Stranger Things Have Happened: Psychic Spies

In a previous series, I spoke in great depth about Nazi occultism. Among many in the Third Reich, their nationalist and racial ideology was founded on a view that Germans were the descendants of lost race, and that the power of this race survived in ancient Norse runes, Teutonic magics, and legendary artifacts scattered around the world. Heinrich Himmler was the most prominent and influential of these true believers, and he started Das Ahnenerbe, the Institute for the Research and Study of Heredity, to investigate and prove the veracity of his obsessions. The man he placed at the head of this organization was Karl Maria Wiligut, a medium who claimed to be in psychic contact with the lost Aryan race Himmler imagined were his forerunners. Wiligut had previously been certified insane, but Himmler believed in his abilities, and under Wiligut, Das Ahnenerbe delved into more and more arcane areas of study, beyond the archaeological expeditions to prove their theorized heritage or the pseudoscientific conjecture about weird cosmological views like the Hollow Earth Theory or the World Ice Doctrine. Through the “Survey of the So-Called Occult Sciences,” they investigated spirit channeling, divining, astrology, and other forms of extra-sensory perception, or ESP. However, Adolf Hitler called all of it “nonsense” and complained about Himmler wanting to bring back the mysticism they had left behind when he had suppressed the Catholic Church. Indeed, in 1941, Hitler launched Special Action Hess to suppress the occult, arresting all known practitioners of ESP or the divining arts, be they fortune-tellers, astrologers, healers, or just anyone who claimed to be clairvoyant, and he seized all their literature and the trappings of their arts as well, including crystal balls and tarot cards. But Hitler had good reason for this outside of his distaste for their supernatural claims. The Special Action was named after Rudolph Hess, his former deputy Führer, who in May of that year had secretly flown to Scotland on an unauthorized peace mission and been captured. Hitler believed Hess had been encouraged in his plans by false horoscopes manufactured by the UK as propaganda, and this, it seems, was the real reason for the suppression of the occult in Special Action Hess. While the Nazis were earnestly studying divination and anomalous mental phenomena, British intelligence was making use of such practices in more devious ways. It is unclear whether Hess really was influenced by fabricated horoscopes, but it is known that British intelligence, aware of how many Germans trusted in astrology, did forge horoscopes as propaganda. In fact, they engaged the services of a woman famous for claiming to be a “witch,” Sybil Leek, to write these bogus horoscopes. Likewise, the most famous astrologer in America, Louis de Wohl, whose popular syndicated column, called “Stars Foretell,” usually focused on the war in Europe, was unbeknownst to his U.S. readers actually a propagandist for British intelligence, fabricating reports for the sole purpose of convincing Americans that the U.S. should enter the war. In the aftermath of the war, as U.S. intelligence competed with the Soviets to seize Nazi science, it was discovered that Das Ahnenerbe was taking ESP seriously, and much as the race for mind control began, this marked the very start of what would become a Cold War psychic arms race.

If you haven’t read part one of this series, check it out before reading on. It’s not a single story, and you can enjoy this installment alone, but you should know that this series is an exploration of the historical and pseudohistorical basis of the popular Netflix series Stranger Things. As you may or may not know, the premise of that show involves a psychic character whose powers were studied and cultivated by a secret U.S. government experimentation program. In part one of this series, I discussed the very real human experimentation programs conducted by the CIA under the cryptonym MK-Ultra in search of mind control technology, and in this episode, we will look at government sponsored programs studying extra-sensory perception and psychokinesis. These categories of phenomena cover most of the capabilities of the psychic character in Stranger Things, who demonstrates the ability to move objects with her mind, see others’ thoughts or memories, and even spy on someone over a great distance as though through out-of-body experience, a technique that has come to be called “remote viewing.” Just as all of the dastardly human experiments undertaken by MK-Ultra were absolutely true, so too are the U.S. government studies and experiments with ESP. However, whereas Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA eventually came to accept that the elusive mind control drugs or techniques they sought did not actually exist, many of the scientists involved with ESP programs were true believers. What we must consider in this installment of the series is not just what happened, but also whether what happened was genuine anomalous mental phenomena or can be more rationally explained. Among the first government-sponsored ESP experiments organized after World War II were those in 1952, when the Department of Defense tasked J.B. Rhine with studying the psychic powers of animals. Rhine had coined the term ESP back in the 1920s and conducted some of the first experiments to study it in his Parapsychology Lab at Duke University. For the DoD, he conducted tests to determine whether dogs could psychically discern the location of landmines, whether cats could telepathically follow instructions to choose one food dish over another, and how homing pigeons made their way home. His experiments with dogs and cats yielded no results that couldn’t be explained by chance, and as for the abilities of homing pigeons, those remain a mystery today. After these failed experiments, the U.S. government’s interest in ESP resumed, perhaps unsurprisingly, when it coincided with its search for a viable mind control drug.

