A Very Historically Blind Christmas II: Father Christmas

Allow me to place this furry hat on your head, fill your hand with a warm cup of either mulled cider or eggnog, and lead you into the drunken revelry. Once you’ve had your fill of merry-making, let us warm ourselves by the fire and watch the snow fall outside the window. Settle in a comfortable chair as I share a remembrance of times long past and of the Christmases of yore. Those of you who joined me last year at this time may remember that we spoke of the ancient origins of this holiday. We spoke of midwinter festivities, of Saturnalia and the Kalends, as the origin of many traditions such as gift giving and decorating with greenery, and we looked back on Mithra and the celebration of Sol Invictus as the original December 25th holy day, long before Christianity placed Jesus Christ’s birth on the same day and made it a central part of their liturgical calendar, a day when the faithful are obliged to attend Mass. For much of the Middle Ages, the Christmas season was a time of conflict between ancient revelry customs and modern religious observance, with images of the Divine Infant, Santo Niño, the Christ Child, personifying the innocence and purity to which all should be aspiring in that time of debauched and licentious carousal. But the Christ Child was not not the only incarnation of the holiday. There is a long and rich tradition of the concept of Christmas being personified, of a figure embodying the holiday, whether it be a real person or a fictional figure, like a mascot, which of course we have today in the rotund and cherry-nosed character we all think of as Father Christmas. So refill your cup, cut yourself a slice of pie, and follow me back to Christmases past.

Stare into the flickering candle flame and follow it back to dawn of Christmas, to the midwinter celebrations of antiquity. Recall our discussions of Saturnalia, the mid-December Roman festival in honor of Saturn, which itself may have evolved from even older solstice traditions among farmers, and the Kalends, a kind of New Year’s festival that followed. We see the decoration of homes and public places with greenery, and the giving of gifts in the form of cerei candles. And as today, it was a time of merrymaking, but the way we think of making merry during the season today may be a bit more tame than Romans thought of it then. As the celebration represented the death inherent in winter followed by the rebirth of light and warmth and hope, as symbolized by the common sight of lit candles, it was a true carnival, in the sense of the word meaning “a farewell to the flesh.” It was an occasion of wild and riotous excess, with not only feasting and music and dancing, but drunkenness and gambling and promiscuity. Saturnalia and the Kalends were times when the norms of society were rescinded and social order upended. Slaves not only ceased their work; they sat at the head of their masters’ tables, raised briefly to a station in life they could never enjoy on any other day of the year. This tradition of inebriation and topsy-turvy social order persisted in midwinter seasonal celebrations long after the Fall of Rome and the rise of Christianity, with not only the rich and poor trading places, but also men dressing as women. Mid-December remained a time for debauchery and reversing the social order all through the Middle Ages and into the Early Modern period. In England, the custom of wassailing appeared, the word evolving from a Middle English toast to one’s health or wholeness. Wassail bowls were popular for communal drinking, and as wassailers often went house to house singing and offering drinks from their bowls or asking that their bowls be filled, it appears to be a forerunner of Christmas caroling. But eventually wassailing became for some an opportunity for thuggery in this topsy-turvy season, and wassailers were sometimes known to force their way drunkenly into homes demanding to be given food and drink. Considering this, as well as the wanton behavior that resulted in a boom of bastard September children every year, it is perhaps no surprise that Puritans outlawed Christmas celebrations in the mid-1600s, both in England under Cromwell and in New England, under the Puritan government of Massachusetts.

Photogravure of a drawing depicting a drunken reveler being carried away by his friends during the Saturnalia, c. 1884, via Wikimedia Commons

