The Lost Colony and the Dare Stones, Part One

Welcome to another installment of Historical Blindness! I’d like to start by thanking all the listeners who checked out our first installment, and I’d like to heartily apologize for the amount of time between our first post and this follow-up. The fact is that the practical matter of earning a living and providing for my beautiful wife and daughter leaves me with little spare time to work on this project. If you enjoy this blog or its associated podcast, please consider making a donation to support its production. Listener support would make it possible to compose and release this podcast on a more frequent basis. I’ve made it a bit simpler to donate by setting up a page on our website at www.historicalblindness.com/donate, where you’ll have the option of making a one-time donation or pledging regular support through Patreon. You can navigate to the page by finding and clicking the Donate button above. Thanks so much for any support you can offer!

In this two-part installment, we’ll explore one of the creepiest and most mythologized mysteries in American history, and we’ll dig into one of the most consistently debated, debunked and disputed archaeological finds of the last century. Our mystery, of course, is that of the Lost Colony of Roanoke, the fate of its denizens, and the further puzzle of the notorious Dare Stones.

This topic is exemplary of the kind of subject matter I hope to explore most in this podcast: a story that is compelling and atmospheric, evoking an air of mystery and presenting an enigma while provoking questions and doubts about the reliability of the historical record. This is quinessential Historical Blindness.

Much has been made of the Lost Colony of Roanoke in popular fiction and entertainment, especially in the horror genre. Stephen King himself played with a parallel to the Lost Colony in his nightmarish novel It. Most recently, the popular television series American Horror Story, which had previously played with elements of the story, focused on it more directly in its sixth and current season.

Something about the setting of the story makes it unsettling from the beginning. In 1585, when England first sought to establish a permanent colony in the Americas, it was a mystery continent, very literally a New World with new peoples, unfamiliar races, unusual foods, strange creatures—an alien world with harsh seasons of unforgiving weather and scarcity, fierce natural predators and inscrutable inhabitants, any of which would kill visitors and settlers alike. It was a place and a time, as well, when magic and supernatural evil were living realities, at least in the minds of those who lived the in the era, European and indigenous alike.

Consider, then, the discovery made by John White, governor of the colony, against this backdrop, when upon returning after too long an absence to resupply the settlers, he discovered all the colonists, including his daughter and granddaughter, vanished and the only clue left behind a curious word carved into a post. That word, now infamous and fraught with sinister connotation: Croatoan.

But to gain some perspective on this much embroidered story, we must examine its beginnings. The colony of Roanoke was first established, upon an island in what was then considered Virginia—named for the Virgin Queen Elizabeth after initial voyages of discovery chartered by her pet, Sir Walter Raleigh—but in what today is North Carolina, south of Albemarle Sound between the mainland and the barrier islands called the Outer Banks. The Queen had been pleased by reports of the island’s climate and beauty and the amicability of its natives. Therefore, England sought to establish its first American colony there, in direct competition with the colonial ventures in Florida of their naval rivals, the Spanish. Before the establishment of the Roanoke colony that we now think of as the Lost Colony, there had been previous attempts to settle on the same island. Sir Walter Raleigh dispatched a fleet carrying a group of 108 settlers to the island in 1585, which along the way perpetrated some raids and depredations in the Spanish West Indies before being hosted cordially by the Spanish governor of Hispaniola. Thereafter, on their way to Roanoke, they explored the island known as Ocracoke south of Cape Hatteras and, in retaliation for an alleged petty theft, burned a native village to the ground. After establishing their colony on the northern part of Roanoke Island, the fleet granted one Ralph Lane the governorship and returned to England for resupply. Lane was busy in the absence of the fleet, building a fort on the eastern coast of the island and exploring the coast of the mainland. However, because of the lateness of the season when they arrived and their unfamiliarity with the land, they failed to raise any crops and quickly ran through their provisions, which meant relying wholly on native charity. This, of course, led to privation and poor relations, and while the colonists survived their first winter, in 1586, their position seemed increasingly tenuous. After a minor clash with the local tribe in May, the English retaliated with a raid in which they overturned canoes and decapitated two natives. This, of course, resulted in open warfare, which concluded with the murder of the tribe’s chief.