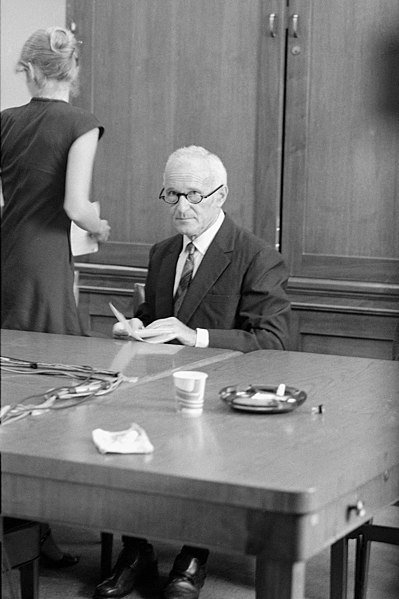

J.B. Rhine, Father of Parapsychology, testing subjects’ ESP abilities with Zener cards. Via NCDR.gov

Under the umbrella of MK-Ultra, Subproject 58, headed by Morse Allen, involved the search for the legendary “magic mushroom,” a fabled Mexican drug that it was thought could be useful, if not as a mind control agent then perhaps as a poison. The problem was that the “magic mushroom,” or teonanáctl, the “god’s flesh” mushroom, had never been proven to really exist. In his search for it, Morse Allen had sent a chemist to masquerade as a botany professor and infiltrate various mycology enthusiast groups, with little luck. Eventually, a man who had reportedly traveled to Mexico and been in contact with shamans who used the mushroom in their rituals came to their attention. They learned of him through a third party, Andrija Puharich, a towering figure in the study of ESP. Puharich had been fascinated with the topic since he was a child and believed he had calmed an aggressive dog with only the power of his mind. After serving in the armed forces, he earned a medical degree and published numerous papers theorizing that some unknown energy force connected to the brain and nervous system might explain anomalous mental phenomena. Dashing and charismatic, Puharich seemed to attract wealthy benefactors who gladly bankrolled his research projects, allowing him to start the Round Table Foundation, dedicated to experimentation that might take the topic of ESP out of the realm of parapsychology and into the realm of science proper. Among the admirable work that Puharich undertook was the study of human hearing, which he suspected may overlap with or provide insight into ESP. During the course of his foundation’s study of the topic, a revolutionary surgery to restore hearing was discovered by one of the doctors on his staff. Furthermore, during his study of psych ward patients who hear voices, it was he who discovered that a man’s dental fillings can actually receive the broadcast of nearby radio stations and thereby saved some otherwise mentally healthy individuals from unnecessary institutionalization. Puharich left his Foundation for a time to work for the government. Having delivered a speech to the Office of the Chief of Psychological Warfare, the Army thought ESP might just be a worthwhile field of inquiry and called him back into service, stationing him at the Army Chemical Center in Edgewood, Maryland, and tasking him with finding “a drug that might enhance ESP.”

It was, of course, during his search for ESP-enhancing drugs for the Army that Puharich first took interest in the “god’s flesh” mushroom, which legend had it provided divinatory powers to the shamans who consumed them during rituals. However, when Puharich tracked down the explorer who had found the Mexican mushroom-eating shamans and brought him to the CIA’s attention, hoping to get security clearance and join MK-Ultra Subproject 58, there was a problem. Puharich was viewed as something of a crank, and for good reason. He had a habit of giving in to his confirmation bias and falling for the acts of stage mystics and charlatans, becoming obsessed with each new psychic he studied. In fact, his interest in the “magic mushroom” had only been stirred because a spirit channeler named Harry Stump had claimed while in a trance that it “would stimulate one’s psychic faculties,” and Puharich took this as gospel truth. In the end, Morse Allen chose not to grant Puharich security clearance and instead circumvented him, approaching the explorer, a man named R. Gordon Wasson, who happened to also be the vice-president of J.P. Morgan bank, directly. Financing his further expeditions, the CIA was then in on the ground floor when Wasson became the first white man in history to partake of the drug and returned to America with enough of the mushroom that the CIA could grow more. Once again, as with LSD, the CIA was responsible for the entrance of psychedelic mushrooms into our culture, and though Puharich had been cut out entirely, Wasson still gifted him a supply of the drug. Leaving the Army, Puharich returned to his Foundation and began further experiments, locking up the supposed psychics who obsessed him, like Harry Stump, in Faraday cages as a laboratory control and feeding them mushrooms. Gradually, Puharich’s personal life and his experiments would drift out of control, until both his marriage and his Foundation failed, but he always found a way to stay afloat. He sold his services as an expert in mushroom toxicology to the Army and later won funding from various other government entities, like the Atomic Energy Commission and NASA, for further ESP experimentation programs throughout the 1960s, all the while investigating a variety of purported psychics. In the 1970s, his study of one such individual, Uri Geller, would eventually bring the CIA around to working with him after all. As the Cold War had dragged on, it was feared that the Soviets had themselves a psychic super soldier. Therefore, we would need one ourselves, or at least we would need to seem like we had one.