To better understand why Puritans might reject such Christmas traditions as further examples of the Catholic Church’s decadence, it must be clarified that such customs were not only practiced by pagans or the godless. The church also took part in these bacchanals, in the form of the Feast of Fools, a tradition among medieval clergy in Western Europe in which low-ranking clerics took over their churches, holding mock services in which they dressed as choir women, sang indecent songs, burned old shoes as if they were incense, gambled danced among the pews, drank themselves silly, and even went out upon the town making lewd gestures, laughing drunkenly, and generally raising hell and making spectacles of themselves. Beyond the debauchery, one particular tradition hearkens clearly back to Saturnalia, and it is here where we first begin to see the Christmas season embodied in a figure. At Saturnalia, a mock king was sometimes raised up to preside over the festivities, and we see this custom echoed throughout history. During the Feast of Fools, on December 28th, Holy Innocent’s Day, a choirboy was chosen to take over as bishop for the day, complete with small robes and jewelry made specifically for this so-called Boy Bishop. Likewise, during festivities of Twelfth Night, the end of the Twelve Days of Christmas, a cake was shared by all, and he who received the slice into which a bean had been baked was pronounced the Bean King and would then preside over the party, choosing a queen and naming other party goers to positions in his mock court. This tradition of mock kings at Christmas time is again further echoed in the late medieval and Renaissance custom of appointing a Christmas Lord to preside over the seasonal merrymaking. This Master of Merry Disports, as he was called, or otherwise, this Abbot of Unreason, or most commonly, Lord of Misrule, acted as a kind of host for all the dancing and mummery, the masquerades and feasts, leading motley groups of merrymakers through the streets and into churches, ringing bells and singing. These roles, filled by random men or children from a variety of socioeconomic classes, represent perfectly the embodiment of the old ways of Christmas, of topsy-turvy role reversal and reckless jollification. But for the history of the character that embodies Christmas as it is celebrated today, we must look at far more recent history.

Feast of the Bean King, c. 1640-45, via Wikimedia Commons

Today, when one thinks of Christmas personified, one doubtless thinks of Santa Claus, that jolly old gift giver with his own elaborate mythos. Now parents, if your children happen to be within earshot, you may want to put in earbuds so that they don’t learn all the secrets of Santa before he wants them to. ...OK, if the little ones are no longer listening, I’ll continue. To fully grasp how the fictional character of Santa Claus was invented, and what historical basis there may have been for him, we must actually begin in early 19th-century America and that inventor of enduring myths, Washington Irving. Many know Irving for his composition of Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, a perennial Halloween favorite, and I spoke last year, around Columbus Day, about his role in creating some of the myths surrounding Christopher Columbus as well. Some may not be as aware, however, of his part in mythologizing the figure of Santa Claus. In 1809, Irving wrote A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker, a satirical look at New York life narrated by a fictional Dutch historian. It was through this book that he introduced a character from Dutch folklore to American culture, the figure of Saint Nicholas, called Sinter Claas by the Dutch, a much venerated and mythologized Greek miracle worker whose cult had spread across numerous European countries since his death in the 4th century CE. Across most of Europe, he was the patron saint of childhood, but in Irving’s History of New-York, Knickerbocker presented him as the patron saint of New York, and thereafter, others took the idea and ran with it. The next year, 1810, one John Pintard, the founder of the New-York Historical Society and a big proponent of public holidays commemorating history, having helped establish the 4th of July, Washington’s birthday, and Columbus Day as holidays, decided to observe St. Nicholas Day, the feast day of the Saint, on December 6th. New York was an economically divided place that saw class unrest during the holidays, and he envisioned his banquet as an opportunity to resurrect the ancient topsy-turvy traditions, when the poor and the rich dined side by side. Pintard commissioned a poster for his banquet that depicted “Sancte Claus,” but St. Nicholas had not yet taken the form of Santa as we know it today, looking more like an ascetic clergyman, slender and barefoot in a tabard.

Broadsheet depicting St. Nicholas as “Sancte Claus,” by John Pintard, 1810, via Wikimedia Commons