Still awaiting their resupply nearly a year after the fleet had left the colonists on the island, it was with great relief that they received the news of Sir Francis Drake’s formidable fleet laying not far offshore. Lane predictably pleaded for aid, suggesting their position among native tribes was untenable, a plea that was carried to Drake. Upon receiving two options from Drake, that of accepting a ship and further provisions that would supply them for the foreseeable future or boarding the fleet for immediate passage back to England, Governor Lane, not wanting to abandon the colony quite yet, was disposed to accept the ship and supplies. However, as the first, smaller ship Drake offered was promptly lost in a storm and as any other ship Drake might offer would be too large to harbor in their island port and would have to anchor beyond the Outer Bank, making it indefensible, Lane and the colonists erred on the side of caution and abandoned their colony, leaving only 15 men behind to literally hold the fort. Shortly thereafter, their resupply finally arrived to find the settlement all but deserted. Thus even the very first colony of Roanoke was lost, though under far less mysterious circumstances.

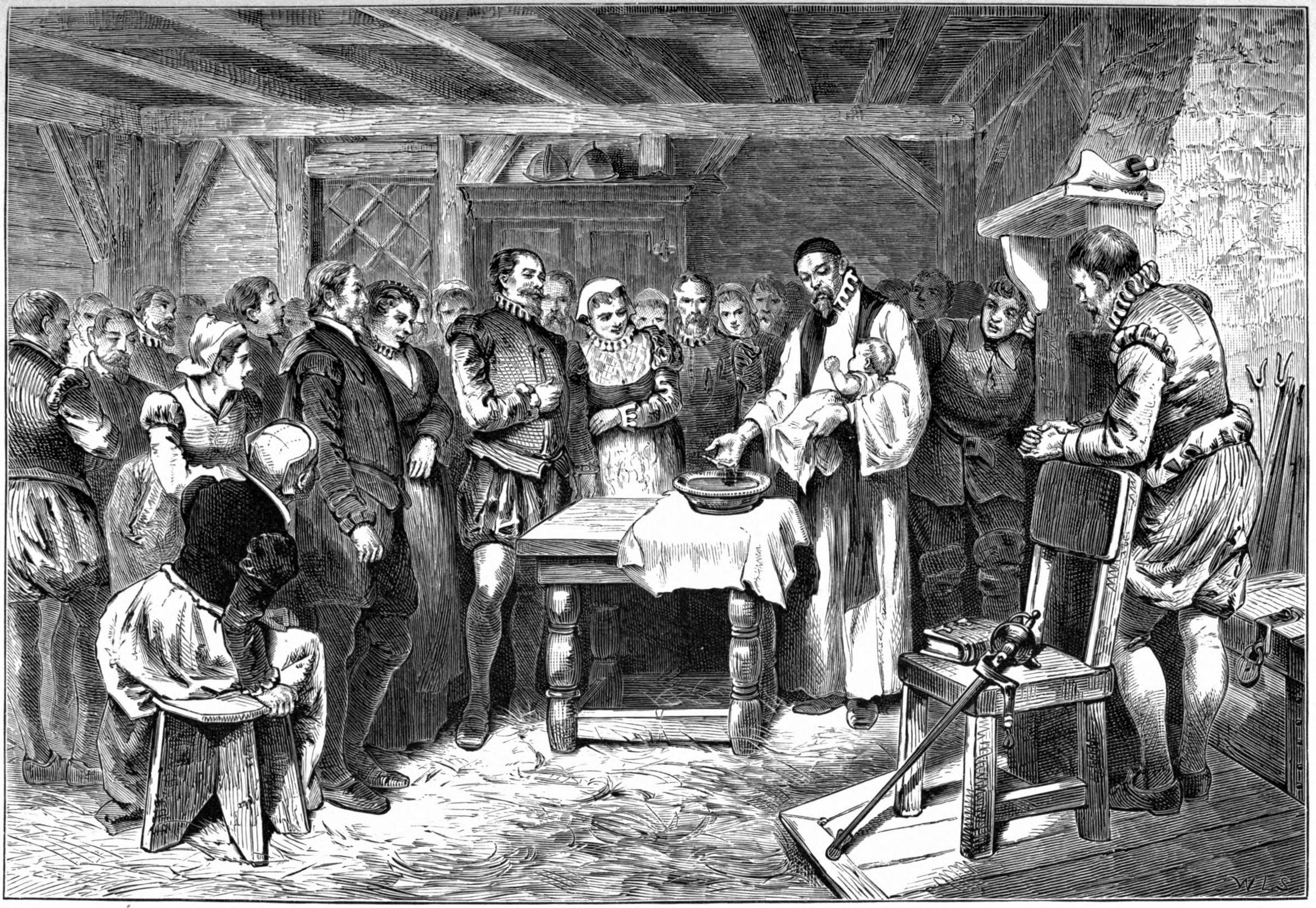

Another colony was not established at Roanoke for a year, this one to be governed by John White, who as a young artist had been among the fleet that established the first colony there. Among the 150 settlers with whom White sailed across the Atlantic were his daughter, Eleanor, and son-in-law, Ananias Dare. The journey to the New World was known to be dangerous, or at least arduous, taking a minimum of six weeks. In this case, it took almost three months during the summer heat for White’s small fleet to reach Roanoke. Therefore, it is surprising that White consented to let Ananias bring Eleanor, for she was pregnant, and must have been far along and well aware of it when they embarked in early May, for less than a month after disembarking at Roanoke in late July, she gave birth to her daughter, whom she named Virginia after their new home.

Virginia Dare came into the world as both a person and a symbol. She was the first English child born in the New World and thus came to represent many things to many people. She was a symbol of hope and rebirth, emblematic of the human spirit of exploration and adventure as much as of British expansionism and willpower. She has since passed into folklore as an icon of American history, representative of our nation’s independence and our bravery. Moreover, as a child, she is a figure of innocence and virtue, and as a woman, a remarkable and empowering character.

The colonists’ intention had been to found their so-called City of Raleigh on the Chesapeake Bay, where access by ships of a deeper draft would be more feasible. First, though, they landed a party on Roanoke to check on the fifteen men left behind the previous year. None were found, but they did discover the skeleton of one man and the ruins of their fort, which had been burned to the ground. It was assumed, then, that they had all been slain by “Sauages,” but finding the many dwelling places still standing, as well as melons that had grown well in the settlers’ absence and an abundance of wild game, the new expedition decided to remain despite this ominous portent.