Andrija Puharich, perhaps the most prolific tester of psychic phenomena on behalf of the U.S. government.

The CIA had good reason to fear Soviet progress in psi research, but they also had good reason to doubt it. The reason for this dichotomy was that intelligence reports had revealed the ESP and psychokinesis studies the Soviets were conducting, but there was always the strong possibility, especially in so fantastical a field, that what they’d learned was actually disinformation intended to mislead the U.S. about their capabilities. Certainly it was true that the Soviets were conducting psi experiments, and they had taken care to do so under euphemistic names, trying to present such research as strictly scientific since any mysticism or religion was anathema to good Marxists. So their research facilities were given pseudoscientific names like the Special Laboratory for Biocommunications Phenomena, and the topics of their research were equally coded. Psychokinesis, or PK, what we might call telekinesis today, was referred to as “emissions from humans,” which if I were a little less mature I might make a crude joke about. Likewise, telepathy was called “long-distance biological signal transmission.” But what troubled U.S. intelligence more than these was what they called “psychotronic weapons.” Intelligence suggested that the Soviets’ investigations in the area of so-called biocommunications were two-pronged; they studied individuals who claimed to be capable of the phenomena, but they also developed weapons meant to neutralize the capabilities of such persons, which meant devices that generated “high-penetrating emission(s),” typically microwave or electromagnetic, intended to interfere with brain function. Indeed, it was discovered in 1962 that such emissions were being actively transmitted toward the upper floors of the U.S. embassy in Moscow, which realization sent U.S. intelligence scrambling to study the technology themselves. Though their research could not definitively prove that the emissions were having a harmful effect on embassy staff, certainly the presence of the microwave radiation disrupted U.S. intelligence operations and had them chasing their tails for a while, secretly testing the health of everyone in the building. There are other theories and considerations with the Moscow Signal, of which I’ll have more to say in a patron exclusive, but perhaps that was the point of it, just to mess with their heads in a psychological sense. Such an objective could also be ascribed to the most terrifying of supposed Soviet breakthroughs in psi: the experiments conducted on Ninel Kulagina. This woman, a former Soviet soldier, was purported to be gifted with astounding psychokinetic abilities. The West knew this because state-run Soviet television had produced a special documentary about her, showing her moving small items like matches and salt shakers with her mind. Think of the scenes in Stranger Things when the psychic character sits staring at a Coke can, trying to crush it with her thoughts. But U.S. intelligence had acquired supposedly classified footage of Kulagina supposedly stopping a frog’s heart with her mind, which raised the possibility of a psychic assassin being able to perpetrate untraceable murders. Of course the American intelligence community recognized that it might all be fake, that the feats shown in the footage were a clever fraud, and that the TV program as well as the classified film in their possession was just propaganda. Just the same, it seemed the U.S. was in the market for our own psychics capable of telekinesis, or at least some people we could suggest were capable of it to the world and specifically to our Communist rivals.

