ages,” but as we have seen over and over, the ages often change how we remember things, regardless of what really happened.

*

It must be acknowledged here that I don’t intend to discuss all the myths and legends and other supposed misconceptions surrounding Abraham Lincoln. For example, I don’t intend to examine the historical research Lincoln’s sexuality in any detail. In brief, some biographers have suggested that Lincoln was attracted to men and that he had a secret relationship with his longtime friend, Joshua Fry Speed, as well as one of his bodyguards. These ideas are based on speculations about his relationship with Mary Todd Lincoln, a few details about sleeping arrangements when Lincoln shared a bed with these men. The only direct evidence for it, a diary supposedly kept by Speed, is widely deemed to be a hoax. Likewise, I will not expend much effort looking into the rumors of Lincoln’s alleged romantic relationship with Ann Rutledge, which likewise was promoted by a writer who claimed to have discovered a diary that was forged. I may discuss these claims further in a patron exclusive, but for now, they serve only as further examples of how our memory of Lincoln changes through the ages, evolving with our greater understanding but also becoming muddied by misinformation. This has long been the case. The story of Lincoln’s romance with Ann Rutledge appeared just after Lincoln’s assassination, spread by Lincoln’s law partner, who may have promoted it specifically to hurt Mary Todd, whom he disliked. Many of the myths surrounding Lincoln’s personal life in fact have their origin in slanders made against him. Another is the notion that Lincoln was an illegitimate son, that his mother, Nancy Hanks, actually bore the child of one Abraham Enlow, in North Carolina five years earlier than Lincoln himself believed he had been born, and that Thomas Lincoln only took his mother in and raised Abe as his own. These claims of Lincoln having been a bastard first arose in mudslinging attacks when he was nominated for president. Some claimed he was an illegitimate son of other famous politicians, like John C. Calhoun or Henry Clay, but the most believable was the claim about Enlow, which gained currency decades after Lincoln’s assassination through oral traditions in North Carolina, which is a very academic way of saying gossip. However, the very existence of Abe’s older sister, who would be his younger sister if the rumors were true, and the records of Thomas Lincoln’s whereabouts during the time when he would have had to have been in North Carolina marrying a pregnant girl, and the fact than many other women named Nancy Hanks, different women from Abe Lincoln’s mother, have been found to have been living in North Carolina back in 1804-05, all goes to prove that this was little more than defamation. Stories like these feel inconsequential and too uncertain to pin down, but they do show how uncertainty has grown around Lincoln’s life in the years since his death.

A depiction of the Lincoln birthplace cabin, courtesy Library of Congress.

Myths surrounded not only Lincoln’s personal life, but also his inner life, his thoughts and feelings and views on important matters, and these too persist today. So for example, in recent times, a myth has surfaced that Lincoln actually owned slaves. While it is true that he inherited slaves from Mary Todd’s family, who happened to be the biggest slaveholders in Kentucky, and an affidavit was recently published indicating that he sold them instead of emancipating them, the reality is more complicated and doesn’t warrant a recasting of Lincoln as some sort of crypto-slaveholder. It is absolutely true that Lincoln made a lot of statements about the social distinction that slave ownership conveyed, saying once that “people who don’t own slaves are nobody,” and that he long aspired to be of the slaveholding class. It is also true that he had made a career for himself representing slaveholders as an attorney, often in legal actions relating to their attempts to recover fugitive slaves. He was, however, also known to defend those who harbored fugitive slaves. It has been pointed out that, at the time, it was typical for lawyers to accept the first client who approached them to obtain their services, regardless of their personal feelings. And these attacks on Lincoln hearken back to early attacks on his policies as his star rose in the Republican Party. Lincoln had been known for a decade as an abolitionist, but in 1860, the more progressive Wendell Phillips asserted that Lincoln was just not anti-slavery enough, that if elected, he would surely dither and do nothing to abolish the institution. It is true that Lincoln was a product of his time, that he did play politics when it came to presenting himself as an abolitionist and carrying out abolitionist policies, and that, as I mentioned before in my episode about the 1619 Project, he did believe that whites could not coexist in equality with freed slaves, that the best solution may be for freed slaves to be sent elsewhere, out of the country, to create their own colony. It may be that Frederick Douglass was accurate in his estimation that Lincoln “shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen.” Nevertheless, and regardless of all the political calculations that went into it, he did sign the Emancipation Proclamation, and he did write, at the time, “I never in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper. . . . If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.” The problem here is a great man, who did great things, was also just a man, with faults and flaws. Yet in remembrance of him, he is elevated and venerated like a saint, such that he is either presented as impossibly virtuous or surprisingly wicked, when really, like all of us, he was somewhere in between.