Shortly after the new colonists settled there, some Roanoke natives made it clear that they had not forgotten the conflicts of the previous year. Coming across one George Howe, an English settler out by himself spearing crabs with a stick, they shot him full of sixteen arrows and fell on him with swords of wood, bludgeoning him. Meanwhile, White was busy making peace with the Croatoan tribe that dwelt on a nearby island through an intermediary named Manteo. After learning of the attack on Howe, he mustered 25 men and led them in an attack on a nearby native village as revenge for Howe and the missing fifteen colonists, but after shooting one and running off the rest, they discovered that actually the natives they had attacked were Croatoans, their allies. Apparently the Roanoke natives had already fled their village, and the Croatoans were only there gathering what had been abandoned. Manteo and the Croatoans ostensibly forgave the English their mistake, but considering the ensuing events, it’s understandable why one might doubt the veracity of their forgiveness.

As the colonists’ first voyage had taken longer than anticipated, and as it was already late August and planting season past, Governor White was obliged to leave only a little more than a month after arriving in order to provision the settlement. Imagine it. Your daughter has just borne you a beautiful granddaughter in this wild and violent land, where lately the indigenous peoples have murdered one of your own, and you must leave your family behind to sail across the world, not to return for at least three months. Indeed, White did not want to go, but the colonists insisted as one, and he left with two vessels, leaving another behind. One can imagine him waving tearfully from the decks of his ship, shouting his promises to return forthwith.

Alas, such promises would have been made for naught, as White’s return journey encountered obstacles.

War with Spain had become official, and the crown desired that all ships be made available for naval warfare, for the Spanish Armada was extensive and formidable. Eventually, the queen allowed for two small ships to be dispatched to relieve the colonists, but in 1588, when sailing under the authority of the crown, captains of even smaller ships apparently could not resist the siren call of the sweet trade, and therefore engaged in piracy, or privateering as it was called when sailing under the auspices of a king or queen. The ship carrying Governor White seemed in no hurry to get him back to his family, for its captain set about preying on vulnerable ships throughout European waters, and eventually his ship fell prey itself, suffering a cannon volley and being boarded by the French. Reportedly brutal fighting took place upon her decks, and Governor White was lucky to have survived. Eventually, the ship returned to England, as did the other ship dispatched to bring the colonists aid.

The Anglo-Spanish War raged on throughout that year, and indeed the Spanish, at one point in 1588, reconnoitered the island of Roanoke and saw the British fort and settlement, seemingly still intact and inhabited. They planned to return and attack the colony but, as far as Spanish historical records show, never actually did so.

