The Trial of Levi Weeks for the Murder of Elma Sands

On New Year’s Eve, 1799, the reports of rifles were heard across Manhattan Island every half hour, from dawn to sunset, but this was not a celebratory discharge of arms. Rather, it was a dirge, a military salute to the late revolutionary hero, George Washington, who had passed away two weeks earlier and whose funerary march filled the snowy streets with mourners that day, with dragoons at the forefront hauling captured British artillery, followed by cavalry, militia and veterans of the revolution. Thereafter came the fraternal orders of the city, like the Freemasons in their odd regalia, and the city’s major financial players, members of the boards of its influential companies, followed by city councilmen and the denizens of Columbia University before the rank and file of its general professionals in the medical and legal fields.

This spectacle was a fitting end to the year for Manhattan, for the city had been plagued by death that year. Before Washington’s death cast a final pall over the city, it had suffered many losses among its own populace from Yellow Fever, such that before the season had ended and the epidemic subsided, the island had become something of a ghost town, with many fleeing the city, and leaving its streets as dead as the fever’s victims. It was generally agreed that the source of the city’s troubles with the fever was its potable water supply, entirely provided by one pump, the Tea-Water Pump, a supply that many believed had been contaminated by the tainted waters of the nearby pond known as the Collect, which had become brackish from furnace and tannery waste as well as from dead animals and the personal effluvium of chamber pots. This was no new problem, and by the end of the century, it looked like a resolution had finally been reached, as a recently formed concern called the Manhattan Company, members of whose board marched in Washington’s memorial parade on New Year’s Eve, had developed a solution: wooden pipes had been laid to carry fresh water from Lispenard’s Meadow outside of town right to the citizens. And so life and populace had been returning to Manhattan at the close of the year when news of Washington’s passing reached them.

The Manhattan Company laying wooden pipes to bring fresh water to the city, via 6sqft

Lest it be thought that the people of Manhattan were united in their gladness at having survived the fever and their sorrow over the late General Washington’s passing, though, it should be established how very divided the city was. American politics had settled quickly and firmly into a two-party system, with the Federalists, who sought firmer central control through constitutional prerogative and a newly established national bank and federal mint, and the Democratic-Republicans, who opposed such centralization and were often characterized as radicals like unto revolutionary French Jacobins. And the poster boys of these two great factions could both be found among marchers in that sad New Year’s Eve procession: Alexander Hamilton, dyed in wool Federalist and founder of the Bank of the United States, marching among the veterans of the revolution, and his former brother-in-arms and erstwhile nemesis Aaron Burr, Democratic-Republican and former Attorney General and Senator of New York, marching with the board of the Manhattan Company, the water-bringing savior of the city that Burr had founded. These two parties, and these two men, found themselves locked in a struggle for the control of not only New York politics, but also the control of national politics. The upcoming election of the presidency, after all, would be determined there in New York, as local elections in this most populous city of the nation would stack the state legislature, which itself appointed electors and thereby controlled the outcome of presidential elections. Previously, Hamilton and the Federalists held sway, wielding power over city merchants with their national bank, but Burr had recently managed something of a coup. Taking advantage of a loophole in the charter for the Manhattan Company that Hamilton himself had signed, a vague clause that allowed the company to make use of surplus funds however it saw fit, Burr had managed to create a bank under the guise of a water company and thereby loosen the Federalist stranglehold on the electorate. In fact, Burr’s use of cheap materials, choosing wooden pipes to bring water from Lispenard’s Meadow to the city, seems to indicate that the water project was only a means to an end. Although he did bring fresh water to the people of Manhattan, he appears to have been more focused on bringing political capital to his party and himself.

This was the context in which that funereal parade took place, two titans of American society among its marchers. And any who know their fair share of history are well aware that the fate of these two men was to be closely intertwined, but the day of their fateful duel was still far in their future, and long before that, these two men, lawyers both, would find themselves sitting at the same table, united in the purpose of defending a man, the question of whose guilt would see the city further divided.

A depiction of another funeral parade for Washington, in Philadelphia, via Wikimedia Commons

*

Two days after the memorial parade, the new century having begun with a sharp cold snap, a rotund man in the baggy clothes and floppy hat of a Quaker, strode resolutely out to a house on the edge of Lispenard’s Meadow, a foggy tendril of breath streaming from his mouth before dissipating as if never there. His name was Elias Ring, keeper of a boardinghouse in Manhattan, and the specter of death had continued to haunt him and his wife and everyone in his establishment even after the dawn of the hopeful new year, for one of his lodgers, who happened to be his wife’s cousin, a youthful beauty by the name of Gulielma Sands—Elma for short—had been missing since before Christmas, having gone out one snowy evening carrying a muff she had borrowed from another lodger and never returned. They had searched everywhere, and everyone feared the worst. Ring had even gone so far as to hire a man to drag the Hudson for her corpse. Now with the New Year had come a troubling clue: a boy had found the borrowed muff in Lispenard’s Meadow and it had been given away as a gift to someone who later happened to hear of Elma’s disappearance, and more specifically of the article she was said to be carrying.