Some eleven years later, in 1821, Irving revisited his History of New-York, and its second edition shows either some new inventions of Irving’s or reflects the changing image of St. Nicholas in America during the intervening years. Irving describes him smoking a pipe and bringing presents to children in a magical flying wagon that soars over the treetops. Then, St. Nicholas took his essential and final form a couple years later, with the December 1823 publication of the poem “’Twas the Night Before Christmas” in an upstate New York newspaper. For more than 150 years, this classic poem, originally titled “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” was attributed to Clement Clark Moore, who legend has it composed the piece during a sleigh ride into lower Manhattan to buy a turkey for Christmas dinner. A literary poet and classical scholar, Moore thought it mere doggerel and wouldn’t have his name attached to it for twenty years. However, in 1996, the literary sleuth Don Foster made the convincing argument that it was actually penned by judge and amateur poet Henry Livingston, Jr., whose surviving work far better matches, in tone as well as meter, the poem in question. But regardless of who wrote the poem, Santa Claus had arrived in all his particulars. Irving’s flying wagon full of gifts had become a sleigh, and it now was hitched to reindeer, each with a name. St. Nicholas descended through the chimney to enter homes by the hearth, where stockings had been hung for him to fill with gifts. Here we see the universal modern image etched forever in verse: the rosy cheeks and red nose, the droll smile and white beard, the rotund figure dressed all in furs. Only one particular seems to have been ignored in subsequent iterations: in the poem, he is a small elf, his conveyance a “miniature sleigh and eight tiny rein-deer.” As his legend grew, so too did his size, and the elfin element of the legend does survive, of course, in Santa’s army of elf tinkerers at the North Pole. With the small exception of his stature, the figure of Santa Claus seems to have leaped from the imagination of 19th century New Yorkers fully formed. But that is not in fact the case. They built upon an existing mythos surrounding the figure of St. Nicholas, and they incorporated elements from traditions surrounding other seasonal figures in European folklore, all of which we must explore in order to fully grasp the origins of the character we call Santa Claus.

The notion of St. Nicholas as an elf, and later of elves toiling in his service at the North Pole, seems to have been a clear syncretism of folkloric traditions. Elves and faeries have long been associated with Christmastime, stretching all the way back to Scandinavian antiquity. Icelandic tradition holds that the thirteen Jola-Sveinar, sons of a troll named Gryla, arrived in households one at a time during the Yuletide and departed just as slowly, playing pranks and stealing food and sometimes abducting naughty children. These Christmas elves are mirrored by the Swedish Jultomten, the Danish Julnissen, and the Finnish Joulutonttuja, Yuletide elves known to either reward or punish, for whom householders left out offerings of milk and porridge, as well as tobacco and booze. Over time these Christmas elves came to be represented much like modern day garden gnomes, white-bearded with a pointed hat, which seems to be a clear inspiration not only for the diminutive stature of the “jolly old elf” in the famous aforementioned poem, but also for the modern image of Santa Claus and our annual offerings of milk and cookies. Another influence on the image of Santa Claus was the English folkloric character of Father Christmas, also called Sir Christmas, a robust and bearded character dressed in a fur-trimmed robe that appeared in the late Middle Ages as a symbol of the season. Perhaps the most famous iteration of this character was the Ghost of Christmas Present in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. But not all the folkloric and mythological characters from which Santa Claus evolved were so recognizable. For example, much of his legend appears to have been borrowed from ancient winter goddess traditions out of Northern Europe. Longtime listeners may remember one of the digressions I took while discussing white lady ghosts in Germany years ago. That rabbit hole led me to the goddess tradition of Berchta, or Perchta, the spinner, a spirit who took great interest in matters of the household, a disheveled witch-like character who inspected homes for cleanliness, rewarding the diligent children who kept houses neat and punishing the indolent and naughty children who made messes. Berchta flew through the night skies during the Twelve Days of Christmas, accompanied by phantom creatures and ghost children, entering homes to make her judgment on the family’s industriousness, and to rock babies in their cradles. If the members of a household did not placate her by leaving out the remnants of a special dish, then it was said she cut open their stomachs as they slept and ate her fill of their undigested meal. There were numerous versions of this winter goddess Berchta or Perchta, including Hertha, Bertha, Holde, Holda, Holle, and later iterations like the German Frau Gaude. In some variations, the goddess was said to gain entry into homes via the smoke of a hearthfire. Therefore, we have in her a figure who enters houses through the chimney, who expects a treat to be left out for her, and who rewards or punishes children based on naughtiness.