Meanwhile, back in Britain, White struggled to put a new fleet together. Even after the war was officially won, merchant ships were held in port against Spanish attack. Not until 1590 did White manage to get permission for a merchant privateer to carry him back to the colony, and even then the merchantman who owned the fleet refused to take any other passengers or even any supplies, as his chief interest was the taking of ships and cargo as prizes while abroad.

It had, however, been two and a half years since White had seen his daughter or granddaughter, and it is therefore understandable why he would take any opportunity to reach them, even if it meant returning alone and empty-handed. After crossing the Atlantic, the merchant fleet spent months in the Caribbean, privateering, and one can only imagine the impatience and frustration White must have felt: the longest leg of his journey complete and once again back in the New World, and they tarried south of Florida, occupying themselves with their depredations.

Finally, almost five months after leaving England, they reached Virginia and the island of Roanoke. The waters they had to cross in boats were tumultuous, and one of the fleet’s captains drowned with six other men when their boat overturned. White and others in two boats approached at night, saw a distant light and rowed toward it, blowing a trumpet and singing in English to announce their arrival in the darkness. They heard no reply. In the morning, they found that the light they’d seen had actually been a number of trees that had mysteriously been set on fire. They crossed through the burning forest and followed the beach to the settlement White had left in 1587, and as they crested a hill to approach the colony, they found a tree the letters “CRO” carved into it. On to the settlement then, and they found a palisade of tree trunks that had been placed as posts to form a wall around the dwellings, a fortification against some danger, but the dwelling places themselves, within the walls had been dismantled, and there was no sign of the settlers. One can imagine White calling out, shouting for Eleanor and Ananias, for little Virginia Dare, and receiving no answer.

They searched the settlement. Finding no one, White sought out some chests that he had buried 3 years earlier and found them exhumed, ransacked, their contents, including his maps and artwork, spread over the ground. Continuing his search, likely in mounting desperation, he looked for some sign, an indication of what might have happened to the settlers and his family. Before White departed in 1587, arrangements had been made for the colonists to leave a sign if they decided to or were in some wise forced to move inland: a Maltese cross was to be carved somewhere as a message. Eventually, a clue was discovered. On a post in the palisade, the word CROATOAN had been carved, but no Maltese cross.

To White, this was a glimmer of hope, for Croatoan was the ancestral island home of Chief Manteo, whose people had been a friend to his settlers, even despite the colonists’ accidental attack on them. Indeed, the merchant fleet had landed at Croatoan Island briefly before continuing on to Roanoke, so White, probably desperate for some hope, insisted they go back. That was when the overcast sky opened to drop a deluge of rain and wind upon them, and they fled back to their fleet. The weather did not let up, and their food and water dwindled. The merchant captains whose fleet carried White insisted they return to the West Indies for provisions before returning to search Croatoan. In the end, however, after being blown off course to the Azores, they simply returned across the Atlantic to Europe. John White was never able to organize another expedition to search for the colonists, and so he went to his grave wondering what ever became of his daughter Eleanor, his son-in-law Ananias, and his granddaughter, Virginia Dare. No seventeenth-century expedition ever turned up sign of the missing settlers. Thus the Lost Colony of Roanoke and the fate of Virginia Dare became a great mystery of the New World, spawning many a legend.

Virginia Dare’s myth only grew with time. In 1840, a novel by Cornelia Tuthill had her marrying a Jamestown colonist, an 1892 novel by E.A.B Shackelford had her keeping company with Pocahontas, and an epic poem of 1907 had her magically transformed by a Native American shaman into a white doe. Further literary treatments of her in 1908 and 1930 connected her again to Pocahontas, one presenting Dare as Pocahontas’s mother and another suggesting she was Pocahontas’s rival for John Smith’s affections. And so on, through the years, Virginia Dare has survived, never long gone from the pages of literature and popular fictions.