Word having reached Elias, he marched out to the meadow and to the home of the boy who had found the muff. Within a short time, Elias, together with the boy’s father and several others, set out across the meadow to the place where the boy had discovered the muff, a disused and boarded up well. Called the Manhattan Well, it had been considered by Burr’s Manhattan Company as the source for the new water project but had been rejected in favor of a freshly dug well elsewhere. There it stood, a lonely, breathing hole in the earth, and one of the boards closing up its maw had been pried off. The deputation of searchers probed the well with poles, and making the grim discovery that there was indeed some heavy, sodden mass in the water below, they went about hooking it and hauling it up. Upon the task’s completion, what was struck by the daylight in turn struck the men with horror and repulsion: a sopping sheet of dark hair, the waterlogged material of a filthy dress, and in between, glimpses pallid, slick and stiff flesh.

Lispenard's Meadow, via The Lineup

It was Elma, Elias confirmed, and someone fetched a constable. The constable arrived to find a muttering crowd gathered round the body, and by their demands he felt compelled to act immediately, for it seemed that rumors had for some time already held a certain man in suspicion, and the discovery of Elma’s body meant, surely, that Levi Weeks, another lodger of Elias Ring’s and erstwhile companion of the deceased young lady, was guilty of her murder and must hang. The constable set out, the beginnings of a mob at his back, and found Weeks at the workshop where he plied his trade, performing carpentry for his brother Ezra Weeks, a prominent house-builder who had also helped to construct the new waterworks stretching from Lispenard’s Meadow into the city. The constable found Levi Weeks, a handsome and strong young man, rather less than surprised. He did not even need to be told what was happening but rather discerned it from the faces of those who came to him. And then, seemingly unprompted, he said something that would be held as the strongest piece of evidence against him: “Is it the Manhattan Well she was found in?”

*

Levi Weeks had both an alibi and a benefactor in his wealthy and influential brother, Ezra, for he had been at his brother’s house for dinner on the evening of Elma’s disappearance, and in order to help prove this, Ezra hired a team of the best attorneys in the city, one Brockholst Livingston and the powerhouse duo of Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, who agreed to put aside their personal and political enmities for the purposes of seeing justice done in this sensational case—as well as for the payday it promised. And it was indeed a question of whether justice would be done, for it appeared young Weeks was in danger of being railroaded.

Burr and Hamilton, via History.com

Rumors had begun to circulate well before the discovery of Elma’s corpse because Levi was known to be close with Elma, going out on the town with her occasionally and often speaking privately with her in her room. Indeed, many in the household anticipated an imminent wedding proposal, and although the two of them left the boardinghouse separately on the evening of Elma’s disappearance, ostensibly with different plans, Elias’s wife believed that she heard them whispering to each other on the stairs before leaving, likely making clandestine plans that would conclude with Elma’s bloody murder. And such talk was not only exchanged among those who knew Levi and Elma, but rather, the rumormongering had run amok through the city, with gossipers, or perhaps just one, spreading the tale that Levi’s guilt was a known fact, his hanging a foregone conclusion. Handbills had even been printed and circulated that talked of Elma’s ghost seeking retribution against her lover, and demons dancing about the lip of the well to celebrate the Devil’s victory in persuading Levi Weeks to commit his terrible act.

One newspaper piece, at least—this one likely penned by Aaron Burr himself—made the suggestion that Levi Weeks may be innocent of the crime and urged the public to suspend their judgment. This piece even went so far as to point out that Elma Sands may not have even been murdered, noting that she was prone to melancholy and idle threats of self-harm. This the Ring family disputed spiritedly in a statement of their own, though of course it must have occurred as a possibility to Elias Ring as he had paid to have the Hudson dragged in fear she’d drowned herself. Nevertheless, the Rings’ version of events was now a full-blown narrative, having been embellished through retelling to the point that Elma was now Levi’s fiancée, due to marry him the next day and likely already with child, and she had been murdered in her very bridal gown…quite a harrowing tale, though none of it be true.

