Blind Spot: The Lady of the Haystack

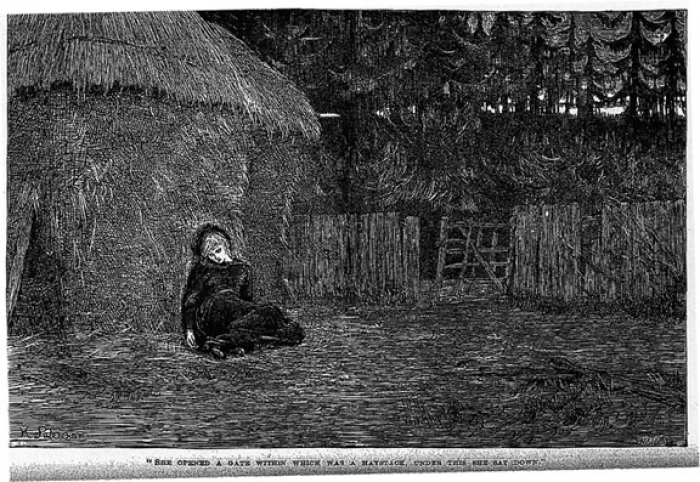

In a little village called Bourton outside Bristol, a beautiful but troubled woman appeared in 1776. By all accounts young, elegant, shapely and graceful, she enchanted those whom she encountered, who worried for her on account of the destitute condition she appeared to be in. Nevertheless, she never complained about her situation or begged for any charity beyond a drink of milk. Indeed, although everyone she encountered entreated her to come indoors and accept shelter in their homes, and especially the village women who warned her how unsafe it was for a woman alone to sleep out of doors, this unusual creature refused all their offers, choosing instead to slumber beneath the makeshift shelter of haystacks in the fields of Bourton, for as she said, “trouble and misery dwelt in houses, and that there was no happiness but in liberty and fresh air.”

Never did she share her true name with the townsfolk, who assumed from her bearing and mien that she was of high birth. In the absence of a name, he was given one: Louisa. Throughout her time in Bourton, many attempts were made to ascertain who Louisa was and whence she came. She spoke English, but with some peculiarities in pronunciation and sentence structure, such that most believed she was foreign born. One gentleman spoke to her in a variety of European tongues, most of which appeared to make her uncomfortable, and when he spoke German, she turned away, overcome with emotion and sobbing.

Walking to and fro, she showed kindness to children and accepted gifts of milk and tea and simple foods but refused the extravagances of fine clothing and jewelry, which she discarded atop bushes as though they were things of little interest or beneath her. Thus she abided in Bourton for four years, making her home among the haystacks the entire time, except for a short stay in St. Peter’s hospital in Bristol, where she was treated for insanity and promptly released. Age, illness and exposure to the elements took a toll on her beauty, but nevertheless she remained an enchanting woman. Fond of her and concerned for her well-being, the people of Bourton placed her under one Mr. Henderson’s care, in his private insane asylum in Gloucestershire. Although she had not wished to go, her health did appear to improve there. Her lucidity, however, appeared to wane, and she descended into some form of cognitive impairment, called in that era not derangement or dementia but rather “idiotism.”

Depiction of a similar scene, via The Natural Navigator

While her wits deteriorated, those who cared for her refused to give up on finding where she had come from and perhaps reuniting her with family. Based on her reaction to spoken German, they believed her to be of German origin. Therefore, as she languished in Henderson’s Gloucesterhire madhouse, her friends composed a narrative relating all they knew about her appearance in England and her behavior there, and this they published in the newspapers of a variety of major German and French cities. To their disappointment, nothing came of the narrative’s publication, at least not at first. Some years later though, as Louisa, the Lady of the Hay-Stack, continued to deteriorate in her room at the madhouse, a fantastic pamphlet purporting to reveal the secret of her origins was published anonymously in France. This mysterious pamphlet was titled The Stranger, a true history, and it began with an introduction of sorts that gave the particulars of Louisa’s previously published narrative before tantalizingly suggesting that this poor Lady of the Hay-Stack might indeed be one and the same as the subject of the narrative it went on to share.