Like any saint, the story of Lincoln has been crafted by hagiographers, his life, especially his youth, mythologized. Unlike the Golden Legend of Catholic Saints, though, Lincoln’s legend took the very American form of the tall tale. Stories about Honest Abe’s integrity abound, about how he trekked miles to give a customer back the few cents he had accidentally overcharged them when he worked as a store clerk, or that, like George Washington, when asked by his schoolteacher whether he had broken the antlers of a buck’s head mounted on the classroom wall, he couldn’t tell a lie and confessed he had done so while showing off his amazing height to classmates. There is simply no evidence for the veracity of such tales, and their very fictive quality indicates their fictional nature. Perhaps the most obvious tall tale is the one that has Lincoln wrestling a bear like he was Davy Crockett or something. The fact is that he really was an accomplished wrestler in his youth. There are primary source documents that bear this out. But the closest indication we have that he ever came near a bear is a poem he wrote called “The Bear Hunt,” which maybe indicates that he himself went hunting bear during his frontier youth in Indiana. The hunt described in it, though, is conducted by riflemen on horseback, commanding teams of hunting dogs. In it, after the bear has been taken down, a mongrel hunting dog who had fallen behind suddenly appears and sets on the already dead bear: “With grinning teeth, and up-turned hair— / Brim full of spunk and wrath, / He growls, and seizes on dead bear, / And shakes for life and death.” This seems the closest Lincoln ever came to wrestling a bear, in his imaginings of a “conceited whelp,” a foolish dog that thinks himself responsible for taking the beast down. The fact is, though, that we don’t much know what kind of lad Lincoln was or what adventures he really may have had. Even if Lincoln had told such stories himself, on the campaign trail, for example, they may have been embellished or entirely made up for rhetorical effect. The bare facts we have are that, after moving from Kentucky to Indiana, his mother died. Though he appears to have preferred reading and writing to physical work, his father relied financially on his labor, and he grew strong. He took up wrestling, and another tale has it that he confronted a local band of ruffians, Clary’s Grove Boys, and earned respect in the community by besting the gang leader, but again, there is no telling how real this story might be. So removed from reality is the youth of Abraham Lincoln that some physical landmark is longed for to make it seem real, as we saw with the fake birthplace cabin. Also present at the Lincoln Birthplace memorial park is a site marked as the location of a certain tree, the “Boundary Oak,” that is revered as a “living link” to Abraham Lincoln because it is presumed he may have interacted with it in some way. Perhaps he read beneath it or climbed it, many have wondered, but the fact is that Lincoln was only 2 years old when the family moved to another cabin in nearby Knob Creek, making it quite unlikely that he had much interaction with that tree at all. Nevertheless, though the Boundary Oak is nothing by a stump now, it remains venerated, like the relic of a saint, and the same is true of other places from his life. The Boyhood Home at Knob Creek is another part of the historical park in Kentucky, and at the Soldiers’ Home Cottage, where Lincoln lived for much of his Presidency, there are similar myths. A certain copper beech tree on the grounds is called a Witness Tree because of claims that Lincoln sat and wrote beneath it, but when a core sample showed in 2002 that it was only 140 years old, this proved that it would have been little more than a sapling when Lincoln lived there.