The story did its job of whipping up the public fury, though, and while Levi Weeks languished in a jail cell, the Rings displayed Elma’s pale and ghostly corpse in their boardinghouse, opening their doors to any and all who wished to view this poor victim of brutality. And in an even more ghastly display, when it came time to carry her out of the house and bury her, they threw open her coffin and propped her up in the streets as an awful spectacle for the gathering crowds to see, making it clear all the while who they believed had taken her life. Such a deathly scene had not been observed in Manhattan since Washington’s funeral parade; this time, however, it excited feelings of outrage and vengeance rather than sorrow. And the very same crowds that thronged the street to see Elma’s body showed up at the courthouse on the first day of the trial of Levi Weeks, making a circus of what should have been a solemn and rational affair.

As the trial commenced, the prosecutor, Cadwallader Colden, took the floor to establish a motive for the alleged crime, calling on witness after witness to testify that Levi and Elma were not only courting but, as was generally believed, headed toward marriage. These witnesses, including Mrs. Ring with her claim to have heard the two conferring secretly upon the stair, were met with the form cross-examination of Alexander Hamilton, who frequently objected to their reliance on hearsay and challenged every bit of conjecture as immaterial and unreliable. Some witnesses, including Elias Ring and another lodger of his, even testified that some untoward intimacy may have developed between the two. Ring claimed that he heard some suggestive sounds from an empty room and the next morning found the bedclothes disturbed, and the lodger, a salesman named Richard Croucher who had a devilish aspect to his countenance, impugned Levi’s character in no uncertain terms, insinuating that he had even happened upon them in flagrante delicto.

Prosecutor Colden followed this testimony with that of witnesses who claimed to have seen Ezra Weeks’s sleigh on the night of Elma’s disappearance, flying through the streets on some secret errand, its bells removed to silence its passage. Juxtaposing this testimony with that of other witnesses who had seen a sleigh with a woman and one or two men in it, and others still who claimed to have seen a sleigh on its way out to Lispenard’s Meadow and to have witnessed footprints and sleigh tracks in the snow near Manhattan Well, Colden created a fabric of evidence meant to be taken together to indicate that Levi Weeks, and perhaps Ezra Weeks as well, took Elma on a silent sleigh ride to her deep and watery doom. Of course, Hamilton did not let this pass unchallenged and indeed was able to shred much of the testimony, forcing witnesses to admit they couldn’t actually discern the color of the sleigh’s horse in the darkness, or that they didn’t actually know what Ezra Weeks’s sleigh looked like in order to recognize it, or that they weren’t even certain when they saw what they saw.

Detail of 19th century painting depicting a horse-drawn sleigh in the countryside, via Wikimedia Commons

Finally, as a decisive thrust, Colden called multiple medical experts who gave the opinion that there were signs on the corpse that indicated she had been murdered. One doctor noted bruising on the neck and bosom and a telltale clicking when he pressed on the clavicle that indicated she had been strangled with such violence that her collarbone had snapped. This, of course, provided no direct connection to Levi Weeks whatsoever, but speculation that this indicated a crime of passion certainly made the assertion that the prosecutor wanted to make. And the speculative and circumstantial nature of the evidence isn’t even what the defense seized on in cross-examination, for there was something even more dubious about these experts. One wasn’t even a surgeon as he presented himself but was actually a mere dentist, and none of them had been among the doctors who performed Elma’s autopsy nor had even been present at the inquest. They had only had opportunity to examine the corpse while it was on display at the Ring Boardinghouse and in the streets of Manhattan, long after its removal from the well and after it had been handled by innumerable people.

In the prosecution’s closing arguments, Cadwallader Colden held forth on a certain legal text that insisted on the importance, nay, the indispensability, of circumstantial evidence in a murder trial, when the only people who knew with certainty what happened were either dead or guilty and thus not likely disposed to offer truthful testimony. An interesting philosophy, certainly, and Aaron Burr, rising to offer the defense’s opening arguments, promptly offered a sound rebuttal, pointing out that Colden had taken his quoted passage out of context, and that the legal text used by the prosecution actually argued against his point. Indeed, circumstantial evidence should not be relied upon exclusively when other evidence is lacking, as it might lead to innocent men being convicted on no more proof than coincidence and supposition.