Depiction of Perchta accompanied by spirits, 1863, via Wikimedia Commons

While all of these elements give context for the idea of a gift-giving supernatural spirit, an elf or gnome or goddess or witch, that visits children at Christmastime, how did such pagan traditions come to be associated with St. Nicholas, the namesake of Santa Claus? We know very little of the figure called St. Nicholas. He was born sometime around the late 3rd century in southwest Asia Minor, probably in the city of Patara, in the district of Lycia, and eventually became the bishop of Myra, in what is today Demre, Turkey. He survived the persecution of Christians in the area during the first several years of the 4th century, and he was said to have attended the Council of Nicaea, although some historians have found that his name did not start appearing on lists of those who attended the Nicaean council until the Middle Ages, after he had become a popularly venerated figure. While at first and for a long time, his veneration as a saint was limited to only his homeland, eventually it spread across Europe, with his feast day of December 6th probably memorializing the day of his death. Today, because of the vast legendarium that has grown around his life, he is without doubt the most famous saint in existence, and in these legends can be seen some seeds for the legend of Santa Claus as we know it today, as well as influences from some of the pagan traditions that already existed in the countries where his legend spread. But not all the stories about St. Nicholas can be seen to connect to the Santa Claus story. Some were merely the acts of a godly man, and some miracles attributed to him by his cult seem like the common fodder of hagiographers. For example, Nicholas of Myra is said to have confronted a group of thieves and convinced them to return their stolen goods, a story that led to “clerks of St. Nicholas” becoming a medieval euphemism for thieves. Then there were multiple tales of St. Nicholas stopping innocent people from being executed for crimes they did not commit. One involved standing up to Emperor Constantine when he wanted to execute three soldiers for disloyalty, and another had Nicholas intervening by seizing the sword of a soldier who was about to behead an innocent man. Furthermore, Myra being a port town, many prayers were directed toward safe passage for their sailors and the grain they carried. Many of the older traditions surrounding St. Nicholas as a wonderworker have him performing miracles at sea, as a guardian of seafarers. One legend tells of Nicholas calming a storm during a voyage to the Holy Land, and others suggested that St. Nicholas saved the lives of sailors who called to him for help, making him something of a patron saint of sailors. Indeed, some depictions of Nicholas have him riding a white horse that symbolized the froth of a cresting wave, much like the pagan sea god Poseidon, leading to speculation that the cult of St. Nicholas was absorbing pagan traditions long before the Middle Ages.

Many have looked for connections to Christmas traditions in the legendarium of St. Nicholas, and some of the connections that have been made are dubious, such as the claim that Nicholas was so young upon becoming bishop of Myra that he was called “the Boy Bishop,” a claim for which there appears to be no support beyond the fact that boy bishops were customarily chosen on St. Nicholas Day. But one begins to get an inkling of the eventual course his legends would take when one hears the tales that cemented his reputation as a gift-giver and patron saint of children. The central story of his legendarium in which the tropes of Santa Claus can be seen is the story of the three maidens. In this tale, which seems to have originated in the 8th century, long after his death, a young Nicholas is said to have become aware that three virtuous young ladies faced a terrible fate. They were of age to marry, but because their father could afford no dowries, he intended to sell them as prostitutes instead. Springing into action, Nicholas, who apparently had plenty of money, secretly crept up to the man’s house at night and tossed a bag of gold through an open window. The gold made it possible for the man to marry off his eldest daughter, and the next night, he was surprised to see another bag of gold fly through his window, enabling the marriage of his middle daughter. On the third night, when a third bag of gold was thrown into the house, the father raced outside and caught Nicholas in the act. He thanked Nicholas profusely, but Nicholas asked him to keep his gifts secret. Later versions of this story claim that Nicholas climbed onto the roof and dropped the gold through the chimney, which may in fact be a syncretization of the Nicholas legend with that of Berchta entering homes through chimney smoke. Some variations have it that Nicholas’s gifts of gold fell into some stockings that had been placed by the fire to dry, thus resulting in the tradition of Christmas stockings, but this too may be the result of syncretism, as some scholars have pointed to ancient Norse Yuletide traditions as the origin of Christmas stockings. During the Yuletide, Odin was said to ride through the skies leading his Wild Hunt, and children who filled their shoes with straw or carrots to feed Odin’s horse Sleipnir might in the morning find their shoes full of candy and gifts to repay their kindness. But regardless of whether these particular traditions originated from legends about St. Nicholas or were incorporated from pagan traditions, we do know that Nicholas was associated with charitable and secret gift-giving, such that, after his death, it became common when any gift was received from an unknown source to attribute it to St. Nicholas.