19th century depiction of young Lincoln reading by the fire. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Perhaps the most visited sites associated with Lincoln are Ford’s Theatre, where he was shot, and Petersen House across the street, the boarding house where Lincoln was taken after the shooting, where he died. And it is here, at the violent end of his life that the most myths and misconceptions surround Lincoln, as we will see for the remainder of this series. One popular story promotes the idea that Lincoln had been having some sort of premonition of his death in the days preceding his visit to Ford’s Theatre. According to Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln’s close friend and bodyguard, the president had confided in him, mere days before his assassination, that he’d been greatly disturbed by a dream in which he’d been walking through the White House hearing people sobbing and weeping in another room. When he found the source of the sound, he discovered people gathered around a corpse lying in state. When he asked who it was lying dead in the White House, according to Lamon, one of the soldier’s guarding the catafalque told him it was “the President; he was killed by an assassin.” It’s quite a story, but it’s one that Lamon did not tell until after the assassination, which may have colored his memory of Lincoln’s dream. Moreover, it seems Lincoln himself didn’t think the dream was premonitory, as Lamon says he further explained that "In this dream it was not me, but some other fellow, that was killed.” Nevertheless, it is easy to interpret this as some sort of precognitive event, even if Lincoln himself did not view it as such. There is, however, a far simpler explanation, one that does not require us to believe in a clairvoyant President. That is simply that Lincoln was troubled. There is much scholarship about Lincoln’s supposed melancholy, exploring the widely held idea that the president struggled with lifelong depression. When viewed in this context, his dream might be considered the result of a preoccupation with death, a common symptom of depression. His melancholy seemed to surface in the wake of the deaths of loved ones, such as his mother and sister, and later in life, two of his four sons, and might therefore be interpreted as standard grief, but he was also known to suffer bouts of gloominess in the wake of especially bloody battles in the war, such as the Second Battle of Bull Run. If Lamon is to be believed about this dream Lincoln had, the President spoke about it only a few days before his assassination, and he said that the dream had occurred 10 days earlier. That would be very early April, 1865. During the last year, General Sherman had employed his “scorched earth” tactics during his March to the Sea, one of the most destructive periods of the war. And the very month before the dream, Sherman had clashed with Confederate forces in the Battle of Bentonville, the bloodiest battle yet to have been fought in North Carolina. Therefore, it is entirely possible that Lincoln was suffering a bout of melancholy at the time because of the terrible loss of life and destruction resulting from a war that continued to drag on, and that this depression manifested psychologically as a symbolic dream about murder within the White House.

It is not exactly surprising, after all, that Lincoln would have been preoccupied by thoughts of assassination. At the time the dream occurred, he was about to undertake a risky visit to the front, to Richmond, which was then being occupied by Union soldiers. Certainly there would have been many discussions about safety precautions while he was there. After all, he was no stranger to threats on his life. Just 4 years earlier, as President-elect Abe Lincoln was headed by train for his inauguration, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, who were then investigating the destruction of railroad property along Lincoln’s whistle-stop tour, purportedly uncovered numerous assassination plots against him. In order to get Lincoln to Washington safely, they kept a low profile on their trip, canceling appearances along the way. When the reason came to light in the newspapers, the Pinkertons and their claims of assassination plots were doubted, and Lincoln himself was ridiculed, portrayed as unmanly, sneaking about in a disguise like a coward. Nevertheless, the reality of assassination threats must have been impressed on Lincoln. In fact, just a year before his death, someone seems to have taken a shot at him. Lincoln was riding home to his cottage alone one summer night when he heard a rifle shot. His horse bolted, speeding him to the cottage and causing his silk hat to fly off his head. The next day, the two guards on duty went to investigate and found Lincoln’s hat on the road with a bullet hole through it. Lincoln reportedly dismissed the incident as a hunting accident, but it is telling that, afterward, he never again rode to the cottage alone and went instead by carriage, accompanied by soldiers. Surely these facts make a troubling dream about being assassinated far less astonishing and provide a simple explanation with no need to resort to claims of supernatural prognostication. In the ensuing days, however, it seems Lincoln’s spirits finally rose. Richmond fell, his visit to the front was a success, and on his way home, General Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Court House. Just two days later, he addressed an adoring public on the White House grounds, declaring “the reinauguration of the national authority” and speaking about conferring “the elective franchise upon the colored man.” In the crowd, not far from him, was a handsome 26-year-old, a celebrity famous for his Shakespearian acting. His name was John Wilkes Booth, and it was later testified by one with whom he conspired that when Lincoln spoke about giving those citizenship rights to Black people, Booth resolved to murder the President. One claim has it that he said, in that moment, “That is the last speech he will ever make,” but this seems to be a later embellishment of Booth’s actual remarks, which included a racial slur and a verbal threat to take Lincoln’s life. The night before Lincoln’s visit to Ford’s Theatre to see the acclaimed British play Our American Cousin, the city of Washington celebrated the end of the war with fireworks. That night, as he apparently shared the next day, Lincoln had another dream, one that he did believe was premonitory. He told his staff that he had dreamed of standing alone on the forward deck of a ship as it sailed toward a mysterious shore, and he said that he had had this same dream many times just before something important occurred in the war. Therefore, he was convinced that it meant something important was again about to occur. And though my skepticism encourages me to believe that the recurring dream, which of course never predicted his death when he’d had it previously, was simply a coincidence, his interpretation of it did turn out to be prescient.