The defense went on to call numerous witnesses able to confirm Levi’s alibi. He had come to his brother’s house for dinner, neither had taken the sleigh out for a late night ride in huggermugger, and Levi had left at so late an hour that, despite Cadwallader Colden’s claims to the contrary, he simply wouldn’t have had time to commit the crime before he was known to have returned to the Ring boardinghouse and retired for the night. It simply couldn’t have been done. And not only did Levi’s brother testify to the same, but he also gave a compelling reason why Levi might have asked whether Elma had been found in a certain well—it was the simple and obvious reason that word had already spread of the search for Elma taking place out on Lispenard’s Meadow, and Ezra himself, having some knowledge of the meadow in his capacity as the builder of the waterworks there, had mentioned to Levi that they were searching in the vicinity of the Manhattan Well.

Like the prosecution, the defense also called medical experts, only theirs were the actual doctors who had examined the corpse at the time of its discovery, at the coroner’s inquest. They disputed the conclusions of the prosecution’s experts, stating that no such indications of violence had been present at the autopsy, and furthermore, in contradiction of the fervent assertions of Levi Weeks’s accusers, they had found that Elma Sands had not been pregnant at the time of her death. Indeed, beyond some scratches on the hands, which may have been occasioned during her fall down the well whether she was dead or alive upon entering, there were no indications that she had been murdered, and there was enough water in her lungs to indicate she had died by drowning. It seemed the finding of the coroner that she had been murdered was more a result of social pressure than of any scientific deduction, and the presiding physicians were rather more of the opinion that she had killed herself by leaping into the well. Thus the defense was justified in following other avenues of inquiry not supportive of homicide, raising such evidence as Elma’s melancholy, her habitual use of laudanum and offhand threats of suicide.

But they had already suggested these notions to the jury in cross-examination, and since many jurors likely still believed she had been murdered, it seemed more important instead to cast a shadow of doubt on the prosecutor’s narrative of Levi’s guilt. And this they did by raising other suspects for the court to consider, the first being none other than the Quaker keeper of the boardinghouse himself, Elias Ring. This they accomplished by turning against him his own story of secret rendezvous scandalously overheard, for it turned out that the neighboring building, a blacksmithery, shared a wall with the boardinghouse, and the blacksmith had actually heard carnal encounters taking place in Elma’s room. This neighbor swore that he had heard the voice of Elias Ring himself having trysts with Elma Sand while his wife was away during the height of the Yellow Fever, and even remembered remarking upon it to his wife, to the effect that he feared Ring had ruined the poor girl. Therefore, it appeared that Ring was the cad misusing the girl, not Levi.

A drawing sometimes used as a depiction of the Ring Boardinghouse, via Murder by Gaslight

Then there was the other tenant of the boardinghouse, Richard Croucher, who had been only too happy to testify that he had seen Levi and Elma in a compromising position, he whose diabolical features already made the jury and the crowd disposed to distrust him. Croucher admitted that he had somehow offended Elma in passing her through a hallway, perhaps by brushing against her or by some more impertinent act, and that he had almost come to blows with Levi, who had defended her honor in the matter. So it seemed Croucher had some basis for resenting the both of them, and as it turned out, over the course of various witness testimonies, it had been Croucher who had so industriously spread the rumor that Levi was guilty of murdering Elma. Throughout the time that Elma’s corpse stood on display in the boardinghouse, he was seen haunting the room, telling anyone who might listen that she had been done in by her lover, Levi Weeks. And witness after witness confirmed that Croucher had gone about bursting into stores and taverns, shouting the news of Levi’s guilt. Once, when a grocer gave similar testimony about a stranger coming into his establishment not to purchase anything but rather only to spread his poison against Weeks, Alexander Hamilton lifted a candle to better illuminate Richard Croucher’s face in the dark courtroom so that the grocer could identify him. Moreover, it was revealed that the blacksmith neighbor had actually confided his secret about Elias Ring’s infidelity with Elma Sands to Richard Croucher. The fact that Croucher would spread rumors and swear evidence against Levi Weeks yet omit this important fact absolutely compromised his credibility, and the notion that he might have actually used this knowledge to blackmail Elias Ring into helping him pin the crime on poor Levi Weeks tended also to cast suspicion on him as being the actual killer.

By this time, the trial had stretched on for days, such that the judge had been forced to sequester the jury by having them sleep on the floor in the courthouse on the first night, and late on the second day, everyone was exhausted. Hamilton and Burr had weakened the prosecution’s case and made a strong defense, and so, confident in their work, they closed their case without any closing argument. The jury retired… and returned very shortly, after almost no deliberation, with a verdict of not guilty, which was met by the resounding cheers of a crowd that two days before would have lynched Levi Weeks in the streets if they’d had their way.