The pamphlet began its story in 1768, when one Count Cobenzl, minister plenipotentiary of the Austrian Netherlands under Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, received a cryptic letter from a woman at Bourdeaux calling herself Mademoiselle La Frülen. In this letter, she said that she had written to him because of how universally respected he was. She was soliciting some undefined aid from him, and she assured him that when he knew who she was, he would likely be glad to have helped her. Cobenzl then received another letter signed by a Count Weissendorf from Prague suggesting that Cobenzl do all he can to help this La Frülen woman, and to advance her money if she desired it, for again, “when you shall know, Sir, who this stranger is, you will be delighted to think you have served her, and grateful to those who have given you an opportunity of doing it.” And then another similar letter from one Count Dietrichstein of Vienna arrived, entreating Cobenzl again to help this stranger with a false name.

Cobenzl replied to La Frülen that he’d be happy to help her but must be told her real name. Their correspondence continued, and as she prevaricated, Cobenzl was visited by a woman from Bourdeaux who knew the mysterious letter writer, speaking very highly of her and sharing with Cobenzl that, due to her mysterious origins and the fact of her remarkable resemblance to the late Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, founder of the Habsburg –Lorraine dynasty, many rumors had arisen about her extraction. Meanwhile, La Frülen assured Cobenzl that she would tell him everything, but for the time being she sent him a portrait of herself, saying that it might give some hint as to what she would tell him. The subject of this portrait appeared to bear a remarkable resemblance to the late emperor, and this judgment was made by none other than the late emperor’s own brother, Prince Charles of Lorraine, whom Count Cobenzl had shown the painting.

Portrait of Count Cobenzl, via Wikimedia Commons

As Cobenzl continued to exchange letters with this stranger, she sent him further portraits, this time of the empress and the late emperor, suggesting Cobenzl compare her portrait only to the latter. The implication was quite clear, and Cobenzl felt he had to tread rather carefully, yet he continued to receive letters from elsewhere commending him for helping this Mademoiselle La Frülen and beseeching him to keep her secret. After about half a year of this, though, in the early months of 1769, he received letters of a different sort. These communications from Vienna indicated that the authorities were in the process of arresting this La Frülen in Bourdeaux and shipping her to Brussels to be questioned by Count Cobenzl himself. For it appeared that the King of Spain had also received a letter about this woman in Bourdeaux, this missive purporting to be from Emperor Joseph II himself claiming the girl as his half-sister and the natural born daughter of the late Francis I, but when the King of Spain contacted His Imperial Majesty about this letter, the Emperor denied writing it, informed his mother, the Empress, that a forger and impostor in Bourdeaux was seeking to pass herself off as a Habsburg-Lorraine and forthwith dispatched legal authorities to apprehend her!

Upon arriving at Brussels and being conducted to Count Cobenzl, the mysterious Mademoiselle La Frülen charmed everyone with her beauty and bearing, and surprised some with her striking resemblance to the late emperor. She appeared to be under the impression that her arrest was due to debts she had incurred in Bourdeaux, which had been her reason for writing to Cobenzl for aid in the first place. The tale this woman shared with Cobenzl and her other interrogators was a sad one indeed. She had no notion of her birthplace, but believed she had been raised in Bohemia, where she remembered a remote country house and two kind women who nurtured her, and a man of the cloth who occasionally visited to say mass and catechize her. The women took it upon themselves to teach her to read and write, but this priest, upon discovering the fact, forbade it.

Thus she persisted, a chaste and pious youth sequestered from all society, until a man she did not know came to visit her wearing a hunting-suit, put her on his knee and remarked upon how grown she was. Lovingly, he encouraged her to behave well and obey her guardians, and he took his leave. He made a great impression on her, and when he returned more than a year later, dressed again as though out on a hunt, she committed his features to memory, such that she could and did describe him in detail to Count Cobenzl and her other interrogators. At the conclusion of the man’s second visit, she wept, and he appeared moved, promising to visit again soon. However, he did not return for two years, explaining then that he had intended to visit sooner but had taken ill. During this third encounter, the youthful Mademoiselle La Frülen expressed her familial love for the man, and he likewise expressed love for her, promising to see to all her needs and provide her an opulent life of wealth. He then gave her three portraits, one she recognized as being of himself, which he admitted, and one of a regal-looking woman. These, she claimed, were the portraits of the late Emperor Francis I and Empress Maria Theresa that she had sent to Count Cobenzl. The third portrait depicted a veiled woman, which the man claimed was her mother. Along with the portraits, he gave a gift of money and a promise to soon fulfill all her grandest wishes, but he also made her vow never to marry.