Contemporary newspaper artist’s impression of Booth’s leap to the Ford’s Theatre stage.

It was Good Friday, April 14th, 1865. After meeting with his staff, Lincoln enjoyed the spring weather in an open air carriage ride with his wife, Mary, and according to her, he was like a new man, his spirit rejuvenated. He spoke about overcoming their grief for their 11-year-old son, Willie, who had passed away a few years earlier, about trying to bridge the gulf that had opened between them and finding a way to be happy again. “I have never seen you this happy,” she wrote in a note to her husband later that day, and that evening, they decided to take in a show, arriving late to Ford’s Theatre as their production was already underway. The players stopped when it was learned that the President had arrived, and the band played “Hail to the Chief” as he took his seat in the Presidential Box with Mary and his two guests, Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancé Clara Harris. It is here, at the very scene of the murder, that the myths and misconceptions about Lincoln’s assassination really begin to accumulate. Illustrations of the event have Booth firing his pistol point blank into the back of Lincoln’s head and then leaping over the railing and onto the stage like Erroll Flynn, breaking his leg in the process, but still enough in control of himself to deliver his dramatic one-liner, “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” or “Thus always to tyrants.” In reality, Booth was some four or five feet from the president when he entered the room, and he had to fire from the entryway, for if he entered further, Major Rathbone, who sat on a sofa near the entrance, would have seen him. We know Booth did not fire from point blank range for two reasons; one is that there were no powder burns observed on Lincoln’s head, and the other is that Rathbone heard the pistol’s report just behind him. He sprang up to seize the assassin, and was stabbed in his upper arm by Booth, who had also come armed with a dagger. When the shot was fired, Lincoln was actually leaning forward over the railing, making Booth’s shot extremely lucky. In all likelihood, the assassin had been aiming for the President’s back and had missed his shot. Rather than escaping by some deft leap to the stage, Booth actually became entangled in a flag draped over the railing, his spur becoming caught in its fabric making his awkward fall somewhat farcical, resulting in the cracked fibula. When he shouted out the Latin phrase, it was not some dramatic flourish. That phrase was actually the state motto of Virginia, and he followed it up by yelling, according to some witnesses, “The South is Avenged,” or “Revenge for the South,” making his motivation exceedingly clear. Then again, some witnesses heard him say “I have done it,” or heard nothing at all, so again, the truth of the matter is obscured. Despite the awkwardness of his getaway from the Presidential box, Booth made good his escape despite his injury, jumping on a waiting horse and riding to Maryland, where his co-conspirators waited. Exactly who was involved in this conspiracy and exactly what became of Booth at the conclusion of the 12-day manhunt for him has become the subject of much speculation, myth, and conspiracy theory, as we will see in the rest of this series.

The first doctor to examine Lincoln had him laid on the ground and searched him for wounds. When he found the bullet wound in the back of Lincoln’s head, he pushed his finger in, searching for a bullet he might remove. He felt none. After being resuscitated and stabilized, Lincoln was carried out of the theater and into the street, where the owner of the lodging house across the road offered a room. It was a very small room, 9 by 17 feet, with a typical spool bed, wooden framed with spool-shaped spindles and railing for the foot and headboards, and it was far too small for Lincoln, whom they had to lay across it diagonally. Two other doctors stuck their fingers in his head wound that night, likely worsening his condition, though this was common practice at the time. By morning, Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States, died in this bed that was too small for him, larger than life to the very end. During the night, his wife Mary and his oldest son Robert came to his bedside, and so too did several cabinet members and other officials, though few could be admitted into the room at the same time, it being so small. Afterward, Currier & Ives and several other printmakers began to sell lithographs of the scene of Lincoln’s deathbed, based on descriptions of those who had been to see him in Petersen House. These lithographs became hot sellers, such that they became a common feature of many American homes. And here we find an apt example of the mythmaking process. At first, the engravings made of the scene were relatively accurate, They might have portrayed the deathbed at the center of the room rather than pushed against a wall as was the case in reality, but this can be forgiven as a necessity of artistic composition. Strangely, though, as more and more such portraits were created, the scene changed. Lincoln’s youngest son Tad was added, though he had never been there, and when Mary Todd Lincoln became unpopular because she was too grief-stricken to attend state funerals or vacate the White House, she was removed from the scene even though she had been by her husband’s side. It was common to picture several officials surrounding the bed, even when they could not have fit into the room at the same time, and each portrait featured a different and growing assemblage, removing one figure when it was deemed more important to include another, such as Vice President Andrew Johnson, who had not previously been pictured but who would be pictured after ascending to the Presidency. The number of people in the room grew until it was absolutely absurd—one later print featured 47 men crammed into the room—such that the small room at Petersen House came to be called the “rubber room” for how much it would have had to stretch to accommodate everyone.