The candidate that Puharich brought to the CIA’s attention was an Israeli man named Uri Geller who had made quite a name for himself. He performed in theaters like a stage magician, but he claimed his powers were real, not illusion. Not only did he perform feats of supposed mental telepathy, but he also bent spoons with only the power of his mind, or so it seemed. Unsurprisingly, Puharich took an interest and brought him to America for testing, and when he called up the CIA to say he had a genuine telepath capable of psychokinesis, the agency was so pressured by rumors of Soviet psychic soldiers that they took Puharich up on his suggestion of funding his research with Geller. However, the CIA still thought Puharich a liability, and furthermore, there were rumors that Geller was with Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency. If American and Soviet intelligence were in the business of finding or pretending to find psychic assets, then it followed that Mossad may have been following suit. Furthermore, the feat that brought Geller great international fame was when he appeared to predict that Gamal Abdel Nasser, the President of Egypt, had been killed, information that might have been advanced to him by his handlers to bolster his claims. The CIA therefore insisted that an agent of their own, Kit Green, oversee the study of Geller, and to distance themselves from association with Puharich and his foundation, they directed their funds to the Mind Institute of Los Angeles, an organization created by Edgar Mitchell, a former astronaut interested in the research of psychic phenomena whom they insisted be involved. Despite what seem to have been precautions taken to avoid exposure in the press, Uri Geller’s celebrity in America and the UK continuously rose, such that it was compared to Beatlemania. Considering the kinds of mystifying feats he performed and how much of a household name he was, I would compare him more to David Blaine today. The height of his fame came when he went on BBC Radio and urged all of the UK to concentrate with him at the same time, willing a spoon to bend, and the BBC’s switchboard was inundated with calls from listeners claiming to have bent spoons and other items in their own homes. Of course, these reports were never confirmed, nor could they be, really. But aside from the obvious doubts about Uri Geller’s abilities, which we will discuss next, there is the burning question of why the CIA, who were conducting classified research into his abilities, would allow him to parade them around the world on a press tour. On paper, Puharich was blamed for this breach of secrecy, but one cannot help but wonder if this is exactly what the CIA wanted: well-publicized reports that they too had in their employ psychics whose powers might rival those of the mysterious Ninel Kulagina.

Ninel Kulagina, moving a compass in what is certainly a Soviet propaganda film probably faked using magnets under the table.

With Geller’s fame arrived accusations of fraud. But these were not lobbed just by sardonic journalists in the usual skeptical editorials. Geller’s outrageous claims of possessing supernatural powers and his unprecedented celebrity were enough to galvanize the scientific community. Astronomer Carl Sagan, mathematician Martin Gardner, and psychologist Ray Hyman came together with magician James Randi, who insisted Geller was an illusionist rather than a genuine psychic, and formed the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, a noted skeptic organization that is still active today, for the sole purpose of combatting the surge in irrational belief they were observing. Most criticism of Geller comes down to his act being a pretty typical stage magician’s act, using distraction to pre-bend spoons and then hold them in such a way as to dramatically reveal the bend, making it look as if it is only then being bent. Indeed, there have been times when Geller refused to even perform if magicians were present, likely because he knew they would see through his tricks. As for his telepathic demonstrations, he has even admitted that his manager, a young man named Shipi Shtrang, helped him to fake certain psychic feats like guessing audience members’ license plate numbers. As for secondary effects, such as the people who claimed Geller had somehow imparted to them the ability to bend spoons themselves, a simple explanation is that mass delusions can be encouraged by the power of suggestion, and that believing a thing to be true can have concrete effects that may seem to confirm its truth, a phenomenon related to the concept of a self-fulfilling prophecy or the Tinkerbell effect, a sociological concept called the Thomas theorem, which states that “if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” But regardless of skeptical opposition, the CIA continued their experiments with Geller. According to later declassified reports, Geller was the subject of experimentation by nuclear scientists working at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who tested his ability to affect the computer program cards inside an ICBM, exploring the proposition that a person with psychokinetic abilities could feasibly deactivate nuclear missiles in flight. Strangely, after these experiments, the scientists involved experienced weird poltergeist activity at home, seeing unexplained phenomena like floating images and orbs. It was so bizarre that Kit Green, the CIA agent overseeing the experiments, reportedly came to believe that they had become the focus of a CIA psychological operation, using drones and holograms—the fact that a CIA man, and one who himself said he ran the ”weird desk,” would think this the likeliest explanation of such paranormal phenomena goes a long way toward supporting some of the theories about UFO disinformation programs that I discussed in previous episodes. Aside from this, though, it’s hard to know what to make of this bizarre report. What is more curious, to me, is the fact that the results of one of the Geller experiments was declassified in 1979, revealing that a magnetic program card had seemingly been erased when Geller was concentrating on it. If the result of this experiment is to be trusted, why would U.S. intelligence declassify it? It occurs to me that, if this were a genuine breakthrough in the use of psychic powers as nuclear self-defense, we would want to keep it secret at all costs. However, if it were not genuine, but we wanted our enemies to believe we were developing such capabilities, only then would we want it declassified. Framed in this manner, it makes one wonder how much of U.S. intelligence’s psychic experimentation programs that have remained classified were purposely falsified and leaked as disinformation, just as it was suspected that the footage of Ninel Kulagina had been.