Portrait of Emperor Francis I, via Wikimedia Commons

The implications of the tale were clear. If the man had been the same as the subject of the portrait given to Cobenzl, that made him Emperor Francis, and some other particulars of the tale indicated that she was supposed to have been his daughter. For example, in explaining to her some article of his clothing as an officer’s distinction and then endeavoring to explain what an officer was, he indicated that they were honorable and gallant men whom she should love, being herself the daughter of an officer. And later, when asking her whether she would like to meet the Empress, he said, “You would love her much if you knew her, but that for her peace of mind, you must never do,” implying some secret kept from the Empress. Thus the fact he always visited in hunting clothes, for what better excuse to make a visit to the countryside than a hunt. And La Frülen’s descriptions of his features, and in particular a distinguishing pale mark on one of his temples, seemed to fit the late Emperor Francis exactly. In fact, the detail that he had become ill during a specific period was corroborated by the late Emperor’s brother Charles, who recalled Francis becoming ill after returning from a hunting trip around that time.

Eventually, the priest who taught her catechism informed her that the kind visitor she so loved had passed away and had left instructions that she be taken to a convent. So terrified was she of life in a convent that she fled from her chaperones during the journey, ending up sleeping in a barn. Thereafter, relying on the charity of those she encountered, she was able to find passage to Sweden on a carriage but fell from the conveyance during the journey, suffering a grievous head wound and having to stay with a Dutch family at their inn until her recovery. Thereafter continuing to Stockholm, she encountered the first of a series of charitable noblemen who, on account of her resemblance to the late Emperor and based on cryptic recommendations to offer her aid, took her in, provided her with gifts and loans and generally saw to her every need and comfort. Everywhere she went in those years, from Stockholm to Hamburg to Bourdaeux, she fell in with an aristocratic element, who often received letters from afar entreating them to offer her succor and charity, hinting at the tantalizing secret of her lineage.

Such letters, of course, Count Cobenzl and his fellow interrogators were well familiar with, and they informed Mademoiselle La Frülen that she was not in custody because of the many debts she had accumulated in Bourdeaux but rather for the forging of letters and for fraudulently posing as the daughter of Emperor Francis. In great distress, she admitted to having forged the letter from Emperor Joseph II to the King of Spain as well as some other letters, but she justified this based on the threats she had received from creditors and refused to recant the story of her youth and its implications that she was a natural born daughter of the Emperor. As for many of the other letters, some of which Count Cobenzl himself had received recommending him to offer her aid, she claimed absolute ignorance of them, suggesting that her father must have instructed a great many people to see to her welfare, and that they continued to do so from afar. Moreover, she indicated that she had no desire to continue seeking charity from others but that she had no choice because of the vow she had made never to marry. Several advantageous proposals had been made to her in Bourdeaux that would have seen her well taken care of, but she had refused them to keep her promise.

Portrait of Empress Maria Theresa, via Wikimedia Commons

Having received the details of this interrogation, the Empress was disposed to treat the prisoner as severely as possible, but before any action was taken against her, Count Cobenzl became very fatally ill. While on his death bed, he received a mysterious letter that he afterward burned. Something in the content of the letter appears to have convinced him to treat Mademoiselle La Frülen far more leniently than the Empress wished, and after Cobenzl’s death, she was conducted to a small town and left there to her fate with a sum of fifty gold coins.

Thus the pamphlet ended in the year 1769, insinuating that somehow this poor woman, driven quite mad by her circumstances, found her way across the Channel seven years later to England and Bristol, to lead a sad but tranquil life among the haystacks of Bourton. In support of this speculation is the report that, among the several languages other than English spoken to her, Louisa, the Lady of the Haystack, only appeared to respond in any way to French and German. She appears to have been illiterate, never looking in a book even when one was offered to her. Some reported finding a distinct scar on her head that seemed to corroborate the story of her fall from a carriage. As her faculties had drastically diminished, all questioning of her regarding the content of the pamphlet was largely fruitless. She babbled about her mamma coming for her mostly, but once, when it was suggested that they take her to Bohemia, she is said to have replied, “That is papa’s own country.”

After a long illness, she died in Mr. Henderson’s madhouse in December of 1801, by all accounts still a happy and mirthful woman even if she had lost all of her wits. She seems to have reverted to a childlike nature during that final season of her life. And she left behind many questions to which we may never know the answers. Who was she? If she was Mademoiselle La, then was she indeed the daughter of an emperor? Or was she merely a forger and confidence woman? Just as Mademoiselle La Frülen remains a question mark blemishing Continental history, in all likelihood, Louisa, the Lady of the Haystack, will ever remain a blind spot in British history, a mystery in her own time as well as an enigma in posterity.