“The Story of St Nicholas: Giving Dowry to Three Poor Girls” by Fra Angelico, c. 1447-48, via Wikimedia Commons

Indeed, death did not halt the growth of St. Nicholas’s legendarium, for some of his most famous miracles were said to have been performed from beyond the grave. In one story, when a Christian man swore by St. Nicholas to repay a loan to a Jewish moneylender but then tried to cheat him, St. Nicholas took notice. The moneylender took the Christian to court, and the debtor brought a hollow staff full of gold, which he handed to the moneylender before swearing he had given back all the money to the lender--a technical truth since he had given the lender his staff to hold. Afterward taking back his staff, he went on his way, but the spirit of St. Nicholas caused a cart to run him down in the street and break open the staff, revealing the gold. The Jewish moneylender refused to take the money, however, because he did not think the man deserved to die, but when St. Nicholas raised the cheating debtor back to life, the moneylender converted to Christianity. After this, Nicholas came to represent fairness in financial dealings and became a patron of moneylenders. The three bags of gold he gave for the three maidens became three balls of gold, a symbol taken up by the Medici banking family in Renaissance Italy, and an icon that can be seen even today decorating the establishments of that most common of modern moneylender: the pawnbroker. Thus St. Nicholas has as part of his character a sense of justice, rewarding the good and punishing the wicked. Then there is the legend that truly cemented his reputation as a guardian of children: the story of the Three Students. This medieval tradition out of 12th-century France holds that a wicked innkeeper received three young men who were traveling through his region, and while they slept, he murdered them so that he could take their money. The innkeeper chopped the students into pieces and packed their dismembered corpses into pickle barrels, and he would have surely escaped justice for this heinous crime if St. Nicholas had not been watching from on high. The story tells us that Nicholas made the students whole again and resurrected them. Over time, these young students were depicted more and more as children, just as the three maidens were depicted more and more as little girls, and St. Nicholas’s reputation as not only a bringer of gifts but as a protector of children was complete. All he needed now were Odin’s fur coat and hearty frame and the twinkling charm of an elf, both of which he collected as his legend spread through pagan northern Europe.

From La Légende du Grand Saint Nicolas, published by the Société de S. Augustin, Desclee, De Brouwer & Cie., Paris-Lille-Bruges, ca. early 1800s, via StNicholasCenter.org

Today, St. Nicholas enjoys an odd position. Through the evolution of his legend and the corruption of his name, he has become a universal symbol of Christmas as Santa Claus, and many still celebrate his name day to remember him as a saint. However, the Roman Catholic Church has always had a conflicted relationship with Nicholas. His veneration predated any official canonization process, and it has been suggested that some in the church are put off by the saint’s popularity, especially insofar as he seems to have eclipsed the Christ child in his embodiment of Christmas. Indeed, one of his names, Kris Kringle, appears to have derived from Christkindel, a word for the baby Jesus, so it seems the gravity of the legendarium of St. Nicholas is such that it pulls in not only pagan traditions but Christian ones a well. It is a snowball that started rolling in the 4th century and has grown to become a massive, unstoppable folkloric force that assimilates everything in its path. Perhaps in an attempt to resist this relentless legend, as part of a 1969 revision of its calendar of saints, the Roman Catholic Church made veneration of St. Nicholas optional, but the saint remains an important figure in both the Anglican Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. In fact, in 1972, after reducing St. Nicholas’s position, the Roman Catholic Church gave the bones and other relics of the saint to the Eastern Orthodox Church. Today, the supposed remains of the saint who became Santa are kept in New York, a fact that the myth-maker Washington Irving and his fictional narrator Diedrich Knickerbocker would truly appreciate.

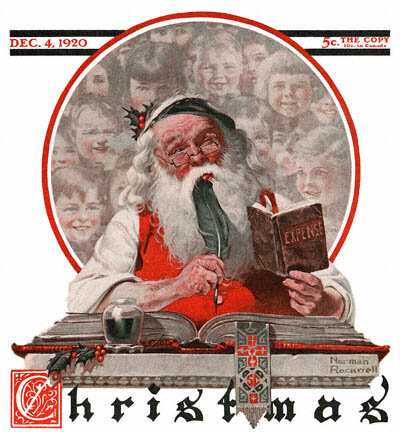

Saturday Evening Post cover by Normal Rockwell, 1920, via Wikimedia Commons

Further Reading

Elliott, Jock. Inventing Christmas: How Our Holiday Came to Be. Harry M. Abrams, 2002.

Flanders, Judith. Christmas: A Biography. St. Martin’s Press, 2017.

Gulevich, Tanya. Encyclopedia of Christmas. Omnigraphics, 2000.

Kelly, Joseph F. The Origins of Christmas. Liturgical Press, 2004.