A good example of the “rubber room” portrayals of Lincoln’s deathbed in Petersen House, with 26 historical figures present with the dying president.

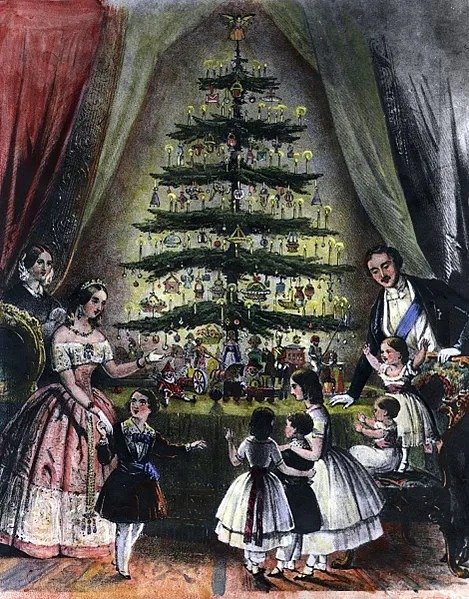

Many know the words spoken at Lincoln’s bedside as he took his last breaths, or at least, we think we do. It has been immortalized in countless history books that Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, wept as he said them: “Now he belongs to the ages.” Interestingly, however, some historians have begun to question this, suggesting that the quote has long been misreported and that Stanton actually said “Now he belongs to the angels.” There is actually a pretty strong argument for both, and we likely will never truly know which remark was uttered in the moment, but this dichotomy, between the idea of Lincoln belonging to history and of his being borne aloft by angels speaks further to the fact that he has consistently been mythologized since his death, venerated as a martyr, beatified like a saint, and even deified as a fallen god. Some of the later portraits of the scene in the rubber room at his death even began to portray angels above him, and the spirit of George Washington welcoming him to the heavens, or even to portray the godlike figures personifying Britain and America, Britannia and Columbia, visiting him at his deathbed. As we already saw, at the national park memorializing his birthplace, the symbolic cabin there is enshrined within a temple, as though pilgrims to the site are expected to worship him. And this deification of Lincoln is nowhere more apparent than at another pilgrimage site, the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial in Indiana, especially during the 30s and 40s, when it was slowly developed and constructed. Making much of the fact that Lincoln was killed on Good Friday, the comparison to Christ was explicit there, where the entire memorial was landscaped as a huge cross. In fact, until the sixties, the whole memorial was dedicated not to Lincoln himself, but to Nancy Hanks, his mother, who was venerated there as if she were another Virgin Mary. And between his mother’s grave and the replica of his boyhood cabin, the designers installed the Trail of Twelve Stones like the stations of the cross, each supposedly a stone taken from a place that represents an important location in Lincoln’s life—one from the White House, one from Gettysburg, etc. And it is not just these birthplace and boyhood memorials that engage in Lincoln worship. Even the most famous of his memorials, in Washington, D.C., is designed as a classical temple, within which his gargantuan statue, enthroned like a god, proves that he remains larger than life even in death.

Further Reading

Gopnik, Adam. “Angels and Ages.” The New Yorker, 21 May 2007. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/05/28/angels-and-ages.

Johnson, Kevin Orlin. “The Preacher Who Stole Lincoln’s Past–By the Carload.” Abbeville Institute, 7 March 2022, www.abbevilleinstitute.org/the-preacher-who-stole-lincolns-past-by-the-carload/.

Nickell, Joe. "Premonition! Foreseeing What Cannot Be Seen." Skeptical Inquirer, vol. 43, no. 4, July-Aug. 2019, pp. 17+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A593430322/AONE?u=modestojc_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=b71b0a30.

Sellars, Richard West. “Remembering Abraham Lincoln: History and Myth.” The George Wright Forum, vol. 11, no. 4, 1994, pp. 52–56. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43598880.

Steers, Edward, Jr. Lincoln Legends : Myths, Hoaxes, and Confabulations Associated with our Greatest President. The University Press of Kentucky, 2007.