Uri Geller was not the only psychic asset being studied by the CIA in the 1970s. Another man, studied at the same facility where Geller was often studied, the Stanford Research Institute, or SRI, was Ingo Swann, who formerly acted as a psychic test subject for the oldest psychic research organization in America, the American Society for Psychical Research. During his time with the ASPR, he began to undergo experiments involving the projection of his consciousness outside of his body, called travelling clairvoyance. These experiments involved suspending a tray in the air across the room and asking him what was on it. These experiments drew the interest of a physicist named Hal Puthoff, who invited Swann to SRI, a laboratory affiliated with the Defense Department, and reportedly tested him by directing him to agitate a magnetometer located several feet below him, encased in concrete. The story differs according to the telling, with Puthoff and Swann describing a perturbation of the device’s readings as having never been seen before or since, representing it as a successful demonstration of Swann’s psychokinesis, while other scientists have suggested it was a relatively common frequency variation for which Swann merely took credit, or that the machine had malfunctioned coincidentally and remained out of order afterward. One thing is certain, though; they never repeated the experiment, which any scientist worth his salt would have done before thinking to tout it as evidence of anything. During his time at SRI, Swann adapted his travelling clairvoyance routine and renamed the feat “remote viewing,” a name that Hal Puthoff and another physicist at SRI, Russel Targ, preferred because it sounded far more scientific. At first, their remote viewing experiments involved an individual going somewhere and concentrating on what they saw while Swann sat in a Faraday cage and tried to sketch what he thought the individual was looking at. However, since they were working for the CIA and clearly developing techniques for espionage, even if they weren’t openly acknowledging it, it became apparent that, even if this process produced results, it was pretty pointless, since if they were sending an operative into the field to infiltrate some site, they wouldn’t need the remote viewer at all. Rather, to be useful, Swann discerned that a psychic would need to be able to remote view any location, without a person present at the site sending back willful thoughts about the place. He came up with the idea that they would use coordinates. Kit Green asked an acquaintance for a set of coordinates, not knowing what was at the location, and Swann sketched the place. The results were rather vague, and at first didn’t seem to match the location Green’s acquaintance had provided: a family cabin. However, when another individual volunteered his remote viewing services, the details were far more precise, and it appeared the remote viewers were focused not on the cabin but rather on a top secret military facility called Sugar Grove just nearby the cabin.

Uri Geller, celebrity psychic, displaying a spoon he claims to have bent with his mind. Notice the film does not show the spoon bending. Gif uploaded by MindBob on Tenor.