Today, the murder of Elma Sands remains unsolved. Did she kill herself? Did Levi kill her? Or was there a murderer on the loose? The people of New York, at least, were satisfied some months later that the perpetrator was identified when Richard Croucher, the nefarious looking fellow lodger who had so besmirched Levi Weeks’s name, was arrested and tried for rape. According to the details that emerged in his subsequent trial, after his recent marriage, he took his young stepdaughter to the Ring boardinghouse to help him pack his things, and it was there that he forced himself upon her most brutally. In doing so, he even raised the topic of Elma Sands, threatening that he would kill this girl the same way Elma had been killed if she told anyone of what he’d done to her. It was not exactly an admission of guilt in Elma’s murder, but for many, it was close enough. And in Paul Collins’s fantastic book Duel with the Devil, which I have relied on as my principal source for this episode, Collins relates some unsettling details about his history that further depict him as a man capable of murder. In England, he seems to have had a psychotic break and attempted to slay someone, an act that earned him the nickname Mad Croucher. And after his release from prison in New York, having served his time for the rape and been pardoned on the understanding that would leave the country, he instead went to Virginia, where he was eventually arrested for theft. Finally forced to return to his native London, we have a final report, recorded by a son of Alexander Hamilton, that he was ultimately put to death for some “heinous crime.”

Yet in popular imagination, many overlook this likely suspect and instead have suggested that Burr and Hamilton helped exonerate a guilty man. This can be largely attributed to the myths and folklore that have arisen around the case. First, ghosts have ever surrounded the affair. After the handbills about goblins and spirits in Lispenard’s Meadow, there arose a variety of stories about the Manhattan Well being haunted by the restless spirit of Elma Sands, such that one can imagine her crawling out of its depths, wet and pale, like a scene straight out of The Ring.

Indeed, these ghost stories persist even today and seem to imply that justice was not done 217 years ago, even though nearly everyone at the time seems to have been satisfied with the verdict. The trial has been compared to the OJ trial because of its sensational aspects and the “dream team” assembled in Weeks’s defense, but in this regard it was different. Unlike the OJ case, the public was relieved that they hadn’t convicted what appeared to be an innocent man.

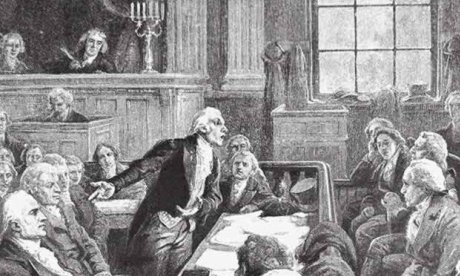

Even those who weren’t at the trial soon learned all about it from some popular narrative accounts of the proceedings that were widely read, as this was the first well documented court case in our history, and with popular versions of the events written by a variety of spectators as well as the court reporter, it might be considered one of the first popular publications in the modern True Crime genre. It was because of this popularity that it soon became exaggerated in memory and mythologized. One example of this corruption of the record is the moment when Hamilton held up a candle to identify Croucher; this has become a cinematic scene in the popular imagination, and has even been illustrated as such, in which Hamilton (or Burr, depending on the account) lifted two entire candelabras and dramatically thrust them forth in a pivotal courtroom moment, to identify the true murderer.

Depiction of exaggerated events at the Weeks Trial, via the Library of Congress

Another example derives from a novel about the trial written anonymously some 70 years after the affair by a granddaughter of the Rings. This book concocted a scene in which Mrs. Ring waited outside the courtroom to curse Burr and Hamilton for using their wiles to free her cousin’s murderer, a myth that has proven very popular in the telling of this tale, supported as it is by the unhappy fates of some involved in the trial, such as the judge, John Lansing, who some years later disappeared never to be seen again. And of course, the most commonly raised proof of the existence of Mrs. Ring’s curse, the ensuing woes of the two most prominent historical figures in the narrative, starting with their fateful duel and, at least for Burr, continuing on to further hardships and miseries, some of which I’ll be discussing in the upcoming Blind Spot. For now it is enough to remark upon the historical blindness that occurs when mysteries such as these go unsolved and when facts and truth become cluttered with embellishments and folklore.

*

Thanks for listening to Historical Blindness, the Odd Past Podcast. Aside from the few sources to which I’ve linked in the body of the blog post, I relied almost entirely on Paul Collins’s amazingly well-researched book, Duel with the Devil: The True Story of How Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr Teamed up to Take on America’s First Sensational Murder Mystery. If you’d like to read this book and support the podcast at the same time, please visit historicalblindness.com/books, where I’ve set up a reading list with great books for further reading on the topics of every episode I’ve ever done!