As to the scenarios associating her with Pocahontas, they are undoubtedly fanciful, but there is good reason to imagine such encounters, as according to at least one extant account of his adventures, John Smith, erstwhile inamorato of Pocahontas and governor of Jamestown colony, reportedly heard from Pocahontas’s father, Chief Powhatan, of the Roanoke colonists’ massacre—this an allegedly firsthand account, as the chief claimed to have been present and even supposedly showed Smith evidence: a musket barrel, a mortar and some ironwork. This tale derives from a note apparently added to surviving accounts by compiler Samuel Purchas in his 1625 Purchas his Pilgrimage, which also clearly reported that Smith sought to uncover the fate of those left behind at Sir Walter Raleigh’s colony and “could learne nothing of them but that they were dead.” Regardless of this report, however, historians remained uncertain, for although the bulk of our received history may be composed of such unconfirmed rumors as these, unreliable firsthand accounts transmitted ear to ear before being compiled for posterity, nevertheless they remain dubious. So this mystery, this blind spot in history, endures.

Detail of John Smith's map of Virginia (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Historians in subsequent eras of course developed their own theories, some involving massacre and others involving passage inland and integration into native tribes, but none could be certain. One of the most intriguing and probable theories remains that the colonists did indeed flee to Croatoan Island, now called Hatteras Island, where the friendly people of chief Manteo accepted them and integrated them into the tribe. Indeed, at the dawn of the 18th century, English explorer John Lawson wrote of a tribe he called the Hatteras that had once lived on those islands and had settled in the eastern reaches of mainland North Carolina. These natives he described as having fair skin and gray eyes; they claimed to have white forebears and appeared to be familiar with such European customs as writing and reading, or making paper speak, as they expressed it. In fact, this tribe appears to have held as tradition that they were the descendants of the Lost Colony, and in 1880, referring to themselves as Croatans, they claimed as much in their petition to the U.S. government for aid. Moreover, the Ethnological Bureau appears to have given weight to their claims, and one Hamilton McMillan, investigating for himself, found that the Croatans wore beards, had English surnames and, incredibly, spoke a pure form of old Anglo-Saxon!

Recent archaeology even appears to support the notion that the colonists were perhaps not massacred, at least not entirely, and instead assimilated with extant Native tribes. In the late 1990s, excavators began digging up English artifacts alongside native artifacts on Hatteras Island, near Cape Creek, such as a signet ring, a slate with English lettering still on it, and various other items showing evidence of metallurgy on the island. Then, in 2012, a map of the area belonging to Governor John White—perhaps one of the very maps he’d recovered from his ransacked chests—was discovered to have a diamond-shaped symbol hidden beneath a patch that may have represented the location of a planned fort.

Remember that one possible plan was for the colonists to abandon Roanoke and head inland if they were attacked and to leave a Maltese cross as a sign. Although no sign of a Maltese cross had been found at Roanoke, it might still be reasonably thought that the site marked on the map, on Albemarle Sound, could be a likely location to search for clues, and a team that had been digging up Native American pottery in that vicinity since 2006 in fact uncovered a dozen artifacts of apparently English provenance.

Now the matter is not entirely settled, of course, as historical fact rarely is, but this preponderance of evidence would appear to indicate that members of the Lost Colony of Roanoke, including perhaps the Dares, survived and lived among the Native American tribes of eastern North Carolina.

There was, however, a remarkable series of finds in the first half of the 20th century that presented a somewhat different account of events, depicting, in fact, a fantastical historical romance that boggled the imagination. And these artifacts continue even today to muddy the waters. Join us next time as we further unfold the saga of the Lost Colony and the Dare Stones….

*

Thanks for reading Historical Blindness. This installment was researched, written and designed by me, Nathaniel Lloyd. If you enjoyed this blog post and would like to read more thought-provoking stories from our shared past, please spread the word by leaving a positive review for our podcast on iTunes, Google Play Music and Stitcher and by sharing the post with any friends you think might enjoy it. Explore the website at historicalblindness.com to dig find other products, such as links to my forthcoming novel, Manuscript Found! At the bottom of the page, you’ll find links to stay up-to-date with our latest installments, products and recommendations by subscribing to our RSS feed or following us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. If you feel moved to support our program and make it possible for us to release installments more frequently, you’ll also find a page at historicalblindness.com/donate where you can contribute a one-time donation or pledge recurring support through Patreon. All donations contribute directly to the composition and production of the blog and podcast, and with enough reader and listener support, a more frequent release schedule would be more feasible. Keep an eye out for part two of The Lost Colony and the Dare Stones, which is already in the works! And thanks again for reading!

![John White's map, 1585 (source: National Geographic [my labels])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d0686e6b8f5b98e0543620/1482275146259-IN6LRRWAM85SAKILZNTM/image-asset.jpeg)