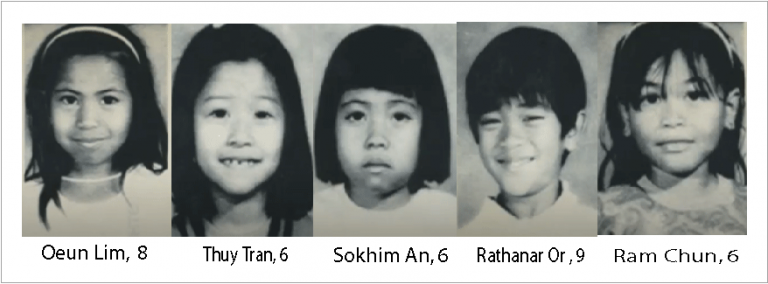

This other, more accurate remote viewer was a Scientologist named Pat Price, and he presented himself to the researchers at SRI in a very strange way. He just approached them while they were out buying a Christmas tree for their lab and said he could help. Later, when Ingo Swann was in the process of attempting to remote view the coordinates provided by Kit Green, Price just called up Puthoff and offered his services. Curious, Puthoff gave him the coordinates, and a couple days later, Price called him back with an astonishingly detailed account. When it was discovered that the two men, Swann and Price, seemed to be viewing the Sugar Grove facility, Price’s reading raised alarms. Apparently, it was so precise that it described the color of filing cabinets and the names that appeared on the files therein. Even the rather credulous Hal Puthoff could hardly believe it and came to suspect Price was a CIA plant, ordered to approach them and test whether they could detect a fake who might have been feeding them sensitive intelligence as if it were psychic impressions. After all, Geller was still suspected of being Mossad, so the CIA had reason to fear they might be fooled. Very quickly, though, the interest of the agency shifted from Ingo Swann to Pat Price. Swann left SRI, perhaps a little resentful, and Price left to work directly for the CIA. This can’t necessarily be taken as evidence that he wasn’t working for them all along, however, as it’s quite possible that because of Price’s performance, the CIA decided the program at SRI was a liability, and Price left just to come back into the fold, his operation concluded. Certainly the CIA got out of the psychic research business after that, but not until after a very mysterious event. Pat Price was on a visit to Las Vegas in 1975 and met up with Kit Green and Hal Puthoff for dinner and reminiscence. At dinner, he left early, not feeling well. Afterward, he died of a heart attack in his room. An unidentified man arrived later with Price’s medical records and waived an autopsy. The researchers at SRI suspected murder, but who to suspect? The CIA themselves, or perhaps the KGB? Apparently, the Church of Scientology even came under suspicion. In the end, though, we don’t know what Price did for the CIA, or why he might have been killed, or whether he even was killed, for after all, he might have simply succumbed at 57 years old to a cardiac event.

After the CIA discontinued their funding of the psychic research at SRI, Uri Geller continued in his quasi-mystical, illusionist-esque career, fading slowly into relative obscurity and becoming something of a joke. Most recently, he threatened to telepathically prevent Brexit, and obviously failed to do so. While the CIA may have given up on remote viewing, though, the U.S. government in its entirety did not, and afterward, the Defense Intelligence Agency revived the endeavor under the codename Stargate Project. With a manual for training soldiers to remote view written by Hal Puthoff and Ingo Swann, they kept psychics on the payroll, loaning them out to whatever agency or branch of the armed forces wanted to use them, until the project was declassified in 1995. At that point, as the DIA sought to transfer the project back to the CIA, two academics, statistician Jessica Utts and psychologist Ray Hyman, one a believer and one a skeptic, were engaged to evaluate the 20-year project. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they came to opposite conclusions, but Hyman’s reservations, published in Skeptical Inquirer, show that, even 20 years later, much of the same fundamental problems with psychic research remained. The problem of inadequate laboratory controls has always been an objection of skeptics. For example, the original remote viewing activities of Ingo Swann and Pat Price, in which they described the Sugar Grove facility, were completed at home, with no supervision. They could have researched the coordinates or received outside information. Additionally, the problem of the bias of the researchers who undertake these studies, like Puharich and Puthoff, who were always entirely convinced of their subjects’ abilities, was always an issue. Just the same, in the 90’s, Hyman’s central objection was that all the remote viewing studies, which involved the evaluation of sketches to determine likenesses to the target supposedly being viewed, relied on a single judge, the person conducting the experiment, who was invariably a believer. He pointed out that even statistically significant results, which seemed to indicate something more than chance, were suspect until independent judges could reproduce the same results. And the repeatability and reproducibility of supposedly successful results in psychic research has also always been problematic, with researchers routinely claiming that results cannot be reproduced if observed by non-believers, a difficulty that should not be and is not an issue in science generally. In the years since its declassification, remote viewing became the stuff of satire, like the book and movie The Men Who Stare at Goats, and today these experiments are something of a laughing stock to many, despite the former participants in the program and practitioners publishing numerous books and speaking regularly on the paranormal circuit. But even as far-fetched as their claims are, they still pale in comparison to the final and perhaps biggest inspiration of the series Stranger Things, which was an outright hoax.

The Stanford Research Institute group, from left to right: Hal Puthoff, Russell Targ, Kit Green, and the mysterious Pat Price. Via Vice.

Until next time, remember, in science, experiments must devise positive tests to discern whether a phenomenon is present or absent, but no such tests have ever been devised for psychic powers, which are defined negatively: when normal explanations are eliminated, researchers claim that is evidence that psychic phenomena exist. But that’s not how science works. You can’t point to any fluctuation in the data of your study and claim it proves your pet paranormal phenomenon is real.

Further Reading

Hyman, Ray. “Evaluation of the Military’s Twenty-Year Program on Psychic Spying.” Skeptical Inquirer, vol. 20, no. 2, March/April 1996, pp. 21-23. Center for Inquiry, cdn.centerforinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/1996/03/22165045/p21.pdf.

Jacobsen, Annie. Phenomena: The Secret History of the U.S. Government's Investigations Into Extrasensory Perception and Psychokinesis. Little Brown, 2017.